Going round in circles: How Leeds kept taking wrong turns with its big ideas for urban transport

The year was 1988 and, in Leeds, plans had been announced for a light rail network linking Seacroft and Cross Gates with the city centre.

That scheme was soon scuppered by local political in-fighting and, nearly three decades later, Yorkshire’s biggest city is still waiting for the long-promised transport revolution that will ease the strain on its traffic-choked roads and help it maintain its position as one of the UK’s regional heavyweights.

BACKGROUND:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

For many years, Leeds pinned its hopes on the kind of tram system that is today operating in places such as Sheffield, Manchester and Nottingham.

Proposals for a £100m Leeds Supertram that would run between Middleton and the heart of the city were unveiled in 1991 but government funding remained frustratingly elusive over the rest of the decade.

Come 2001, however, and all that changed, with John Prescott giving the go-ahead to a scheme that was now expected to cost £500m.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBids to build Supertram were lodged by rival consortia and advance work even got under way on the A61 Hunslet Road.

It appeared to be all systems go – until the revelation in late 2003 that the city was locked in crisis talks with the Department for Transport (DfT) over an estimated price tag that had spiralled to nearly £1bn.

The transport secretary of the time, Alistair Darling, confirmed in November 2005 that he would not be funding Supertram, despite around £40m having already been ploughed into the scheme. From there it was back to the drawing board, with Mr Darling assuring Leeds he was keen to still provide cash for a state-of-the-art bus system.

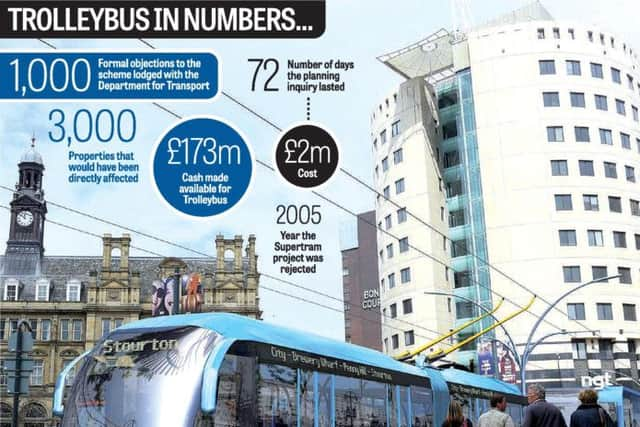

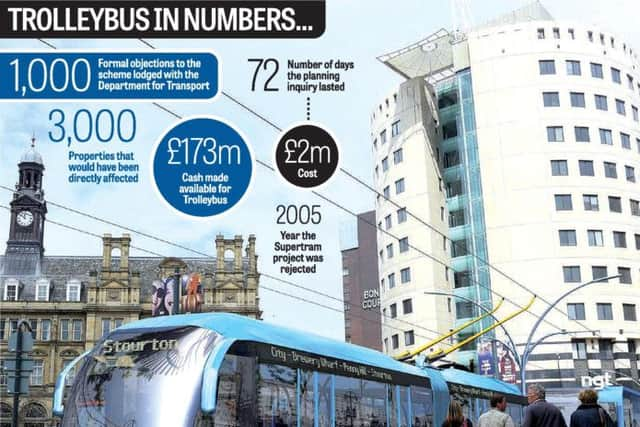

The replacement project the city eventually settled upon was New Generation Transport (NGT), better known as trolleybus.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPowered electrically by overhead wires, it was slated to serve destinations including Lawnswood to the north and Stourton to the south of the city.

By 2009, hopes were high that trolleybus would win approval following the submission of a formal business case to the DfT.

The then Labour government duly made provisional funding available in March the following year – but this proved to be another false dawn. Out went Labour in 2010’s election and in came a coalition government that placed major spending commitments such as NGT under review.

Two years of delays ensued before Nick Clegg arrived in Leeds in July 2012 and gave the green light to the £250m scheme, saying: “What we are doing is something that Labour failed to do for 13 years.” Just under £175m was set aside by the DfT, with a further £77m due to come from Leeds City Council and Metro, West Yorkshire’s passenger transport authority.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLeeds, though, still needed formal permission to build and operate the system, permission that could only be granted after a public inquiry. It took place over the course of 72 days in 2014 and heard claims from objectors that trolleybus would damage the environment and offer poor value for money.

NGT’s promoters – the council and the West Yorkshire Combined Authority, which includes what was Metro – insisted it would create up to 4,000 new jobs and generate an annual £175m for the economy.

But with yesterday’s announcement, it became clear that the objectors, rather than the city’s civic leaders, had won the argument.