Grimethorpe: Rescued from the pit of despair

The village of Grimethorpe, on a cul-de-sac seven miles out of Barnsley, came to symbolise Yorkshire’s mining industry in its death throes. Perhaps it was the name; perhaps the fact that they filmed the movie Brassed Off there.

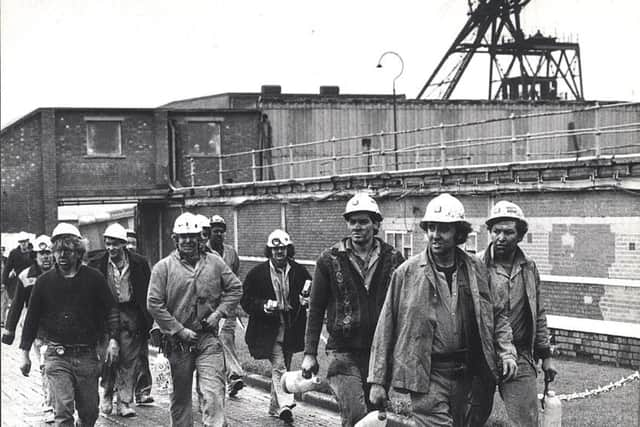

It is 25 years this week since the pit closed. Some 6,000 people still worked there and at the merged Houghton Main and Dearne Valley collieries. In a community in which 44 per cent listed their occupation as “miner”, it looked like a fatal blow – and within a year, Grimethorpe had been named Britain’s poorest village, by the EU.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It really was a coal mining community in every sense of the word,” says Sir Stephen Houghton, a former colliery worker down the road at Shafton, who helped lead the regeneration effort and who now heads Barnsley Council.

“The Coal Board owned the houses and provided the leisure facilities in the village, training and jobs. So when the pit went, the whole infrastructure went with it and the village went into freefall,

“We actually debated at the time whether we should literally bulldoze the village, grass it over and forget about it. That’s how big the impact was.”

But a generation on, Grimethorpe has survived. Much has changed and a great deal for the better – yet it remains a challenged community.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The council thought everyone would leave, do a flit, when the pit went. Where they thought everyone would go I don’t know,” says Danny Gillespie, who spent 36 years at the colliery and four on the council.

“I used to work there seven days a week, for the overtime,” he laments. “But at the end of the day I was just a number. Just a bit of summat and then thrown away.

“I was in shock for two years. What was I going to do? What would happen to us?”

He drives through the former Coal Board estate where he lives, pointing out the houses. “Druggie, druggie, druggie,” he reels off.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I’ve got four drug houses right across the road from me, and you get to a stage when you think, enough’s enough. I used to know everyone on this street. Now I know maybe three or four people.”

It is a sentiment that sums up the new Grimethorpe. It used to be a coal community; now it’s a collection of estates, some nice, some less so, which could be anywhere in the North of England.

The village hub, where May Day parades were once staged and which served as a social centre, is abandoned grassland now – its place taken, after a fashion, by the Asda supermarket down the road.

A few hundred yards away, the former vicarage and one-time community centre is burned out and awaiting demolition.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We’ve got lawyers, police, all sorts, living here now,” says Mr Gillespie. “But they haven’t connected with the rest of the village.”

Grimethorpe also has its share of less desirable occupants.

“We’ve got families who have never worked, never will work, whose kids will never work and who don’t give a monkeys. If the pit was open they still wouldn’t be working,” Mr Gillespie says.

Elsie Smith, who helped set up Grimethorpe’s model Neighbourhood Watch community, agrees that unwillingness to work, rather than the lack of available opportunities, has contributed to the area’s malaise.

“We’ve always had families like that here – even when the pit was open,” she says. “One woman moved here from the south and she couldn’t understand why the kids weren’t looking after the parks we have, They didn’t have parks at all where she’d come from.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“She appreciated what we’ve got here. Of course, she was able to buy a house cheap – that’s why she came.”

Mrs Smith, whose late husband, Brian, had been a miner and a horn soloist with Grimethorpe’s famous Colliery Band, agrees that the new estates have changed the village, but not always for the better.

“You can see which ones are social housing,” she says. “You can pick ’em out.”

The village’s housing stock is unrecognisable from that of 25 years ago, as it its landscape. Its first private estates went up a decade and a half ago, at around the same time as the last traces of the pit began to vanish.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFew would know that the land alongside the new link road to the industrial estates which now provide some work for the locals, were once the spoil heaps.

They didn’t dismantle the pit; they blew it up. Millions of pounds worth of German coal-cutting machinery remains forever beneath the Tarmac.

The road and the vast, barn-like workplaces are the fruits of unprecedented investment in the area. Around £164m of public and private money is estimated to have been pumped into the village. A lot of the public cash came from Europe – an irony given the 70 per cent pro-Brexit vote across the Barnsley district.

“It was Europe that stopped Grimethorpe from going under,” says Coun Houghton.

Even so, the money did not buy a quick fix.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“People shouldn’t underestimate what’s been achieved. We had to completely rebuild the community from scratch,” the council leader adds.

“The deprivation was far worse 15 years ago than it is now. That’s not to underplay the problems Grimethorpe still has, as have a lot of other places.”

Mr Gillespie, who served as an independent councillor in Barnsley, notes that a good deal of the private stock remains in the hands of absentee landlords.

“A lot are still boarded up and trashed,” he says. “There’s 9,000 kids in some of these houses. They were beautiful homes. Now look at ‘em.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJobs, too, remain a bone of contention – the online fashion retailer Asos, whose distribution plant occupies one of the new warehouses, is the antithesis of the unionised pit culture it replaced. Last year, six local MPs paid it a visit after reports that its workers often went without regular toilet or water breaks.

The company said the claims were inaccurate.

“There are now the big employers which the area needs but the economy has changed,” says Coun Houghton. “It isn’t skilled and well-paid work now – it tends to be minimum wage jobs.”

Yet nostalgia for the better times and for the village they had known has not left Grimethorpe’s older residents hankering for the past.

“My husband suffered with his chest and died at 69,” says Mrs Smith. “Do you want that kind of life for your kids?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“One of my boys is a biochemist now. If the pit had been here, he’d have gone down it. That’s the kind of institution it was.

“I don’t miss it.”

• The death knell for the pit at Grimethorpe had followed Michael Heseltine’s announcement in 1992 that up to 31 of the country’s 50 remaining deep mines would have to go. Some 31,000 would be jobless.

The village had already seen hard times – the miners’ strike of 1984 made paupers of many of its residents. “We lived on bits of cheap meat and anything we could scrounge,” says Mr Gillespie. “I used to be on the coal steps, riddling coal and pinching it and flogging it to keep warm,”

Mrs Smith remembers: “We got £7.23 a week to live on. We were wiped out.”

The village suffered a further blow in 2013 when the clerk of its parish council went to jail for a fraud that left it £1.3m in debt.