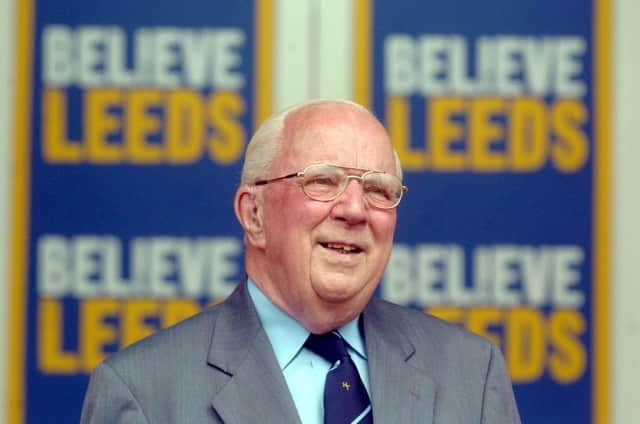

Harry Jepson remembered: Appreciation of rugby league legend

But don’t try looking for a replacement bulb, they don’t make them like that any more.

Harry Jepson was a gentleman in both senses of the word; a gentle man and one of the true gentlemen of the 13-a-side code he so adored; always immaculately turned out, representing and advocating the sport wherever he went.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the later years of a distinguished, varied and unmatched administrative career – for which he received the OBE for his services to the game – he used to frequently say when asked his thoughts on the state of the game, “there’s nothing worse than an ex”.

Yet he was never anything less than contemporary in his regard of, outlook on and everlasting passion for league.

And right up to his passing, aged 96, ironically and aptly on the 121st birthday of rugby league on Monday, August 29, so many sought his sage advice, valued opinion and revelled in his company.

Rugby league has also lost one of its finest raconteurs.

Harry’s recall of the characters he met – from the initial Hunslet heroes he used to travel to games with on the tram, including Gracie Fields during the Second World War, to world-renowned writer Thomas Keneally – was as exemplary as it was entertaining.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis memory for matches and the key incidents in them, painting glorious verbal pictures for an agog audience, was unsurpassed and his razor-sharp memory was immaculate to the last.

He could be ruthless when needed, as a deputy headmaster who prided himself on earned respect, manners and discipline; when a member of the inaugural Rugby Football League board of directors in the mid-1980s, and when taking over the running of Paris in their second, and last, season in Super League in 1997, but he never lost the common touch.

His always-twinkling eyes beguiled and left a never-to-be-forgotten impression on everyone he came in contact with.

Last year, travelling down to the Challenge Cup final at Wembley, regaling with joyous stories throughout the journey as usual, we stopped at Leicester Forest East services.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs soon as he got out the car and began to make the short journey through the queues of fans, Harry was mobbed, with ex-pupils, former rugby players and friends he had made in the game wanting to hug, kiss or shake his hand in gratitude for the opportunities he’d given them.

Once met, never forgotten.

Of all the accolades he received, the one that gave him the most satisfaction was to have the Grand Final trophy in what was initially the Rugby League Conference named after him, currently held by South West London Sharks.

Formalised in 1998, the summer competition for community clubs in development areas has been staged across England.

However, no matter the tyranny of distance in his later years, Harry never missed one.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe revelled in those days meeting fellow stalwarts and evangelists, and in going back to hosting rugby union grounds that had previously, in a different era, thrown him out for being a league ‘spy’.

He loved the idea of spreading the word about something that had given him so much joy and, as a result, was always an expansionist.

As a schoolboy at Cockburn High in 1934, where he excelled in learning French, when the first players came across the Channel to learn the game from Joe Thompson at Headingley, Harry skipped class and asked the great Jean Galia for his autograph in his native tongue.

It spawned not only a love affair with French rugby league, he regularly travelled there, and was treated like royalty.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is somehow fitting that Hunslet play Toulouse this afternoon.

Born in Hunslet in 1920, Harry saw his first game seven years later when his uncle took him to Parkside to see the myrtle and flame play Featherstone in a match that saw the debut of his first hero, Jack Walkington.

“I couldn’t believe that the players performing these wonderful feats of athleticism were the same people who worked in local factories,” Harry said of receiving that imbuing spirit. “Ordinary working men who wore overalls in the street were transformed into giants on a rugby field on Saturday afternoons.”

He never lost that sense of awe.

An avid reader, and historian of and for the game, his passing severs the last direct link with the meeting at the George Hotel, Huddersfield, that formed the Northern Union, as was, in 1895.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn his youth he met such as Albert Goldthorpe and Joe Lewthwaite who had attended that breakaway.

Harry claimed that his life was altered by a random act from a Leeds council official when he was demobbed after serving in the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment and then the Royal Army Service Corps during the Second World War, seeing active duty in North Africa and southern Italy.

Trained as a school teacher on his return, he was seconded to Bewerley Street School where he fortuitously came under the wing of the headmaster there, Edgar Meeks, the Hunslet chairman.

Starting as assistant secretary at the club, he left when Parkside was heartbreakingly sold, being staunchly against it and, in the early 1970s, moved across to Leeds where one of his proudest achievements was the setting up and becoming chairman of the Colts League, the precursor to today’s academies.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe managed the inaugural GB Colts tour to Papua New Guinea and Australia, further enhancing his particular affinity with and for Queensland.

From football chairman to president of Leeds – and chairing the RL council meeting that brought in Super League in 1995 – last year he revelled in seeing the Rhinos do the treble claiming that it was “without doubt, the finest team that he had seen” – there could be no finer accolade.

His last public appearance was a month ago when he was awarded an honorary doctorate of education by Leeds Beckett University.

After making a captivating speech of thanks, the room rose en masse to give him a standing ovation, university officials astounded as it was the only time that has happened.

Such was the all-encompassing bonhomie, drawing power and humanity of Harry Jepson.

Phil Caplan, rugby league writer who is also co-director of Scratching Shed Publishing and Forty-20 magazine.