How Dr Beeching’s axe signalled half a century of change on Britain’s rails

Wednesday, March 27,1963 was not a good day for me. As far as I can recall it was double physics followed by PE, but out of the corner of my eye I kept a lookout for the daily train of coal empties that used to struggle up the track from a nearby gas works.

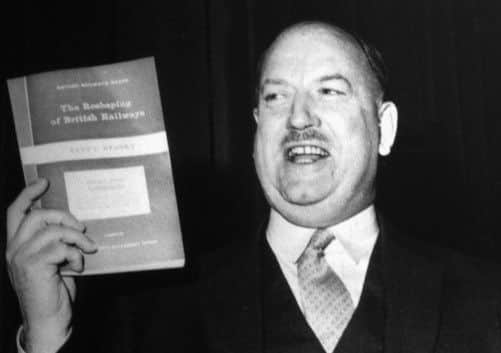

On the same day 100 or so miles away to the east, the chairman of the British Railways Board, Dr Richard Beeching, was giving a news conference in the Charing Cross Hotel on the publication that day of his report on the future of Britain’s railways. It was entitled The Reshaping of British Railways and it was available from Her Majesty’s Stationery Office for the princely sum of one shilling (5p).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBeeching was about to become a household name and his decision to close thousands of miles of railway track would by the end of the day be known as the Beeching Axe and, in the years that passed, his recommendations would be blamed for all manner of social and economic ills.

The closure of uneconomic railway lines was not a new phenomenon and had been gathering pace since 1948 when the post-war rundown railways were nationalised – around 3,000 miles had already been closed by the time of the Beeching Report and there was certainly a persuasive case for change.

The 1955 “Modernisation and Re-equipment of British Railways” was a worthy attempt to bring Britain’s railways into the 20th-century, but its implementation left a lot to be desired.

Untried and unreliable diesels were hurriedly introduced while modern and efficient steam locomotives, sometimes no more than five years old, were being sent to the scrapheap.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOf course, Britain’s railways had been a steady drain on the taxpayer since nationalisation in 1948 – but so had the armed forces, the police and the NHS. There are some organisations which we don’t or at least didn’t expect to make a profit, or break even. The railways were somehow different. The figures didn’t add up and there was only one way to balance the books. Cuts.

Certainly, the steady drip, drip of passengers and freight to road transport coupled with a worn out system, out-of-date working practices, over-manning and strikes was threatening to cripple the network. By 1961 British Railways was operating on an annual deficit of £87m-£1.65bn in today’s money. The then Tory Government decided to call time on these ever-increasing losses from the public purse – enter Dr Beeching.

In 1960 Dr Richard Beeching, then Technical Director at ICI, had been appointed by the then Minister of Transport, Ernest Marples, to the Stedeford Committee which was set up to look into modern management practices for the railways.

So impressed was Marples with Beeching’s ideas about drastically pruning the railway network that he asked him, unsurprisingly, in 1961 to join the British Transport Commission as chairman designate of the new British Railways Board – his brief was to “reshape” Britain’s railway system.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBeeching became chairman of British Railways at the beginning of 1963 and within three months his infamous report had been published. Drastic surgery was not far away – in fact some lines listed for closure in the Report had already been closed before its publication.

The two-part Beeching Report, as it became known was made up of 148 pages of statistics, a 42-page appendix and 13 fold-out maps, but by and large the public weren’t concerned with the detail.

What they wanted to know were the headline figures which were splashed across the newspapers the following day. In short the report recommended the closure of around 5,000 route miles of railway and the closing of over a third of the stations.

Hidden away on page ten of part one of the report was the staggering piece of information that all of the statistics used in the report were gathered from a survey that took place in just one week, April 17-23 1961. According to these figures a third of the route mileage carried only one per cent of passenger and freight traffic. And thus was the fate of our railways sealed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Hull to York line via Beverley was one of those held up as evidence of the need for change. Nine trains ran in each direction on weekdays and they carried an average of 57 carriages. By closing five of the stations along the route the report predicted £69,700 would be lost in gross revenue, but £81,000 would be saved in running costs.

While those who lost their stations took Beeching’s name in vain, he was not without support. Having closely studied the report, an editorial in the Yorkshire Post followed the next day.

While stopping short of giving Dr Beeching a standing ovation, it read: “The accountants have moved in where to judge by the admitted uncertainty of many of the report’s statistics they have feared to tread for many years...The report spikes all the critics’ guns. It is no use saying, ‘500 people use this line every day’...Dr Beeching can prove that 500 people is not enough. He does this by deducting from the takings of the line, the movement expense.

“Provided that this plan is taken as a starting point for a national transport policy and not as the signal for a frenzy of uncoordinated activity it will prove a memorable advance in British social history.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNot everyone shared that view, with Lord Stonham, chair of the National Council for Inland Transport accusing Beeching of dragging the country backwards. “Far from gearing the railways to the needs of the 1960s,” he said. “It will in some ways reduce public transport to a lower level than in the horse age.”

Calls for caution were ignored and with motorway-loving Ernest Marples as Conservative Minister of Transport, the destruction of Britain’s railways moved into top gear. A change of Government on October 16, 1964 saw no end to the slaughter, especially in rural areas, even though the Labour Party had previously pledged to halt the closures if elected – you just can’t trust politicians – although to be fair there were a few reprieves under Labour’s Barbara Castle, with lines like Huddersfield to Penistone and Harrogate to York spared the chop. Nevertheless, Yorkshire was particularly hard-hit. By November 1965, 13 lines in the county had closed.

By August 1968 standard gauge steam traction had been eradicated from British Railways and another 3,500 route miles had been closed. Closures, albeit at a much slower rate, continued until the mid-1970s when the system stabilised to more or less what exists today. In total around 4,500 route miles, 2,500 stations and 67,700 jobs were all lost. In more recent, enlightened times, with gridlock imminent on Britain’s road network, a few of these closed railways have been reopened but we will never be able to regain all that was lost in the frenzied destruction following the Beeching Report. What is even more maddening is that today’s so-called “privatised” railways cost the taxpayer much more in real terms than poor old BR did in 1963.

“In time the railway historian will probably look at the closure of our railways with his cool analytical eye and decide it is all part of a progressive social pattern,” says the narrator on footage in the Yorkshire Film Archive. Recorded the day after the cuts it shows a diesel locomotive pulling out of Whitby, while a man on a platform reads the local newspaper. The headline is “Beeching axe to fall on Whitby railways”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe narrator continues: “In the 1840s, no landscape painting was complete without its railway in the foreground. A similar scene today will probably show the scar of some abandoned railway which in time will be hidden by the dead weeds of winter or the ever creeping flowers of summer, in some measure a floral tribute to the passing of yet another chapter in railway history.”

Dr Beeching’s Axe 50 Years On by Julian Holland is published by David & Charles, priced £18.99 on February 23. To pre order a copy from the Yorkshire Post Bookshop call 01748 821122.

Not quite the end of the line

While dozens of stations were axed and thousands of miles of track lost, some lines managed to rise from the ashes.

The line between Whitby and Pickering was one of those that fell victim to Dr Richard Beeching’s infamous cutbacks, closing in 1965. However, thanks to the dedication of a group of rail enthusiasts, it reopened again in 1973.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNow, carrying more than 350,000 passengers a year the line, originally planned by George Stephenson to improve trade from the coast, lays claim to being the world’s most popular heritage route as the North Yorkshire Moors Railway. Celebrating its 40th anniversary next month, it brings in more than £30m a year to the local economy and has been an undoubted success story.