Libraries turn back pages of the past

The first thing you notice is the computers. Two dozen of them, with people gazing intently at the screens and more people waiting in a queue to take over when they’ve finished. The hush in the computer and internet centre at Sheffield’s Central Library is disturbed only by the pitter-patter of the keyboards.

The library, an august white 1930s building, has changed a lot since the 1960s when, as a lad in a school cap, I came every Saturday morning to browse the shelves, flick through the cuticle-shredding card indexes, and pile up my books to be stamped at the counter. Whole armfuls, from The True Book of Dinosaurs, through Jennings and Bunter, to HG Wells, Jules Verne and Great Expectations (which we grammar school kids most certainly had).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was a world that’s been explored in a Sheffield project to be featured as part of next Saturday’s National Libraries Day, an annual event which aims to “celebrate the value of libraries, librarians and information professionals”.

I’m not sure we would have understood what “information professionals” did (much less how valuable they were) back in the 60s. But then, we wouldn’t have expected libraries to – as many do now – serve coffee, restyle themselves as community centres and have sections called life skills, parenting, healthy lifestyle, alternative therapies and gay and lesbian collection.

Libraries reflect the society they serve and, in these cash-strapped, internet-dominated times, they are having to redefine their relevance. They are, after all, an all-too-easy target for council funding cuts. Sheffield’s annual libraries budget, for instance, is due to be reduced from £6.4m to £4.8m, with up to 14 of the city’s 27 community libraries facing closure.

How different things were in the 40s, 50s and 60s, the decades covered by community historian Dr Mary Grover in the Reading Sheffield oral history project, which she will be discussing in a Central Library talk next Saturday afternoon, which will also include a rare public screening of a period-piece Yorkshire film.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMary, a former lecturer at Sheffield Hallam University, is a specialist in 20th century popular fiction and has set up an archive of it at the university. It boasts the sort of novels which literary snobs (and some librarians) have traditionally sneered at: Grand Hotel, The Scarlet Pimpernel, Lost Horizon,Tarzan of the Apes, No Orchids for Miss Blandish, books by CS Forester, John Galsworthy, Gilbert Frankau, Mazo de la Roche, Howard Spring and (a major Grover enthusiasm) Warwick Deeping.

“A huge number of academics and journalists make assumptions about why people read popular fiction,” she says. “But there are very few studies actually asking people what they read and why.”

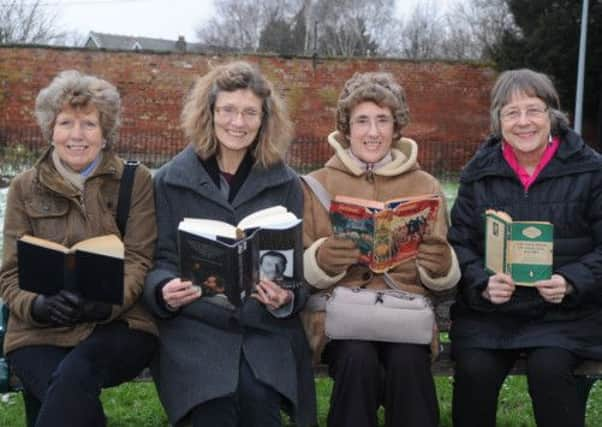

Mary and a team of 12 interviewers have talked to more than 50 people, mostly over retirement age, about their reading lives and how, as she says, “the libraries were absolutely key to most of them, not just for pleasure but for giving them access to education, to a world elsewhere.” Some were recruited through library reading groups, others through elderly people’s lunch clubs and the Sheffield Home Library Service, whose work includes delivering books to housebound people.

The interviews make fascinating reading in themselves. There’s Shirley Ellins, a former teacher, recalling reading John Buchan, Arthur Ransome, Thomas Hardy, Greek myths and Conan Doyle’s historical novels. “I got chicken pox as a girl and I read the whole of Jane Austen, one after the other, to take my mind off the itching,” she says. And she remembers acting out Shakespeare “with the book in one hand and a ruler serving as a sword”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdKen Mayes, who worked as a draughtsman, recalls his local library opening when he was 10 and keen on adventure stories. “The very first book I got was the thickest one I could find, called The Great Aeroplane Mystery. Absolute rubbish, of course, but it was a thick book.” He gradually moved on to Marx’s Das Kapital: “I used to sit up in bed, ploughing my way through it.”

Former headmaster Malcolm Mercer tells how he took a copy of the poetry anthology Palgrave’s Golden Treasury with him when he joined the Navy in the Second World War. He kept a notebook about everything he read between 1940 and 1942 – under “D” his list included Dickens, Dostoyevsky and Warwick Deeping. And steelworker Jim Green recalls reading Orwell’s The Road to Wigan Pier when he was 15 or 16. “It really opened my eyes,” he says. “We were living as he was describing. And the first dawnings in my mind were: ‘This ain’t right; we shouldn’t be living like this and we’ve no need to live like this.’”

Mary Grover is interested in how, before book-buying edged out book-borrowing, people became readers, how they discovered books, chose what to read and developed tastes that may now seem startlingly catholic, adding: “There was a huge serendipity about it for most of the 20th-century. Now you tend to imagine people sitting in front of a screen and ordering books on Amazon. With the internet, we may read to reinforce our tastes, whereas in the 1940s it was more exploratory, which led to a greater sense of curiosity. The most popular book among our readers was Anne of Green Gables – about the way education transforms an orphan.”

With information, as well as books, now available at the click of a mouse, it’s enlightening to discover how scattered Victorian public libraries could be. “If you lived in Chesterfield in the 1870s and you wanted to find out about something, you had to get the train to Sheffield,” says Mary.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs well as public libraries, there were commercial libraries, like the Red Circle chain with its slogan: “Reading: Your Cheapest Pleasure”. “They stocked romance in huge quantities, detective stories, cowboy books, horse-racing fiction,” says Mary. “One of the people we interviewed was sent by her father to get his ‘betting books’ as she called his racing books.”

Mary’s talk will include a screening of Books in Hand, an upbeat 1956 promotional film about Sheffield’s libraries. Astonishingly, the film (part of which can be viewed on the Yorkshire Film Archive website: www.yorkshirefilmarchive.com) was shown on television more than 200 times. A copy was held in the Lenin State Library in Moscow, and it was sold to Australia, Italy, India, Liberia, Malaya, Yugoslavia and Portugal. Quite what people in Malaya made of its glimpses of suburban Sheffield is hard to gauge.

“Do you know that over 500m books are issued every year?” asks an avuncular voice on the soundtrack. “But all it costs every citizen each year is the price of a few cigarettes.” The film goes behind the scenes at the Central Library, with a relatively gripping section on re-binding, explores the children’s library (“books open magic doors for the young”) and drops into lunchtime “gramophone record recitals” where listeners sat in seance-like silence as classical LPs rotated with stately confidence in the future of HMV.

Oh what a wonder the Central Library was, with the librarians showing off an original letter written by Mary, Queen of Scots, leading story-telling sessions for schoolchildren and poring over books to answer postal queries (“Here’s a bit of a teaser from abroad: What’s the safe maximum rotating speed of cutlery glazing wheels? All in a day’s work for experts who have the right tools at hand!”).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd there are some lovingly lingering shots of assistants staffing desks at the civic information service, advising grateful ratepayers. The Service, library regulars will notice, used to occupy the room that now houses the computer and internet centre.

Mary Grover’s National Libraries Day talk is at Sheffield’s Central Library next Saturday, February 9, at 2pm. Places are free but must be booked on 0114 273 4727 (email: [email protected]). Potential contributors can contact her on 07966 501612 (email: [email protected]).