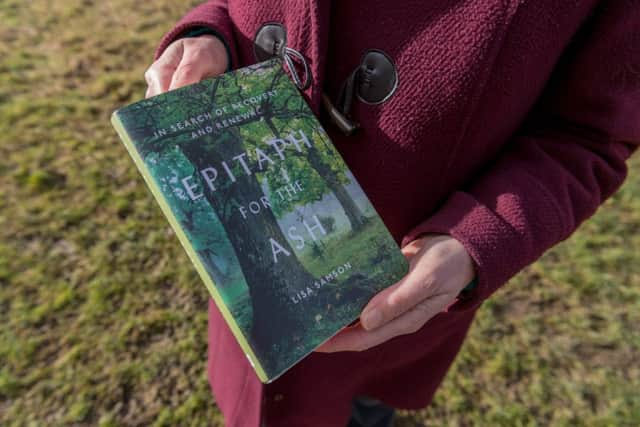

Lisa Samson on surviving a brain tumour while writing new book Epitaph for the Ash

Now Lisa Samson tells Sarah Freeman how her tribute to the ash tree also became a chronicle of her own battle with ill health.

Lisa Samson remembers well the spring day in 1978 when her mother came into the living room proudly holding a copy of the Sunday Times Magazine. Inside was an article on Lisa’s uncle, Gerald Wilkinson. Know to the family as the ‘eccentric tree expert’ his latest book, Epitaph for the Elm, a chronicle of the devastating progression of Dutch Elm Disease, was just out, and had begun attracting considerable Press interest.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I didn’t know him all that well, but every so often he would stop by his old Volkswagen camper van on his way to or from some woodland or other,” says Lisa, who lives in Harrogate. “I grew up in a town, but I always had a yearning for the countryside and his seemed the most romantic way to spend your life.”

When Gerald died in a car crash 10 years later, he became something of a mythic figure in the Samson house and, as Lisa’s own interest in nature deepened she often referred to his various books.

It was probably inevitable then that when Ash Dieback hit the headlines, Lisa began wondering whether it was time to write a sequel to her uncle’s earlier work. The idea was simple. With another death sentence hanging over another species of tree, she wanted to trace the cultural significance of the ash, explore the role it plays in folklore and mythology and examine its impact on British woodlands.

However, when she was diagnosed with a benign brain tumour the book turned into so much more. Epitaph for the Ash is all the things Lisa initially wanted it to be, but now it is also interwoven with her own journey of rehabilitation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“At first I thought I had progressive hearing loss,” she says. “But an MRI revealed a large growth on the right hand side of my brain. It was benign, but I needed surgery. The internet told me that only one person in a million is unfortunate enough to develop an acoustic neuroma, but when I began telling friends about it, a few knew of someone with the condition. The good news was all had survived.

“It reminded me of the reaction to Ash Dieback. Initially people were shocked and then it all made sense. Those in the know were not surprised. It was bound to reach Britain sooner or later and when I looked back I also saw symptoms which I had been ignoring.

“There was a lot of uncertainty, neither me or the ash really knew what was in store for us. We had to put trust in experts, me in the surgeons at Leeds General Infirmary, them in the research scientists.”

The ash occupies a peculiar place in British history. The Druids regarded it as sacred, it was the wood of choice for ancient weaponry and it has provided the root for countless place names. It was appropriate then that it was the village of Ashwellthorpe in Norfolk where in 2012 the Ash Dieback disease was first found in the wild.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It looks like the Enchanted Wood of Enid Blyton’s books and right there is one of the most photographed trees in Britain,” says Lisa. “It was Steve Collin, head forester of the Norfolk Wildlife Trust who first noticed the diamond -shaped lesion on the sapling’s thin trunk.

“They are now managing the decline, but when they have all gone, the ash in Ashwellthorpe will be nothing more than an historic reference. These trees have been part of the landscape for centuries, but, within a generation, great swathes of them could be no more.”

Lisa’s journey took her from Colt Park Wood in the Yorkshire Dales where the ash provide shelter for flora and fauna to Keswick in Cumbria and Branscombe in Devon and everywhere she collected stories about the ash, some uplifting, some poignant.

“One Devon farmer I met like most was a resilient sort. He didn’t know where the infected saplings he had planted some 20 years earlier had come from. Like most landowners at the time he had trusted his suppliers and had not thought to ask about the trees provenance.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“When he spotted the first signs of Ash Dieback he had to dig a pit 40ft long to burn the diseased trees. He told me at the shame he felt at having to hang the red warning signs at every entrance to his property, announcing the farm is a diseased zone.

“He said the community had been largely supportive, but one fellow farmer who he had known for years had accused him of bringing the disease to the south west. The truth is even large organisations didn’t chek the provenance of the trees they planted. The guilty ones are the importers who knew the disease was rife in the countries they were buying them from and the Government, who took no action until it was too late.”

For a moment, Lisa too thought she also might be staring at her own obituary. Two days after the initial operation to remove the tumour, doctors discovered bleeding in her brain. The only option was to take out a piece of her skull, but further surgery came with huge risks, including the chance that Lisa could be left with locked-in-syndrome.

“I didn’t know what the world would look like when I woke up again or even if I would wake up again, but I had no choice.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLisa, who as a result of the surgery, feels uncomfortable being photographed, did wake up and, like the ash, she too proved her inner strength. “I spent a year learning to walk and talk again,” she says. “The right side of my face was frozen and initially I could only speak with the left side of my mouth and was fed intravenously for nearly a month.

“For a while I thought that was it for the book, but it was my editor who suggested I should go back to it. Having not been able to walk in the countryside for so long, my first time in woodland was really special and I felt even more of an affinity with the ash than I had before. Some were sick, but others were growing leaves showing they intended to live on, at least for now.”

In old Norse mythology the ash is known as the Tree of Life and, according to the legends when it dies the world as we know it will fall. Ash Dieback may have done its best to finish off the species, but with research scientists there may yet be another chapter for the tree – and for Lisa.

“Yorkshire would seem barren without the ancient ashes protruding from limestone scars and chalky cliff faces. I hope we don’t see the day when the only way our grandchildren can glimpse an ash is in special nature reserves and behind the scenes a small army of people are doing all they can to prevent that from happening.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The important thing though is that we learn lessons for the future so that we do all we can to prevent the spread of similar diseases.

“As for me, well, things are not as I would like them to be, but they are as they are. I don’t think I can ever return to how I was before because so much has changed. I still have to have scans every six months and I don’t think the psychological scars will ever be erased, but, a bit like the ash, I am still holding on.”

■ Epitaph for the Ash is published by Fourth Estate, priced £12.99. Lisa will be signing copies of her book at the Imagined Things bookshop in Parliament St, Harrogate, on April 7, from 11am to 2pm.