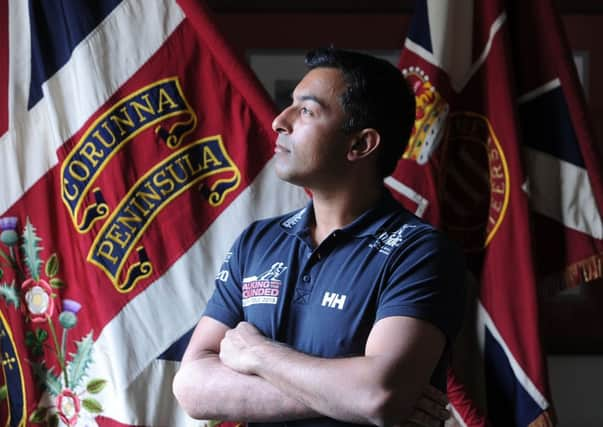

Middle East furnace to life in freezer for wounded soldier

THE last time I spoke to Ibrar Ali it had just been announced that he was part of a team of wounded British servicemen and women taking part in a race to the South Pole.

Since then the 35-year-old from York has been training in Iceland, climbed Kilimanjaro and run the Yorkshire Marathon, in preparation for the 208-mile (335km) Walking With The Wounded South Pole Allied Challenge, which begins next month.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAli, or “Ibi” as he prefers to be called, is a former British Army captain and part of Team Glenfiddich UK involved in a race against teams from the United States and the Commonwealth. It’s the third expedition the Walking With The Wounded charity has organised and sees Prince Harry joining Ibi and three other injured service personnel in the British team, with the aim of raising money for the organisation which supports injured servicemen.

Ibi himself was badly wounded while serving in the Yorkshire Regiment in 2007 when his patrol was hit by a roadside bomb. One of his colleagues was killed in the attack in which he lost his right arm.

Just 18 months later he was back on tour with the army in Iraq. But now he’s taking on a new challenge, swapping the heat of the Middle East for the freezing temperatures of Antarctica.

“We had a trip out to Iceland in July where we did some team training and Prince Harry joined us and then in September we did some further training in the cold chamber,” he says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe cold chamber, normally used for testing vehicles in extreme temperatures, gave them a taste of what they might encounter with temperatures dropping as low as minus 50 degrees. “It was eye watering, to the extent that the minute you walked into the chamber your eyebrows froze.”

It was a crucial test for the soldiers and veterans. “It was important to see how our stumps would be in terms of reacting to the cold and we worked out that they do get very cold, so it’s something we know to be careful of.”

Ibi, who left the Army in August, says he’ll be doing a minimum of four hours a day over the next month in order to build up his strength and stamina as each of them will lose around a stone in weight during the expedition.

“This is my second gym session today and I’ll spend two hours on the cross-trainer before bed and then it’s back here for 7am tomorrow.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was part of a team that trekked up Kilimanjaro which he says was a valuable experience. “It was tough and one of the days we walked 12 or 13 hours, but it was a fantastic experience and great preparation especially the altitude.”

Ibi believes that his injury has made him mentally tougher. “When you go through something like that it does make you stronger. I’d not done a marathon prior to the injury and that helps strengthen the mind, because the body will go where the mind puts it.”

Even so, he’s aware of the size of the task ahead.

“There’s a huge amount of apprehension and it’s a bit like prior to my first operational tour.

“You’ve trained as much as possible, all the kit is packed and you know when you’re going.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“But it’s such an unknown environment, 20 hours in the cold chamber isn’t the same as three weeks in the South Pole.

“You can prepare for the sights, sounds and smells but it’s not until you hit the ground, like in Basra or Camp Bastion, that you know what it’s like.

“But we’re as prepared as we can be.”

Although he’s now left the Army and is planning to go to university next year, he wants to help the charity.

“We’ve had the chance to meet some of the guys who have benefited from their work. Some of them were in a dark place, and some of them may still be in a dark place, but they can see the light and the retraining of these guys perhaps feels more important than it did six months ago.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I find it quite daunting and without wishing to sound arrogant if someone like me who became a young officer and who went to university is finding it daunting to go back into education, then how’s that 18- or 19-year-old soldier who’s missing a leg or dealing with mental illness going to find it?

“It will be on the long, lonely days on skis with a set of goggles and face mask on, that’s when we’ll really think about why we’re doing it and we’ll realise it’s for the greater good.”

To find out more visit www.walkingwiththewounded.org.uk