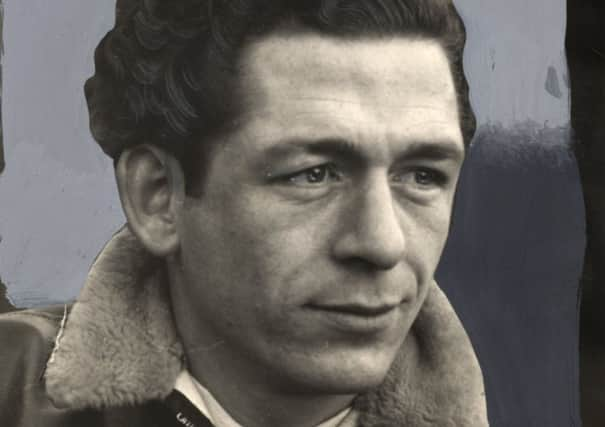

Derek Kinne, Korean War hero

He spent 28 months in captivity, having been taken prisoner in 1951, on the final day of the Battle of Imjin River.

The defiance he showed his captors saw him placed in solitary confinement, in the most brutal conditions. He escaped twice, the first time within a day of his capture, but even under duress managed to cock a snook at the Chinese by putting on a rosette to celebrate the Queen’s coronation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe had gone to Korea with the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers because he had made a pact with his brothers, Raymond and Valentine. In 1947, they were said to have bought three rings at a jeweller’s shop in Leeds, which they had inscribed Kinne I, II and III. They made a solemn pact that if one of them was killed in action, another brother would take his place.

Raymond’s death came in Korea, in October 1950 and as soon as the news came through, Derek presented himself as a volunteer at Leeds Recruitment Office.

The following February, he sailed for Korea with Raymond’s regiment, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, and set off to find his brother’s grave.

The Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, wrote to their widowed mother, Vera, to say: “You must be proud of your boys. May I express my most sincere sympathy with you.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThree months later, Derek was reported missing. Valentine asked his depot at Pontefract Barracks for compassionate leave but back home in Beckett Street, Burmantofts, Vera placed a moratorium on him going to Korea as well.

In captivity, Derek resolved first to escape and then to try to raise the morale of his fellow prisoners.

Having been retaken a few days after his first attempt, while he attempted to return to his own lines, he joined a large group of inmates being marched north to prison camps. By now well known to his captors, he was accused of noncooperation and was brutally interrogated about other prisoners.

As a result of his refusal to inform on his comrades, and for striking a Chinese officer who assaulted him, he was severely beaten, and tied up for 12 and 24 hours at a time. They made him stand on tiptoe with a noose around his neck which would throttle him if he attempted to relax.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe escaped again in July 1952 but was recaptured two days later and put in handcuffs that were tightened so as to restrict his circulation. He remained shackled for 81 days – after which he was made to stand to attention for seven hours and beaten by the Chinese guard commander with the butt of his submachine gun.

The gun went off and killed the guard, and by way of punishment, Derek was beaten senseless with belts and bayonets, stripped of his clothes and thrown into a dark hole, infested with rats, and left there until September 19.

A few weeks after that, he was tried for escape and for being a reactionary, “insincere” to the Chinese. They sentenced him to 12 months in solitary confinement, and when he complained about the denial of medical attention, they added another six months.

Later he was transferred to a penal company, but when he wore his Coronation rosette he was placed back in solitary.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was eventually released in a prisoner exchange in August 1953.

He was awarded the George Cross the following April. The citation ended: “Every possible method both physical and mental was employed by his captors to break his spirit, a task which proved utterly beyond their powers.”

He was presented with the medal at Buckingham Palace by the new Queen whose rosette he had worn.

By that time, his defiance was legendary and he was known as “the man North Korea could not break”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe wrote an autobiography, The Wooden Boxes, in which he described the guard’s accidental shooting. “I was beaten until I longed for death,” he wrote.

Fusilier Derek Godfrey Kinne was born in Nottingham and had been working at a hotel and running a small washing machine business in Leeds, renting out by the hour Hoover single-tubs with wringers attached, when he put his name forward for the Korean Volunteers Scheme.

He did not remain long in Britain after the war. In 1957, he moved to North America and married Anne, also British, in Ottawa. Two years later, the two of them arrived in Arizona, bought a house and set up a framing and laminating business in Tucson. He retired in 2005, at 74. In the spring of 2010 he returned to Korea, with some of his family, to mark the 60th anniversary of the war.

He is survived by Anne, son Raymond, daughter Deborah and four grandchildren.