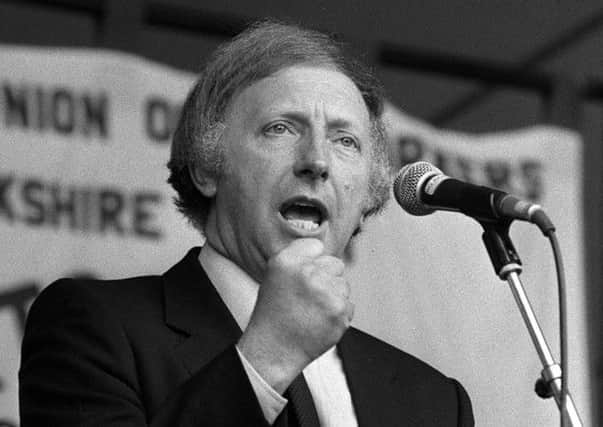

Bernard Ingham: Why Scargill’s downfall was the salvation of democracy

It is not how 1984 will be seen across swathes of the country, notably South and West Yorkshire.

My assertion will be mocked wherever two or three Lefties are gathered together to analyse the 1984-85 miners’ strike.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe BBC, as is its wont, has already tried to justify Arthur Scargill because secret papers just released show that Sir Ian MacGregor, the politically vacant and hapless chairman of the National Coal Board, had, in fact, plans to close around 70 pits.

It conveniently failed to note that, whatever ideas MacGregor might have had, he did not make government policy.

No government – no, not even Margaret Thatcher’s – would have contemplated closing 70 pits just like that, even though it was pouring escalating subsidies into them – a total of £2,256bn between 1974 and 1984. It was Scargill’s utter arrogance, born of a fundamental stupidity, that substantially did for deep coal mining in Britain.

It was perhaps the inevitable consequence of the unions’ abuse of power that its Brigade of Guards, as the NUM was sometimes described, should be slaughtered in Scargill’s last stand.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI take no pleasure in that massacre. Don’t forget, I was brought up in a Labour and trade union home. My father was a Labour councillor and minor weavers’ union official in Hebden Bridge. He used to take me to hand over subs to Lewis Wright, later a member of the TUC’s general council, at his Todmorden office.

I held NUJ office in Halifax, Leeds and London, wrote weekly for Labour’s Leeds Weekly Citizen and was heavily defeated when I stood for Labour in Leeds City’s unwinnable Moortown.

Half a dozen constituencies in Yorkshire offered me the chance of selection as a Parliamentary candidate, but I jibbed at the idea of seeking union sponsorship. I was already having doubts about union power.

My experience as a labour correspondent for the Guardian and then as press secretary in the Department of Employment intensified those worries. Barbara Castle, no less, sought through her misnomered White Paper “In Place of Strife” to complement union power with responsibilities. A union-dominated Cabinet threw it out.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI spent much of my time in the Employment Department choreographing conciliation of strikes at 8 St James’s Square into the early hours.

German journalists regularly ribbed me about “the sick man of Europe”. Official figures show that 128m days were lost through 25,924 strikes during the 1970s.

When I went to the Department of Energy exactly 40 years ago, Ted Heath’s government soon went down to defeat at the hands of the miners.

A Labour government then had the mortification of presiding over the strike-filled “winter of discontent” in 1978-79 that led to Thatcher’s eventually purgative arrival in No 10.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy then the nation was so demoralised that it doubted whether it was governable any more. Few believed she would make much difference or last all that long.

Which brings me back to that historic year: 1984. Thatcher had no appetite for union confrontation. She, the economy and the nation needed it like a hole in the head.

But she knew – as did any discerning person – that Scargill’s appetite was now for humiliating governments, not just the NCB.

The miners, drummed into line as necessary without a proper ballot by flying pickets and just plain thuggery, were mere pawns in Scargill’s political game.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIf the nation – indeed, its Parliamentary democracy – was to have a future, he had to be defeated. It was as simple as that. He was, but it was a close-run thing. Fortunately, other unions were more restrained than revolutionary.

The result was that mining communities were sacrificed on Scargill’s militant altar. A burden was lifted from the economy. Union power was discredited. The movement lost half its membership.

Thirty years on it shows little sign of recovering, though Len McCluskey, of Unite, is again trying to pull Labour’s strings.

He needs watching, not least by the trade union movement itself.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIf Thatcher had achieved nothing else, she would still have astounded the country by bringing the unions within a framework of law.

In doing so, she rescued a Parliamentary democracy that would have had nowhere to go if Scargill had triumphed.

She did not, however, complete the job. Westminster is still subservient to Brussels.

But 1984, when the domestic battle was effectively won, is still a landmark in our history. I think George Orwell, scourge of tyranny, would be pleased at the outcome.