Grant Woodward: The Human Rights Act is not perfect, but remember that it protects us all

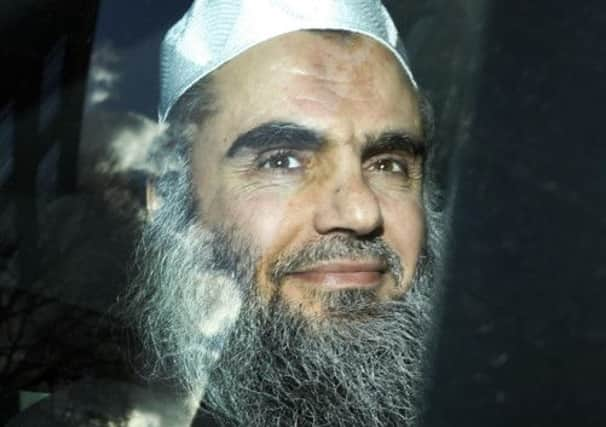

She has intensified her attack on European judges for blocking Abu Qatada’s deportation and recently told a Conservative get together that the party would leave the European Convention on Human Rights if it won the 2015 election, because it restricted the UK’s ability “to act in the national interest”.

The Home Secretary’s low opinion of the legislation, first enshrined in UK law 15 years ago, is undoubtedly coloured by her inability to secure the extradition of the man once dubbed Osama bin Laden’s right-hand man in Europe and who currently languishes in the high-security Belmarsh Prison in London after breaching his bail conditions.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYet, while the radical preacher’s continued presence in this country might give Mrs May an ace card to attack human rights legislation, she threatens to attack the rights of every law-abiding individual.

Don’t get me wrong – the Human Rights Act is far from perfect, but that doesn’t mean it should be written off completely.

It is worth remembering that while this country’s long and proud history of recognising individual freedoms dates back to the Magna Carta in 1215, the document says nothing about the right to be free from undue state interference in our private lives. Nor does the Bill of Rights, which in 1689 reasserted many civil liberties, mention the right to free expression and freedom from discrimination.

The horrors of the Second World War, which saw millions persecuted on the grounds of their race and religion, demanded that such rights were formally recognised in international law. This led to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, followed by the European Convention on Human Rights, which sought to enforce the safeguards it mapped out. The UK became the first state to ratify the convention in March 1951.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, until the Human Rights Act received Royal Assent in November 1998, British judges and public authorities were not bound to observe it as a matter of UK law. Anyone claiming that the Government, police or any public body, had breached their fundamental rights had to make a claim before the Strasbourg court.

Since then, the Act has been responsible for averting an untold number of miscarriages of justice. They include the instance of the young man whose ear was bitten off during an altercation in a London café, only for the case against his alleged attacker to be dropped on the basis that the victim’s mental health condition meant he could not be put before the jury as a reliable witness.

The High Court held that the decision to terminate the prosecution on such grounds breached Article 3 of the Human Rights Act, which prohibits inhuman and degrading treatment. Such a decision not only humiliated the victim and discriminated against him, but by dropping the case the state had failed to provide proper protection against serious assaults through the criminal justice system.

Then there was the case of Naomi Bryant, who was murdered by convicted sex offender Anthony Rice in 2003 after a catalogue of mistakes had resulted in his early release on licence.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFollowing Rice’s admission of guilt, the coroner took the decision not to hold an inquest into Miss Bryant’s death. The civil rights group Liberty, acting on behalf of her mother, used Article 2 of the Human Rights Act to obtain an inquest into mistakes that led to Rice’s release. Its lawyers argued that government bodies did not adequately consider the safety of the public, particularly women, when they released him. The inquest finally took place in 2011, when a jury concluded that failings by the probation and prison service, police and others contributed to the tragedy.

Without the Human Rights Act, these – and countless other – gross miscarriages of justice would have gone unchallenged.

When it comes to Abu Qatada, the act is similarly unequivocal. While it states that there can be a limitation on someone’s rights if it is in the interests of national security, Article 3’s insistence that an individual’s protection from the threat of torture is non-negotiable means the judges in the Qatada case had no option but to block his extradition to Jordan, a country where the use of torture is widespread. Some will say that in the case of Qatada, a man whose hate-filled sermons gave “spiritual guidance” to the 9/11 bombers, we should be happy to make an exception. Torture, they will tell you, is too good for him. But once you start making exceptions, where do you stop?

Frustrated by the lack of willing shown by their Liberal Democrat coalition partners – and no doubt chivvied along by Theresa May – Chris Grayling, the Justice Secretary, is now urging Ed Miliband to support the Conservative push for “radical reform of our human rights laws”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is a call the Leader of the Opposition must resist. Instead he should listen to Labour grandees such as ex-Home Secretary John Reid, who have expressed concern that the Qatada debacle should not be allowed to undermine faith in the entire human rights regime.

“The danger in the long run is that if people believe the law as it stands... is open to misuse, then the demand grows to throw out the whole thing,” said Lord Reid.

It is certainly unfortunate that such a high-profile case has skewed our perception of the Human Rights Act. But for all the frustration caused by Abu Qatada’s lingering presence, we should remember that it is a piece of legislation which affords every one of us protection from any attempt by the state to curb those rights and freedoms that we hold dear and presently take for granted.

If that means Britain has to continue to pick up the bill for keeping the likes of Abu Qatada on a tight leash then, as galling as that may be, it is still a price worth paying.