Malcolm Barker: Remembrance that could provide a useful template

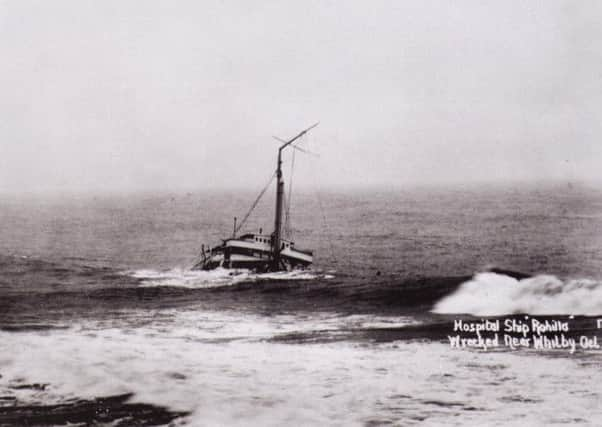

Most will call for a delicate balance between recalling those who died and celebrating acts of courage and self-sacrifice. These often occurred in the midst of the most dreadful events, and an early example is the loss of His Majesty’s Hospital Ship Rohilla on October 30, 1914.

She was in the news again last Saturday in a fascinating Yorkshire Post report of the acquisition of a trunk belonging to a nurse called Mary Roberts, who had already survived the Titanic sinking, and who was plucked from the wrecked hospital ship by the Whitby lifeboat John Fielden. The trunk which she had taken aboard Rohilla turned up at a house clearance in York, and was bought for Whitby Lifeboat Museum by Peter Thompson, its honorary curator, when offered for sale on eBay.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRohilla went ashore on the Scaur, a shallow rocky reef between the East Pier at Whitby and Saltwick Nab, at around four o’clock in the morning, amid a furious gale that thwarted the most gallant efforts of lifeboatmen, who struggled for 52 hours to bring off survivors. Whitby knew the pain of failure, for the silent crowds gathered on the cliff near the Abbey ruins could only watch as men were swept to their deaths. No rocket line could be attached to the wreck, and no boat could be laid alongside to bring them ashore.

There was grievous loss of life, 92 in all, and, at the opposite end of Yorkshire another town about the same size as Whitby, Barnoldswick, was cast into mourning. Twelve of the 15 members of its St John Ambulance Brigade were lost. They had all volunteered to serve as Royal Naval reservists, and had been called up on the outbreak of the Great War, joining Rohilla as sick-berth attendants.

Like the others who perished, they were as much the casualties of war as those killed on the battlefields. Rohilla had sailed from Leith in Scotland on Thursday, October 29, bound for Dunkirk to take on board casualties from the first Battle of Ypres, which had begun 10 days previously.

She was needed urgently, and there was no time to wait for the weather to ease. War-time restrictions meant that shore lights providing navigational aids were extinguished, and as a great storm gathered force Rohilla headed towards the English Channel by dead reckoning. She strayed off course eastwards by as much as seven miles, and when she was sighted by a Whitby coastguard, Albert Jefferies, in the small hours of Friday morning she was heading at speed directly towards the Scaur. Mr Jeffries must have been startled to see a ghostly white steamer in such dangerous waters, but he kept his wits about him, signalled a warning with a Morse lamp and set the foghorn bellowing.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn board Rohilla the officer on watch saw the light, but was mystified because he could not imagine who might be signalling to them seven miles out at sea. The bell-buoy that might have warned him of the miscalculation had been silenced, and its light dowsed. Rohilla struck the undersea hazard known as Whitby Rock and moments later drove hard ashore and split her hull apart on the Scaur. Her master, Capt David Landles Neilsen, who had been with Rohilla since her launch in 1906, ordered all hands to boat stations. Many who had been asleep below probably died quickly, for the ship came apart and water flooded in.

On the 50th anniversary of the disaster, in 1964, I had the privilege of talking to two of the three Barnoldswick survivors, Fred Reddiough and Anthony Waterworth. Both were anxious to pay tribute to one of the early heroes of the Great War. He was a man of 48, bespectacled, balding, a Roman Catholic priest from Swansea who volunteered to serve as a Royal Navy chaplain at the outbreak of war.

I printed his name as Canon Gwydr half a century ago, and in doing so committed a cardinal sin of newspapermen, getting someone’s name wrong. I have also seen it on memorials as Gwyder, but now, thanks to the appearance on the internet of an archive of the Roman Catholic periodical Tablet, I can give a very gallant gentleman his full name: The Very Rev Robert Basil, Canon Gwydir.

He was on the deck of Rohilla when he encountered the two Barnoldswick men, but heading down below where waves were already flooding the companionways and lower decks, intent on keeping a patient called Nicholson company. This man, a Royal Marine, had been severely injured in a coaling accident in the Firth of Forth, and doctors had decided his best hope of recovery was to remain immobile on the ship while she sailed to Dunkirk and back.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCanon Gwydir was not seen alive again, but his body was soon washed up, and his funeral took place the following Tuesday, November 4. The man to whom he had gone to give succour also perished.

There were other heroes in plenty. Thomas Smith Langlands, the coxswain of the Whitby lifeboat John Fielden, realised that the fury of the sea rendered the harbour bar impassable. He decided on a launch from the Scaur, and at dawn that wild morning the John Fielden was manhandled on to the rock platform. She was launched from nearly opposite the wreck and Tommy Langlands shouted encouragement to his crew as they bent to their oars: “Come on, my bonny lads!”

Twice they laid alongside Rohilla, bringing off 35 people, including all her womenfolk. But soon the tide was flowing across the Scaur, and the lifeboat was herself a wreck. Further attempts at rescue by other rowing lifeboats were unavailing, and it was not until the Sunday morning that a motor lifeboat, the Henry Vernon from Tynemouth, brought off the last survivors.

Capt Nielsen was the last man to leave his ship, carrying Rohilla’s cat.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis extraordinary epic is being commemorated in a number of ways. In Whitby, the Civic Society and members of the lifeboat crew are arranging a series of events, including the unveiling of a plaque on the West Pier, the laying of a wreath at sea, and a service at St Mary’s Parish Church, whose bells rang out in 1914 to welcome Henry Vernon and the last survivors. In Barnoldswick a plaque referring to the town’s loss of life was added to the War Memorial last July. The Royal National Lifeboat Institution is arranging for the wreck to be featured in a touring exhibition marking the centenary of the Great War.

Thus the balance is being struck between grief for those who died and admiration for dauntless gallantry. The remembrance of Rohilla may be a useful template for the centenaries that will be reached during the succeeding months and years.

• Malcolm Barker is a former editor of the Yorkshire Evening Post.