Marine bird deaths highlight frightening impact of climate change: Tim Birkhead

Puffins, guillemots, penguins and albatrosses are all in decline. How do we know this? There are three main ways of checking on numbers. First and best are long-term population studies: counts of individuals or pairs at their breeding colonies made in a systematic, rigorous way each year at established “study plots”.

Occasionally, numbers spike in what in seabird parlance is known as a “wreck”, as occurred in 2014 when more than 50,000 seabirds, mainly guillemots and puffins, were washed up on the west coast of Britain and France. Seabird wrecks have been known about for a long time, but they are becoming more common.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWrecked seabirds are usually emaciated, having usually starved to death, indicating a catastrophic failure in their food supply. This is exactly what happened in late 2016 on the remote island of St Paul, in the Bering Sea between Alaska and Russia. According to a new study published in the journal PLOS ONE, around 285 tufted puffins were found dead over a three-month period – many times more than the usual background level of death. Note, the tufted puffin is a bigger, chunkier, darker bird than its relative the Atlantic puffin that breeds around Britain’s shores.

A total of 285 doesn’t sound dramatic, but it is well known that only a fraction of the birds that die get washed up and found. The authors of this report use a variety of sophisticated methods to calculate the true mortality and come up with an estimate of between 2,740 and 7,600 – and this from an estimated tufted puffin population on St Paul of 7,000 individuals.

This was far from being a trivial event. Indeed, it seems to be part of massive shift in the marine environment, a “Pacific marine heat wave”. This is global warming writ large upon the seas, causing changes in the abundance and distribution of plankton, with knock-on effects on the fish and invertebrate species that tufted puffins and other marine birds need to feed on.

Seabird wrecks are often associated with stormy sea conditions (as in the UK in 2014), which themselves are a symptom of climate change. Yes, we’ve always had storms, but storms are occurring more frequently and are more intense than previously. High winds and rough seas are thought to disperse fish shoals and make it hard for seabirds to find enough food.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut the puffin wreck in the Bering Sea was not linked to stormy conditions. Instead, the scientists involved think that warming of the seas by just a couple of degrees was enough to reduce the availability of food. Add to this the fact that puffins were moulting – replacing their feathers – at this time of year, placing extra energetic demands on them, and probably limiting their ability to search for food over a wide area. The result: starvation.

The events around St Paul Island are part of a much bigger picture of ongoing decline that is almost certainly caused by ongoing climate change. We cannot afford to ignore the signs that climate change is not just continuing, but accelerating, and as that happens populations of seabirds (and many other forms of wildlife) will continue to decline.

We need to ensure we have robust monitoring systems in place to document these depressing changes in bird numbers, and we need to do everything we can to reduce the root cause: climate change.

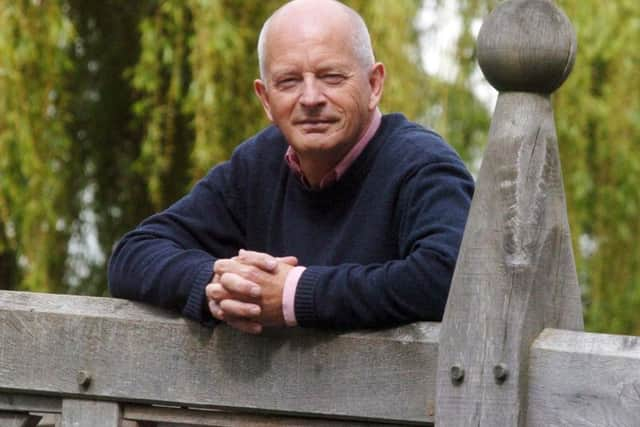

This article originally appeared on www.theconversation.comTim Birkhead is Emeritus Professor of Zoology at the University of Sheffield.