The original war air aces who risked their lives

These terrifyingly flimsy contraptions may have seemed like they were held together by string and sealing wax but they were in fact the Royal Flying Corps heading off to the front.

The popular image of the First World War in the air tends to be of fighter aces locked in gladiatorial combat. But to begin with the Royal Flying Corps, which had only been created two years earlier, were the eyes of the Army.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAircraft were used for reconnaissance in August 1914 when they played an important role in locating German troop movements which aided the British retreat from Mons. In these early days there was a pilot and an observer and whereas later in the war fighter pilots were feted as heroes, initially they were seen as little more than chauffeurs with the observers doing the important work of spotting enemy guns.

Among those who took part in these initial reconnaissance flights was Harold Jameson, from Whitby. He joined the Royal Flying Corps as a mechanic when he was just 17 years old and quickly volunteered to be an observer. He was involved in the retreat from Belgium and quickly made his mark after he was awarded the Medaille Militaire by the French president Raymond Poincare for “conspicuous bravery” during operations between August 21 and 30.

On one occasion he was flying over German lines when his pilot injured his hand. Despite the fact his plane was attacked by anti-aircraft guns and one of the engine valves had been shot away, he continued to send important wireless messages back to HQ and they finally made it back to safety.

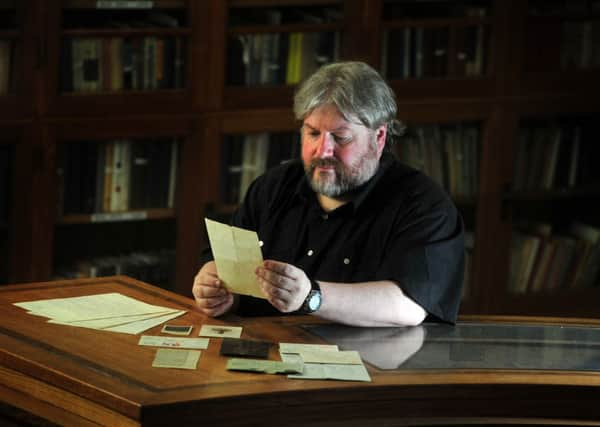

A number of his wartime belongings, including several photographs, as well as letters and postcards sent to his mother in Yorkshire, were bequeathed to the Liddle Collection at the University of Leeds, by his late sister, the novelist Storm Jameson.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey chart his impressive rise through the ranks. By 1916 he was a second lieutenant and had been awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal and in November that year he won the Military Cross for attacking a German kite balloon while under heavy fire.

By now he had become a pilot which he mentions in a letter home to his mother. “Just a few lines to let you know I have left the front for a time. I am down in a seaside place called Le Crotoy on the Somme.

“I am down here on a course of flying training to be a pilot. Today I had my second lesson and for about 10 minutes I had full control of the machine – just think of it, sailing along at 65 miles an hour a thousand feet in mid air and having the power to make the machine go up or down, right or left, it is a glorious feeling.”

Whether his mother shared his excitement is debatable given the fact that many pilots were killed in training accidents before they even had the chance to face the enemy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe romantic image, fuelled by Hollywood, still persists of air aces whooping it up in ramshackle French farmhouses, or requisitioned chateaux, but the reality for most airmen was far more prosaic. Their quarters were more likely to be a tent in a field, as Jameson describes in a letter home in August 1915. “The floor is the good old earth kept dry by a small trench dug right round it,” he writes. “The table is a sheet of ebonite I have borrowed from the stove. One thing about active service you find out very soon that there is nothing you cannot do without.”

The green envelope which contained the letter looks as though it was torn open, probably by his mother who was no doubt eager to hear from her son but at the same time full of dread about what might have happened to him.

Like so many letters home, though, he spares her any of the harrowing details he no doubt witnessed and instead tries to soothe her fears. He finishes by saying: “I think when the war is over I will put all my worldly goods in a pack and go and bury myself in Brazil. Well I will have to finish now as the time is going just about as quick as my candle is. From your loving son, Harold.”

Sadly, Jameson didn’t live to see the end of the war. On January 5, 1917, he was killed in action along with an observer after being shot down over No Man’s Land having just attacked a German artillery site.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNews of his death was carried in the local Press in Whitby, where Jameson had clearly left his mark during his short life.

One newspaper report said his “brilliant exploits” had reflected great honour on the town, adding: “As a boy, he was of a fearless disposition and generally led the way among his chums with daring tricks, one of them being to be lowered over the cliffs with a rope.”

Several letters were sent to his grieving family praising his “gallantry and courage”, including a moving tribute from a “Captain Murray” who wrote: “The deepest sympathy may appear futile in such sorrow but it may comfort you to know that ‘Jamie’ was regarded as our stoutest and best hearted pilot. In fact there was more of the spirit of affection in the attitude of his brother officers towards him than in any other case I have yet encountered in the Army. I could say much more but, after all, what better could be said than the above, we are all losers.”

It was said of pilots in the First World War that they were mostly “a little over 20, former public schoolboys and soon dead”. For Harold Jameson this proved tragically accurate.