Out of the blue... Yorkshire researchers unearth proof that women were behind the great works of the Middle Ages

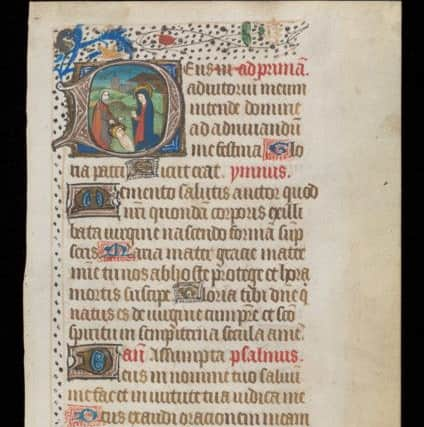

Remarkable research, published last night by a Yorkshire academic, suggests that contrary to what was written at the time, the artists behind some of Europe’s most richly illustrated books may have been nuns and not monks – their roles subverted by the lack of esteem in which they were held.

The clue to a discovery that may change the way history views the scribes of the Middle Ages, was contained in fragments of ultramarine pigment made from the precious stone lapis lazuli, which was mined in Afghanistan during the medieval period and prized for its intense colour.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was used in paintings and to decorate books of the highest quality, with which only the most skilled scribes and painters would have been trusted.

Yet it has now emerged that traces of the pigment were trapped within the teeth of a female skeleton in the grounds of a monastery that was once home to a community of nuns, and now stands in ruins at Dalheim in the German Rhineland.

“There were very many specks, and they were scattered across the carcass, suggesting that they had entered the mouth as air particles in the form of dust,” Dr Anita Radini, from the department of archaeology at the University of York, told The Yorkshire Post.

Her research suggests that the pigments may have got into the woman’s mouth as she used her tongue to hone her brush into a fine point in order to paint intricate detail on manuscripts – a technique referred to in contemporary texts.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe discovery came, literally, out of the blue, Dr Radini said.

“In nature, there are a variety of pigments of red and yellow, but blue pigments are very rare. In the Middle Ages and earlier, the most important resource for the colour was lapis lazuli.

“I was surprised. It was the first time I had seen such strong evidence. It tells us that this woman was very likely involved in the activity of making pigments and painting.”

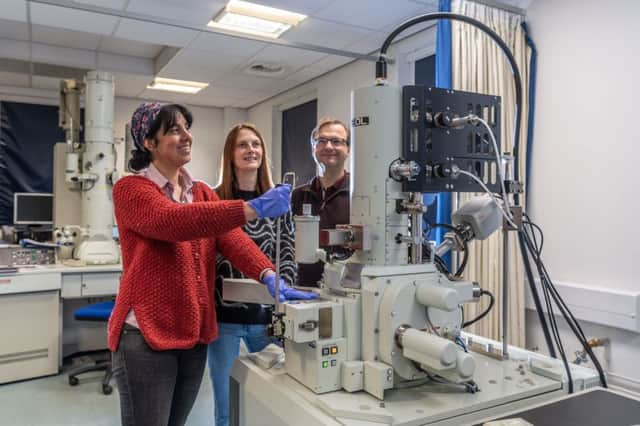

Dr Radini, whose research is published in the journal Science Advances, said the discovery – verified in York by examination of the dust using light and electron microscopy techniques – added to a growing body of evidence of the importance of nuns in medieval Europe.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“In Germany, women’s monastic communities were made up of noble or aristocratic women, many of whom were highly educated,” she said.

“These women would have lived lives free from hard labour and our skeleton fits this profile – it belonged to a middle-aged woman and showed no sign of occupational stress.”

She added: “Women were involved in more activities than we have seen so far. But they were less esteemed in society than men for many crafts.

“We believe they were neglected. Now, archeology can help to track what they did.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHer colleague Dr Christina Warinner, of the German Max Planck Institute, added: “Here we have direct evidence of a woman, not just painting, but painting with a very rare and expensive pigment, and at a very out-of-the way place.

“It makes me wonder how many other artists we might find in medieval cemeteries, if we only look.”

Dr Roland Kröger, a physicist at the University of York, said: “The distance over which the pigment travelled to be found in this skeleton in Germany shows the scale and global nature of the medieval trade in colours.”

The discovery may be the key to learning more about life in the Middle Ages, he added.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe traces were revealed by raman spectroscopy – a high-precision technique for identifying molecules.

“Using this method offers an unprecedented level of insight into the lifestyles and working conditions of our ancestors, and has prevented this woman’s involvement in the creation of manuscripts from being erased from history,” Dr Kröger said.

“It offers great promise for illuminating the lives of countless other women who quietly and anonymously produced many of the books of medieval Europe.”