How Albie Sachs survived car bomb to help Nelson Mandela build post-apartheid South Africa

“I just knew something terrible had happened,” says Albie Sachs, describing the moment his life as an anti-apartheid lawyer and activist was almost cut short in 1988 when a bomb planted by South African security agents detonated as he unlocked his parked car.

“There was suddenly total darkness. I heard a voice saying ‘You’re in hospital, your arm is in lamentable condition, you have to face the future with courage’. I said into the darkness ‘What happened?’ and a woman’s voice said ‘It was a car bomb’. I fainted, but into joy. I knew I was safe. I had that feeling they would come for me, and you’re waiting for it all the time.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSachs went on to become the chief architect of South Africa’s post-apartheid order, appointed by President Nelson Mandela as a constitutional court judge in his home city of Johannesburg, but at the time of the blast he was living in Mozambique. He had gone into exile in 1966, having been held in solitary confinement without trial and effectively tortured for his part in the resistance movement that sought to end racial segregation.

The blast in Maputo – which killed a passer-by – caused him to lose his right arm and the sight in his left eye, but Sachs drew strength and inspiration from the incident. “In a strange way the bomb blew away the unhappiness – that residue that been there since the solitary confinement. Surviving that gave me an enormous energy and optimism. They’d come to kill me, they’d tried and failed. If I could get better my country could get better.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

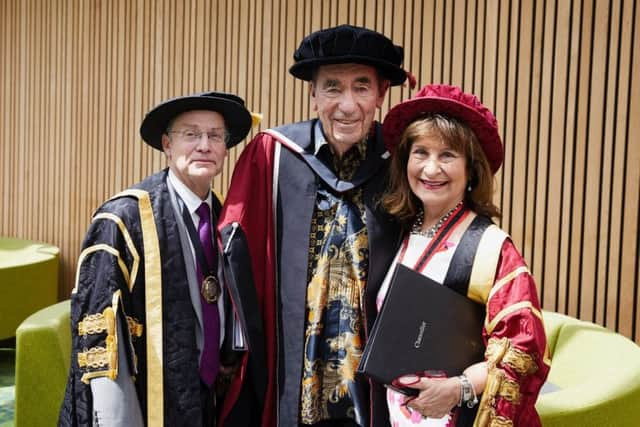

Hide AdSachs, now 84, stepped down as a judge a decade ago – “I don’t use the ‘retirement’ word, I’m in denial,” he says wryly – and he’s dressed in a suitably relaxed fashion when we meet in Sheffield, where he was awarded an honorary doctorate in law from Hallam University earlier this month. He’s settled in the lobby of his hotel wearing a Panama hat and a colourful, traditional African shirt –the same outfit, presumably, he wears at home in beachside Cape Town. Dignified and genial, he speaks thoughtfully and poetically about his life’s philosophy, an approach he calls ‘soft vengeance’.

“After the bomb I got a letter saying ‘Don’t worry, comrade Albie, we will avenge you’. I thought, avenge? What are they going to do, cut off their arm and blind them in one eye? If we get freedom, democracy and justice, that will be my soft vengeance. Roses and lilies will grow out of my arm. It’s more powerful. Hard vengeance is that relentless fight, just over who’s in command. Soft vengeance is the triumph of your ideas and goals.”

Activism was a fixture of Sachs’ childhood. His father, Solly, was a trade unionist and his mother Ray worked for Moses Kotane, leader of the Communist Party of South Africa; the couple were both immigrants from Lithuania who fled Jewish oppression in the Russian Empire.

After his parents separated, Sachs was brought up by Ray, whose job gave him a crucial insight. “A white woman working for a black man... For me, that was absolutely natural, and the world outside in South Africa was unnatural.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis father kept in touch, however – on his sixth birthday, with the Second World War at its height, Solly sent his son a postcard saying ‘May you grow up to be a soldier in the fight for liberation’.

“Which I think is pretty heavy, for a six-year-old,” says Sachs, chuckling. “I have three sons – none of them got letters like that from me.”

Oliver, his youngest child with his second wife, architect Vanessa September, is 12. Is he showing any familiar Sachs traits?

“He’s got certain qualities that would probably get him into trouble,” Sachs says. “He uses some of that against his parents in very clever ways that I admire... even when it hurts. I’d be happy if he chooses a profession he finds meaningful, engaging, challenging, testing and law can be that. It has been for me.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSachs had what may have been Cape Town’s busiest legal practice; half of his cases involved defending people being prosecuted under racist statutes. Judges, he says, were ‘all white, all men’. “Some of them had heart and compassion, and others went with the intention of parliament, which was to make the white superior in everything in South Africa.”

Going into exile was ‘very hard’, but his treatment at the hands of the security services left him with few options. “I’d been held in solitary confinement on two different occasions. It is extremely punishing, you never get over it fully. The second detention involved sleep deprivation. I wasn’t strong enough to carry on. Looking back now I’ve no doubt I made the right decision.”

He initially came to England, spending 11 years studying and teaching law before travelling to Mozambique, where a black-led revolution had taken control. One wonders if, in the age of Brexit and right-wing populism, he still recognises the UK that accepted him in the 1960s. “I meet people in this country, and in the United States, who are appalled at what they see as a regression in terms of enlarging our humanity and finding that you enrich yourself through contact with others,” says Sachs.

“The Britain I love is the Britain that welcomed me – a refugee from South Africa – and the Britain that gave support to the anti-apartheid struggle. Diversity strengthens. The 2012 Olympic Games was fantastic – that was ‘great Britain’, it didn’t need a capital ‘G’. I meet many people in this country, and I know there are people all around the world, who feel the same way.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the 1980s Sachs worked closely with Oliver Tambo, head of the African National Congress. He was finally able to return to South Africa in 1990. Sachs could have been an ANC politician, but says he ‘never had ambition to exercise power’. Instead he accepted Mandela’s offer of a role in the courts in 1995, a year after South Africa’s first democratic elections. The justices’ first ruling led to the abolition of capital punishment and South Africa became one of the first places in the world to legalise same-sex marriage.

“Probably of all the judgments I’ve written that’s the one that’s best known. It’s remarkable how quickly society has evolved, although there’s still vicious repression of black lesbians in some very poor areas.”

He misses his judicial career ‘enormously’. “For the first year I got three honorary degrees, I had a book published, I got a medal in front of Barack Obama in Washington and I felt depressed. It took me a year to overcome. I found I could make mischief again in other ways.”

Sachs was closely involved in the development of the new constitutional court building, a place filled with contemporary artworks on the site of the Old Fort Prison where Mandela was incarcerated. “We’ve reconfigured what court buildings can be like,” he says. “It’s like the imaginative, rational and empathetic sides all connect up. I like to feel justice has to contain those ingredients in appropriate balance.”

Father’s connection to Yorkshire

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlbie Sachs has a strong Yorkshire connection – his father Solly stood as a Labour candidate in the Sheffield Hallam constituency after coming to England in the 1950s.

“He fought a terrific battle and he reduced the Tory majority from 21,000 to 19,000,” Albie recalls. “In other words they gave him a hopeless seat! It was different from London, there was a softness and a warmth – a closeness – that I remember to this day and associate with Sheffield.”

Sachs came to Sheffield as a guest of Baroness Helena Kennedy QC, the human rights lawyer who became Sheffield Hallam University’s chancellor last year.

Their friendship dates back to the 1970s when Sachs – an avowed feminist – wrote a book called Sexism and the Law.