Memoirs of a Dales lad doing a dangerous job

I never met my great uncle Dug, but I know just how he felt when he first went up in a balloon as a 19-year-old officer cadet with the Royal Flying Corps. I also know how he felt when he first saw the devastation of the Ypres Salient, parachuted from a burning balloon, advanced past dead comrades and ultimately celebrated the end of the war.

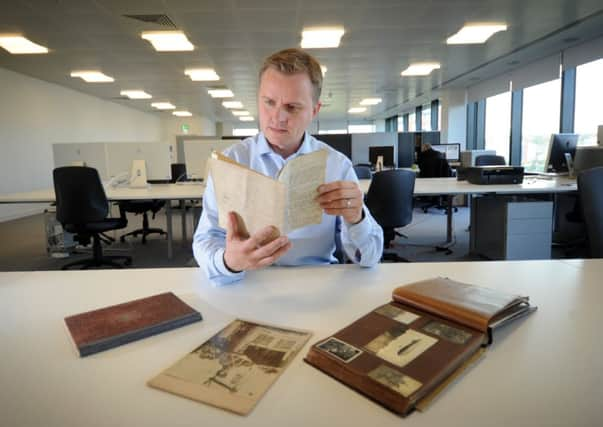

I know, not because I have any similar experience, but because I’ve read his account – 41 pencil-written pages of looping script in an old Northallerton Grammar School exercise book. It came to light recently, along with dozens of photos, at the back of a cupboard in my father’s house, and the timing could hardly have been more apt: one hundred years since the start of the First World War.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMatthew Douglas “Dug” Grainger was the eldest of four sons of a boot and clog maker in Hawes, Wensleydale. He had enlisted in June 1916 and after a spell in the Royal Fusiliers had been commissioned as a lieutenant in the RFC, but was assigned to balloons rather than planes, as he’d wanted.

“I will never forget the ‘nervy’ feeling I had when I stepped into the flimsy basket of a balloon,” he writes, and goes on to explain how much depended a companion’s demeanour on a flight; moods were infectious – “But I don’t think you will find many dull, low-spirited lads in the RFC.”

He would need to keep his spirits up. Before he’d even got to the Front his ship was attacked by a submarine, and there was worse – much worse – to come.

Posted to 36 Balloon Section, which consisted of six officers and 100 men, he found his work “extremely interesting”, but understatedly notes: “Our section was right in the point of the Ypres Salient – not a very healthy position, as we were continuously shelled from three sides. We had a marvellous view of miles of the Front and the scene of desolation is almost beyond description. When we reach-ed a good height we only had to turn away from the Front to see the English Channel and the cliffs of Dover.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe balloonist’s job was primarily to spot the positions of the enemy’s heavy guns, which made them a prime target – both for artillery and aircraft. As a result, balloon work was highly dangerous, and life expectancy was measured in weeks. Twice early on Dug was “sent down” when his balloon was hit by shell-fire, and in the following days and weeks he was bombed from the air, shelled from the ground and even gassed. But perhaps his closest brush with death came in September 1918, when when he was attacked by a German aircraft.

Spotting a “small red plane” gliding with its engine off, he watched as it flew overhead and then turned into the sun.

“Just before he turned towards me, I got out of the basket and hung on outside by my fingers, and watched him round the corner of the basket. He made a bee-line for the basket but he couldn’t see me as I had climbed over the side farthest away from him.

“After again passing the balloon, he zoomed upwards and then fired a short burst of tracer bullets through it. In a few seconds I saw a few wisps of smoke coming out of the ‘bag’, so I gave one backward heave and fell into space for about 300 feet, before I heard the welcome crack of my ‘Guardian Angel’ opening out above me. The German then dived and flew past me not more than 30 or 40 yards away. He raised his hand and I saluted him just to say I’m OK.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe most terrifying part of the episode, he writes, was passing through the hail of anti-aircraft shells and machine-gun bullets trying to bring the plane down. His luck held and he reached the ground safely, but not before his balloon – now “a mass of flames” – had passed him on the way down.

It was far from the last time he would be “sent down”, yet things didn’t all go the Germans’ way. Dug writes of the “fine feeling of satisfaction to see guns and ammunition dumps ‘going up’” after his own artillery had used his information.

Through October 1918, Dug’s section advanced rapidly over devastated territory, camping among dead Germans and passing dead Scots – “a terrible sight to see, holding their heads or clutching handfuls of grass”.

Eventually, deliverance came. The Armistice was signed when they were billeted in a recently-liberated château. The relief jumps off the page: “What a day! Needless to say, no work was done and in the evening we made a tremendous bonfire with a lot of German beds we found. We had a piano carried down into the barracks square, where the officers and men danced well into the morning. Aeroplanes were flying with their lamps alight and firing various coloured lights and rockets. It was a wonderful sight – never to be forgotten.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt all sounds extraordinary, and yet Dug’s experiences were far from unusual – even his escape from a burning balloon was an experience to be expected at least once by every “balloonatic”.

Not yet 21 when he was demobbed in Ripon in 1919, he went back to Hawes, where he married and took over the family business. It failed – after 150 years – and I can’t help wondering whether Dug’s heart was really in it. His collection of stories and photographs capture a youth in his prime, doing a job that demanded more skill, bravery and good humour, and offered more “nervy” moments, than anything Hawes had to offer. It can’t have been easy coming back down to earth after all that.

Perhaps more than anything else, the words and pictures he left us tell of a war that plucked young men from very ordinary homes and sent them to march towards guns or hurtle through smoke-filled skies, only to toss the lucky ones back to pick up the threads of their old lives.