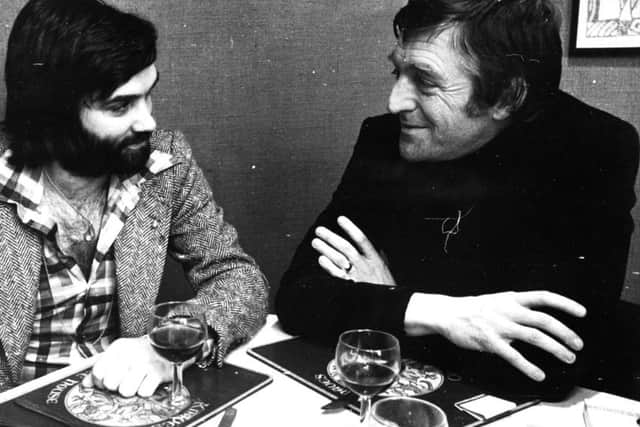

Sir Parky wants to chat about raising cancer awareness in Yorkshire

He’s had to contend with some recalcitrant TV guests over the years and survived an attack in the vitals by a certain emu, but arguably Sir Michael Parkinson’s biggest challenge has been his fight against cancer.

The Yorkshire-born broadcaster spent two years battling prostate cancer before doctors finally gave him the all clear last summer. It was a huge relief for Sir Parky and his family and when Yorkshire Cancer Research approached him about becoming its patron he was more than happy to oblige.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCancer death rates in this country have dropped 10 per cent in the past 10 years but it still remains one of our biggest killers, claiming more than 132,000 lives in England in 2013.

Last autumn, Yorkshire Cancer Research announced an ambitious strategy to invest £100m to tackle cancer inequalities in the region over the next decade, after revealing that people living in our region are more likely to get cancer, and more likely to die from it, than those living in most other areas of the country.

Yorkshire has the third highest cancer incidence rates in England and the charity’s goal is to ensure that at least 2,000 more people will survive the disease every year by 2025.

Speaking to The Yorkshire Post, Parkinson admits he was shocked when he was told about the disparities within parts of Yorkshire. “I had no idea they were so bad. It’s shocking to think this could happen in the county you were born in and which is known for its Yorkshire pride. We all know about social deprivation but you think ‘how has this been allowed to happen?’”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s why he’s determined to help the charity tackle these problems. “Having been diagnosed and treated for cancer myself, I understand how important it is to have access to the very best treatments and care. I believe that everyone should have an equal chance of living a long and healthy life,” he says.

“I was lucky to live in an area where early detection is commonplace but there are parts of Yorkshire where it’s not and that has to change. Early detection is incredibly important because if you get it early then most cancers can be handled, it’s not the death sentence it once was.”

When he was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2013, he admits it came as a shock. “It’s not like in the movies, you don’t faint. It’s more about ‘how can I deal with this?’ and the answer is by getting good doctors and good support and having the mindset that you’re going to get through this.”

Not that it was at all easy. “There are aspects that aren’t pleasant and you mustn’t hide that, the reaction to radiotherapy and chemotherapy. It’s not an experience I would wish on anyone but we’ve made advances in the treatment of most cancers,” he says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs well as supporting the charity he’s also on a mission to encourage more men to get checked for prostate cancer. “It’s about education. I was talking to Jonathan Agnew (cricket commentator) a little while back and I asked him if he’d been to get checked and he said ‘no’. So I told him he must go, and he did. It’s a simple blood test you just need to go to your doctor.”

The challenge now is to help the charity raise the money it needs to save more lives in the future. But at a time when the government is looking to tighten, rather than loosen, its purse strings, this won’t be an easy task. Which brings him to a topic that clearly bristles with him.

“What annoys me is this constant talk about the Northern Powerhouse. Leeds might be a good example, but Barnsley isn’t. They (politicians) should go there and see the amount of deprivation. Using such glib and misleading phrases really doesn’t help, it’s a cynical avoidance of reality.”

At, 81, the miner’s son from Barnsley has never been one to mince his words, a trait that has stood him in good stead during his career. A bright pupil, he attended Barnsley Grammar School and as a youngster he played cricket with Geoffrey Boycott and Dickie Bird and had trials for Yorkshire County Cricket Club.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut it was the clatter of typewriters on Fleet Street, rather than the sound of leather on willow, that beckoned for him. He started his career as a reporter on the South Yorkshire Times before heading to the Manchester Guardian and the Daily Express.

Then came television and before he knew it he had his own talk show. Parkinson ran for 11 years on the BBC until 1982 and returned in 1998 lasting for several years before Parky and his team moved across to ITV, finally calling it a day in 2007.

During this time he became the King of Saturday night telly. Bette Davis, Orson Welles, Jimmy Stewart, Cagney, Olivier, Burton... Parkinson worked his way through practically the whole panoply of major stars, slipping in some of his favourite jazz players along the way.

Today, Parkinson is held up as an exemplar of the talk show, something he feels has all but disappeared from our television screens. The show’s success, he says, was down to having what he calls “the great talkers”, people like Peter Ustinov, Jonathan Miller and Stephen Fry.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“They have this wonderful ability to make a joke out of anything and a keen eye for observation, they’re the kind of people you want on your show.”

When he was doing Parkinson he claims it wasn’t just a conveyor belt of people plugging their latest film or book. “We were allowed to cast our net wide, whereas nowadays you tend to see the same old people, usually comics. What you don’t see are these great talkers,” he says.

“The Graham Norton Show is very good and it’s well produced but I look in vain for any conversationalists. There’s no place for them in the modern scheme of TV. I don’t bemoan it I just worked in a different time,” he says.

“We’d have Billy Connolly and David Attenborough discussing issues and people like Dame Edna Everage. When I watch some of the old shows back with Dame Edna in it’s wonderful because I didn’t have to ask a question for ten minutes.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd this, he says, is what makes a good talk show. “You’re trying to create a situation where it becomes a conversation which is what a good interview should be.”

He’s rightly proud of the 700-odd chat shows he hosted over a period stretching almost 40 years. “I got to interview Bing Crosby, Fred Astaire, Paul McCartney, David Beckham and beautiful women like Lauren Bacall ... I’ve been very lucky.”

However, there were some famous names who he wasn’t able to interview, most notably Frank Sinatra. “He got away from almost everybody. He didn’t need any help to sell a book or a movie, he was on another level.”

There were some difficult interviewees, too. He had to deal with the prima donna behaviour of actress Meg Ryan who didn’t really want to talk and ignored the other guests, and a pair of actors who had smoked “something not sold at the tobacconists”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“You get some people who don’t want to do it for whatever reason and that’s where a different kind of expertise comes into play.”

As does the quality of your research, something he’s always been a stickler for. “You have to be certain in the knowledge that you’ve done everything possible to make it work. You only use ten per cent of your research but the rest is there so you don’t end up looking a berk.”

Over the years he became friends with many of those he interviewed but insists he never lost sight of his own role. “At the end of the day you’ve got to do your job properly because you aren’t the star, they are.”

Yorkshire’s fight against cancer

Yorkshire has the third highest cancer incidence rates in the country and last year Yorkshire Cancer Research launched a strategy to tackle cancer inequalities in the region by investing £100m over the next 10 years, with the aim of saving 2,000 lives every year in the county by 2025.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLung cancer is the most common cancer in Yorkshire, with incidence rates nearly 20 per cent higher than the national average. It is also the most common cause of death from cancer in the county.

According to the latest figures from Public Health England, more than 3,000 people in Yorkshire died from lung cancer in 2013, with the mortality rate in Hull almost twice the national average.

For more information about Yorkshire Cancer Research go to www.ycr.org.uk