Andrew Vine: Time to stop persecuting Armed Forces and respect their sacrifice in Iraq and Afghanistan

It was 2002, and British troops had secured the capital of Afghanistan after the Taliban were driven out.

Even so, the threat of ambush remained. And if Kabul was dangerous, the badlands beyond the city’s borders were even more hazardous.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAn uneasy peace just about held there, thanks to an accommodation with the ruling local warlords, but they were just as likely to side with the Taliban as with the international coalition attempting to liberate the country from tyranny and stop Afghanistan from continuing to incubate international terrorism.

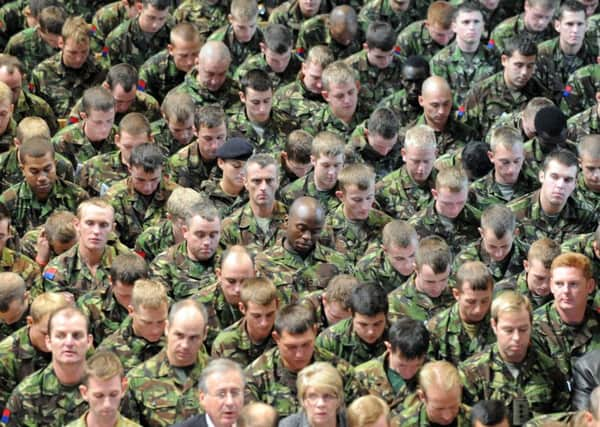

Danger and treachery were everywhere, yet the company of Royal Engineers I spent almost two weeks with faced them with undemonstrative bravery. Killings and maimings of British personnel happened with horrifying regularity, yet neither the engineers nor any of their comrades from other regiments flinched. Through it all, their overriding determination was to help the people of Afghanistan build a new future by driving out the fanatics who had inflicted such suffering on them.

But now, 14 years on, what thanks is Britain giving for their courage and compassion? What acknowledgement of the sacrifice of the 456 service personnel who died and the hundreds more wounded before that protracted, bloody mission was eventually over?

Shamefully, instead of thanks and acknowledgement, this country is redoubling its efforts to put troops who served in that murderous campaign not on the pedestal they deserve, but in the criminal dock. With a zeal that beggars belief, the Government is funding an expansion of an unnecessary investigation into allegations of abuse by British personnel in both Afghanistan and Iraq, at a cost likely to run into tens of millions of pounds.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAmong those making allegations is a Taliban bomb-maker convicted to 10 years imprisonment by the Afghan courts. He is claiming he was unlawfully detained by British forces.

The fact that he was kept locked up to prevent him attempting to kill our troops at a time when deaths from roadside bombs was reaching epidemic proportions seems not to matter. How bitter a pill to swallow this must be for veterans of Afghanistan. The bleatings of a convicted terrorist taken seriously and used in an attempt to make criminals of men trying to save their comrades’ lives.

Nor does it seem to matter that British taxpayers will fork out a fortune in legal costs to so-called human rights lawyers to pursue these claims through the courts.

Decorated soldiers are likely to be dragged into court on the flimsiest of evidence and, even if they are ultimately cleared, will have the shadow of having been put on trial hanging over them for life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis is not an exercise in justice or fairness, still less the righting of wrongs. It is an exercise in politically-correct vindictiveness that takes absolutely no account of the realities of fighting a war in which all traditional rules of engagement had to go out of the window.

Troops’ lives depended on split-second decisions and trying to anticipate threats. It was often impossible to distinguish between friend and enemy as Taliban fighters melted in and out of the civilian population.

To large swathes of the world, Britain must appear to have taken leave of its senses to be behaving like this. Operating alongside the British personnel, I was with were troops from Germany, Turkey and Italy. All faced similar risks, and had the same life-or-death decisions to make. Yet those three countries are not, a decade and more afterwards, doing their utmost to put their veterans of the fighting on trial.

And nor should we. What happened on the battlefield in the context of one of the most unpredictable and messy theatres of war in history must simply be accepted and acknowledged as having been necessary.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Government is making much of its credentials as being a new and forward-looking administration. It could take a significant step towards proving that by announcing an immediate end to what is no more than a persecution of Britain’s fighting forces over claims arising from both Afghanistan and Iraq.

Politely but firmly informing the human-rights industry that there will be no more funding for claims would lift a weight of worry and resentment from those who served, and have the physical or emotional scars to show for it.

Britain’s people showed their gratitude for the sacrifices of Afghanistan and Iraq in the crowds that lined the streets of Wootton Bassett as Union Jack-draped coffins that had been flown home.

They honoured the dead and their surviving comrades. Attempting to drag soldiers into court dishonours both the memory of the fallen and the service of the survivors.