The post of Christmases past

People have made predictions about the what the future may hold since time immemorial and while Christmas may seem a particularly apt time of year to make such declarations - as one year dies and another prepares to spring forth - it’s not often you come across a historical account which turns out to be all that accurate.

Such is the case, however, with our very own Yorkshire Evening Post’s annual yuletide supplement of 1934, otherwise known as the Christmas Number.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

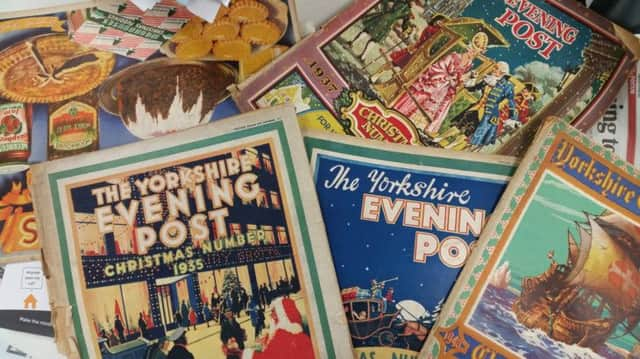

Hide AdAt a time when newspapers were still produced in black and white, these one-off supplements wore radiant full-colour jackets with cheerful Victorian-inspired painted scenes that spoke of romance, excitement, adventure and hinted at glowing fires in the snug confines of snow-bound homes.

They were packed full of rousing stories, recipes, trips down memory lane, puzzles, magic tricks and party games and were bedecked with a mesmerising array of advertisements selling everything from diamond rings to herbal tea.

In other ways, they show how times weren’t so different to today. There was an advert for Leeds Grand Theatre, which was showing Jack And Jill, starring comic heavyweight of the day Arthur Askey.

Nestled between a full page advert for Ovaltine - ‘everybody’s beverage for health this winter’ - and Barker’s Pianos, of Albion Place, Leeds (the cost of a Challen grand piano was stated as 65 guineas) was one such article.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEntitled What 2034 May Bring by Arthur Lamsley, it offered up a vision of what the future might hold and while some of it’s forecasts may have been a little bit (and a lot) wide of the mark, others were surprisingly accurate.

It begins: “A hundred years hence science will have given mankind wonders of material progress.” This may be something of a general statement but what follows is far more specific.

It goes on: “The family reunion… will be far more possible. Sons and daughters scattered all over the world will be able to go home for Christmas by a super air-liner and journey from the other side of the world in two days by travelling at the comparatively slow speed of only three-hundred miles an hour.

“Electricity a hundred years hence will contribute to the festive side of Christmas, especially for the young… it will revolutionise old forms of enjoyment.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Homely entertainments will all reveal the electric touch and the intriguing wonder of magic, so dear at this season to the young mind, will be made a thousand times more thrilling by the service of electricity.”

If one is not already put in mind of smartphones and computerised tablets, then this next sentence may well confirm it for you.

“A hundred years hence, through the aid of science, Christmas will even bring… through our more sensitive home wireless or universal telephone, which will have extended its area to other worlds of life.”

If only the author had known how prophetic his words were. For the ‘universal telephone’ as he calls it, sits at the centre of the digital revolution.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdStill, he was perhaps wide of the mark in predicting this would enable us to converse with the dead and to ‘listen in’ on historical events because, as he argues: “bearing in mind no sound is ever lost in space.” Unless, of course, that part has yet to come true also. The assumption seems to have been that at some point in the future, we will develop the ability to catch up with these leaked soundwaves and so glean from them valuable information about historic events. Time will tell whether this was mere fancy. The piece concludes, however, on a sentimental note: “If we were sure this would happen in a hundred years time - that at last generations to follow us would live in a world of goodwill and good neighbourhood, then science and its multifarious wonder would be amongst the most blessed gifts of Christmas.

“The idea of the first Christmas, to create a Christmas of humanity, is still a dream but science a hundred years hence has the power of turning it into a living reality.”

The adverts in these supplements also have a story to tell - they lack the gloss, the nod and wink of modern advertising campaigns, which, let’s face it can often seem irrelevant to the product being sold (examples abound: M&S, Sainsbury’s, John Lewis…) and yet they carry with them a sense of romance and warmth.

One, for Melbourne Ales proclaims its product is “beer brewed the good-old fashioned way, but under modern conditions”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAn advert for the Skipton Building Society describes the lender as a “snug sanctuary” and even lists its assets as £4m and reserve fund of £160,000.

It sits alongside adverts for cream from Provincial Dairies and antidepressant ‘Eezit’, which claims “depression will be banished by taking but one Eezit tablet.”

It adds: “Also for colds, flu and headaches.”

The old supplements yet have more treasure. While we may consider the ‘universal telephone’ and all it entails a distinctly modern invention, there is a pre-war equivalent which parallels the ‘text message’.

In the Christmas Number 1937, an article discussed the primitive (and incidentally wireless) form of mass broadcast - that of church bells, which had more uses than you might think. “Church bells,” it said, “were the first broadcast media, centuries before Marconi was born, to make the world one great sounding board. People who lived near abbey churches could always learn as much as was necessary from the air about the rhythmic strides of the enemy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The canonical hours observed by the monks were struck on the bells in the church tower. No licence was charged for this.

The curfew which “tolled the knell of the parting day” reminded people to put out their fires and say a prayer - a curfew bell was still sounded in 1937 in some Yorkshire villages. The summons of soldiers to arms to deal with emergencies was also communicated through the ringing of church bells.

The so-called pancake bell was also still sounded (in Holbeach, Lincolnshire) to remind people to go to confession before the season of Lent, while the ‘gleaning bell’ was always rung at the end of harvest - it took its name from the practise of a portion of harvested wheat being left for the poor to ‘glean’ or ‘gather’.

Another bell, called the ‘passing bell’ was rung in a village when someone was on the eve of death, while the ‘death knell’ was also still in use in some parts in 1937. Based upon the number of rings, listeners could determine if the deceased was a man or woman and from their local knowledge precisely who it was.