Rites of passage beneath the Pennines

It is no place to be if you feel claustrophobic. In front of the narrowboat, headlights reveal tight black walls and a low vaulted roof tapering to what seems like infinity. In places, hunks of rough-hewn rocks reach out as if to claw the craft’s hull but – inch by inch – more than 600ft beneath the Pennine heather the solid gritstone yields to the narrowboat’s intrusion.

“The first stretch is lined with bricks,” says pilot Terry Sigsworth, “but then we get to this long section of bare rock and that’s my favourite part of the entire tunnel. It gives me a strange sensation to think I’m looking at something hacked out by men 200-odd years ago using the most primitive of equipment.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere are 11 passengers, all in hard hats, making the three and a quarter mile trip through Standedge, Britain’s longest, highest and deepest canal tunnel and named as one of the Seven Wonders of the Waterways. To make the journey to the centre of the Pennines, a hike was first necessary across moorland from the Yorkshire entrance near the village of Marsden, at the top of the Colne Valley. This is the best way to appreciate just how vast an engineering project it was to bore a great hole from one side of England to the other.

Beyond the slate sheet of Brun Clough reservoir – a major source of leakages into Standedge – the path snakes down to a grid of emerald drystone-walled fields and the tunnel entrance at Diggle.

Once aboard the steel narrowboat, Terry addresses the passengers. “First off, let’s have some health and safety advice, because without it we’re all going nowhere. Top of the list is this. . . if you want to go outside on the boat, don’t do anything daft or I’m going to get picky about it. Don’t extend limbs outside the boat. We don’t want you to lose anything.”

The first thing to get used to is the loud and extremely monotonous beat of the engine. The noise is easier to tolerate, though, after Terry explains the traditional way of powering the craft through the Standedge would require passengers to take part in the practice of “legging”. That is, they would be asked to climb onto the highest part of the boat, lie on their backs and spend at least two hours pushing hard against the walls with their feet.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe second discomfort is the tunnel’s dank cold, which by the halfway point had penetrated every bone.

The journey felt longer than two hours, which was probably due to the lack of anything recognisable by which passengers could measure progress. Terry, on the other hand, knew the tunnel inside out you might say, and a series of underground features told him if he was keeping time, like those places where loose rock had been reinforced with steel mesh and sprayed with concrete, as well as the eight ventilation shafts, four passing places and two bends.

So improbable a feat does Standedge feel that no-one was surprised to learn that over 50 men were killed during its excavation, or that the original consortium went bust. When the project was eventually refinanced, yet more trouble loomed. The tunnelling that had been completed thus far – stretches on both the Yorkshire and Lancashire sides – was found to be higher at one end than the other. Major realignment work was necessary to make the two ends meet, and in the process there were serious roof-falls and more lengthy delays.

It is hard not to think of the men who planned Standedge as being anything other than bonkers. They were wealthy Northern industrialists to whom few people were prepared to say no. They wanted a new east-west route to carry their cloth and coal to ocean-going cargo ships at Liverpool docks, one that was shorter and quicker than the Leeds-Liverpool and Rochdale canals. Never mind that few major tunnels existed anywhere on earth. It would be another half a century before the British countryside thundered with the sound of dynamite blasting hundreds of miles of railway tunnels.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe techniques used at Standedge were primitive: just pick axes, small blasts of black gunpowder and something called a star drill, the crudest of all drills, requiring one man to hold it while another bashed it with a sledgehammer.

Not surprisingly the initial estimate of six years from the cutting of the first sod to the ceremonial ribbon-snip by top-hatted dignitaries turned out to be wildly optimistic. In the end, work on the Huddersfield Narrow Canal – as the complete route is known – took 17 years. Five or six of them passed with no work being done on the tunnel, and it was only saved by the hiring of Thomas Telford, the man who built the Caledonian Canal and the Menai Suspension Bridge.

Telford’s engineering plan for Standedge was so detailed that he estimated the work right down to the last bag of nails and the tunnel finally opened in 1811. It always struggled to make money, however, and the last commercial load passed through Standedge in 1921, leading to the eventual dereliction of the entire canal. Restoration began in the 1970s and work to make the tunnel navigable again was completed in 2001.

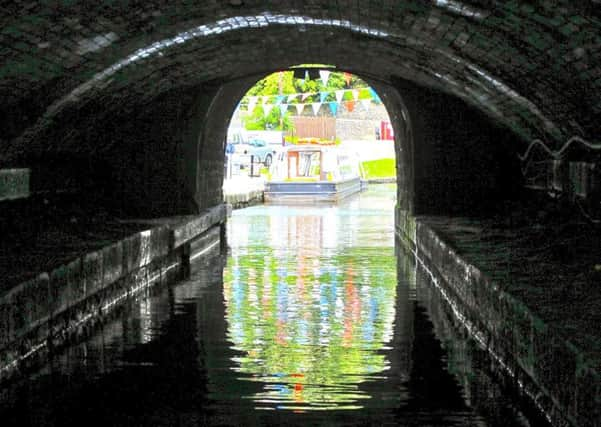

Back when the canal had been officially opened, the tunnel entrance at Marsden was surrounded by a crowd of 10,000 people and as the first narrowboat through Standedge came into view a brass band played Rule, Britannia! There were no strains of a band when our party finally saw a pinprick of light ahead and emerged blinking into the Marsden sunlight. Instead, we were greeted by sightseers taking photographs as if we were time travellers arriving back from 200 years ago.

• Trips through the tunnel (not suitable for under-sevens) run every other Saturday and must be pre-booked. 01484 844298, www.canalrivertrust.org.uk/standedge-tunnel