Tommy Taylor: The Busby Babe from Barnsley who supped pints with Dickie Bird

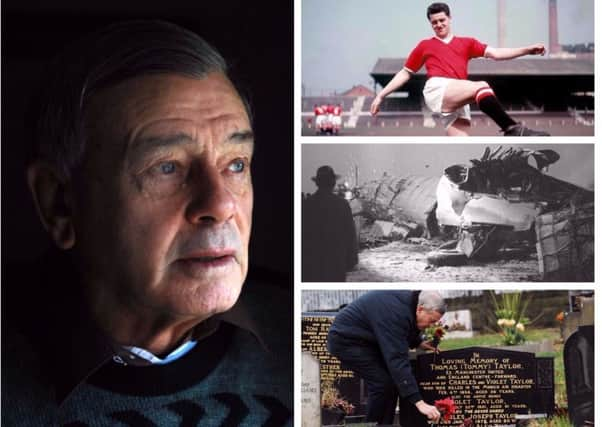

His childhood friend Tommy Taylor, a celebrated footballer from Barnsley, was among Manchester United’s fabled ‘Busby Babes’ to be killed in the tragedy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDavid Pegg and Mark Jones, also from South Yorkshire, perished in the disaster on February 6, 1958.

As commemorations are held to mark the tragedy, The Yorkshire Post republishes Bird’s emotive interview with comment editor Tom Richmond 10 years ago to mark the tragedy’s 50th anniversary – and what Taylor meant to his home town.

THERE was a spring in a young Harold Bird’s steps as he bounded home with his childhood friend Tommy Taylor, their faces lit up by the innocence of youth.

They’d spent the afternoon, just one of hundreds, playing football on a glass-strewn field in the shadow of their homes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMore to the point, a young Harold – universally known as Dickie – crossing the leather ball with precision for his pal to climb into the air and head into the net.

Both teenagers were invigorated as they walked to Dickie’s home for a glass of squash. Until, that is, they walked into the front door of his terrace home and saw the beady eyes of their respective coal-mining fathers waiting for them.

“I can remember it like yesterday,” Dickie says wistfully. “They sat us both down, we wondered what we had done wrong, and said forcefully that we would not be following them down the coal mine where they toiled.

“They said we were going to play sport for living, and that we would have to work damn hard.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe two boys were just 14 at the time. Dickie’s father, James Harold, and Tommy’s dad Charlie – Chuck to his friends – had clearly been plotting over a pint at The Woodman pub in Smithies, Barnsley, that was a corner kick away from the Taylors’ home.

Both miners – they worked on the same coal face at Monk Bretton Colliery – had remarkable foresight. One of the lads was destined to swap his football kit for cricket whites after injury struck and graduate to the Yorkshire first team before becoming the world’s most respected umpire.

The other was to become a legendary goalscorer for Barnsley before becoming one of the iconic “Busby Babes” who wore the evocative red of Manchester United.

Yet, while Dickie, to this day, remains an internationally recognisable figure, the great Tommy Taylor never had the chance to fulfil his limitless potential for club or country.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was one of 23 lives claimed on the harrowing and never-to-be-forgotten afternoon of February 6, 1958, when a plane carrying Manchester United home from a European Cup tie crashed on the snow-bound runway of Munich’s airport.

Eight of those were United players – the young “babes” whose flair was being nurtured by a pioneering Sir Matt Busby. They had the potential to become the greatest club side in history. An over-used adjective, the word “brilliant” fitted the Busby Babes.

“They tried three times to take off. Three times. They must have known there was a problem. Why didn’t anyone stop the plane? Why? Tell me, why?” implores Dickie, his eyes welling with emotion.

“Forget them having to come home to play a league game because the Football Association said so. Their safety was all that mattered.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe young sportsmen had become firm friends at Burton Road Primary School in Barnsley. Yet, ironically, it was, perhaps, one of the few schools in the South Yorkshire mining town that did not boast a sporting tradition.

Today, Dickie can still see the marks on the playground’s red-bricked walls which used to take a pounding from a leather ball at playtime. “Happy days,” he smiles. “And fun. We didn’t have all those silly health and safety rules in them days.”

Yet it was at Raley Secondary Modern where the sporting reputation of these two childhood pals became greatly enhanced. Even though he’s always been slight in stature, a young Dickie was captain of both the football and cricket teams. He also earned a place in the Barnsley Boys team.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs an inside forward, he passed the ball with slide-rule accuracy for his lightning quick friend to latch onto and power into the back of the net. Unlike Dickie, his friend also had great presence in the air; his six-foot plus frame proving to be a wonderful asset.

“I remember one of our teachers Arthur Hudson, who we called Pop. He gathered us altogether for a game and asked if we had our kit. This would have been just after the war.

“Tommy put his hand up and said, ‘Sir, I’ve only got my clogs. I haven’t any boots’. Times were hard, his family couldn’t afford any boots and he was told he couldn’t play until he had found some.

“It’s one of the reasons why I set up the Dickie Bird Foundation to help under-privileged children. These were tough times. I want to help children have a chance to pursue their sporting dreams.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Unless you get that chance, you don’t know how good you can become. I always think of that conversation between Pop and Tommy. It’s what motivates me. We have to give young people a chance.”

In today’s era, where hi-tech gadgetry has become the primary form of entertainment of most children, there is something quietly nostalgic when the retired umpire speaks with such passion about his childhood – and the values that he and his contemporaries learned.

“Tommy and I used to practise on very rough ground. There would be broken glass and rubble everywhere, but that didn’t stop us. We practised for the love of the game,” recalled Dickie.

“I would float the ball across and he would head it. To me, Tommy Taylor remains the finest header of a ball that I have ever seen. The finest. I like to think I may just have played a small part in his development.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“He had the gift of being able to rise in the air and hang there, waiting for the ball to come to him and then heading it with tremendous power. And nor was it heading the plastic-coated balls of today. This was a heavy leather thing, with the bladder sticking out in a large blob where the stitching had burst. We couldn’t afford a new one.

“When we played with the rest of the lads, it was usually 38-a-side on a strip 30 yards long. Chaos. It was a case of ‘next goal wins’ when it got dark. And it was usually Tommy who won us the game.

“There was none of today’s players who can only play with one foot. Tommy was two-footed. He had it all. And he got it from playing every day after school. That’s what we did in them days. Stayed out of trouble, went to church on a Sunday and got on with our lives.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

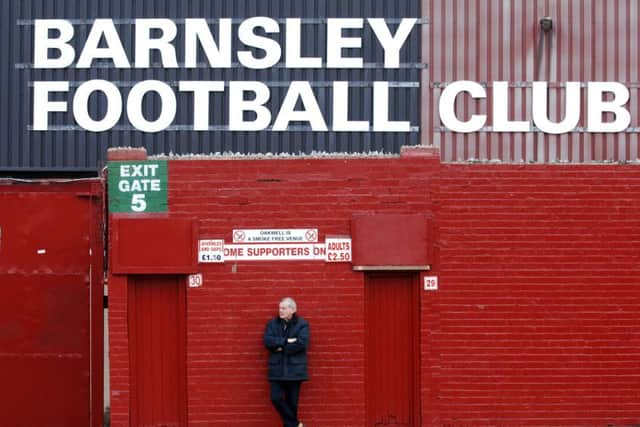

Hide AdIt was inevitable, with such dedication, that both boys would sign amateur forms with Barnsley Football Club – Dickie even harboured dreams of playing both football and cricket for his country.

That was until he wrecked his knee in a tackle as a 15-year-old, an injury that has subsequently required five operations. He has not kicked a ball since.

He became spellbound by his friend’s progress as Tommy scored a phenomenal 28 goals in 46 appearances for Barnsley from 1950-53 before joining Manchester United where he netted 128 times in 189 games.

“Do you know? He never wanted to sign for Manchester United, did Tommy,” recalled Dickie.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It was only because Barnsley needed the money. I think you’ll find that Sir Matt Busby and Jimmy Murphy concluded the transfer in the cinema because they wanted to keep it secret.

“They also agreed a fee of £29,999, so he didn’t become burdened by the tag of becoming the country’s first £30,000 player.

“He may have shared digs with the likes of Bobby Charlton, but the fame did not change him. He always came home after a game and supped a pint in The Woodman. You used to in those days; players were close to their roots. Not now.

“When I played cricket at Old Trafford, he came and sat in the crowd. His digs were in one of the terraces close to the ground. Tommy would come after training. How many players would do that today?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“And Busby rated him. I talked to Sir Matt at the cricket after Munich. ‘Dickie’ , he said. ‘Your friend was a great player’.

“To me, you couldn’t have asked for a higher compliment from a higher man. That said it all. Tommy Taylor was the humblest of the very humblest, a gentle giant.”

Dickie Bird is quietly standing in Monk Bretton Cemetery, his head bowed, at the spot where virtually a whole town turned out in February 1958 to lay to rest one of its greatest heroes.

“Come to see your friend Tommy?” a lady tending a neighbouring grave asks. “Fifty years he’s been gone,” he tells her. She nods her head in quiet acknowledgment.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPerched on the brow of the hill, the wind whistles past as he quietly rearranges a Barnsley United scarf left on the grave by a well-wisher.

“Gone but not forgotten, my friend,” Dickie whispered as he examined the wording on the gravestone.

The symbolic football that once stood on the grave, and was targeted by vandals, has been replaced by a modern gravestone that honours Tommy and his parents.

A small bunch of flowers – predictably red in colour – lies on top of the scarf.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe cemetery is hauntingly silent as Dickie reads the headstone’s beautifully simple words: “In loving memory of Thomas (Tommy) Taylor, Ex Manchester United and England centre-forward – son of Charles and Violet Taylor – who was killed in the Munich Air Disaster, February 6th, 1958, Aged 26 years.”

“Did you know that the family could not say goodbye to Tommy? All that came back were ashes in this large German coffin. Ashes. That was all that was left of him,” says Dickie as the tears start to flow.

He regrets that he does not have a photograph of himself with Tommy because, they believed, that there would always be time and that they would never be separated.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It’ s heartbreaking to think what might have been. For Manchester United. For England. And for Tommy Taylor.”

The footballer was so revered that his young team-mate Nobby Stiles, who became a World Cup winner in 1966, asked to keep Taylor’s boots.

As Dickie Bird ponders England’s struggles in World Cups and other major tournaments, he wistfully muses what his friend would be worth in today’s market.

“Millions. Sixteen goals in 19 games for his country. He’d be worth millions – tens of millions of pounds. Do you know what? I don’t think he had even reached his prime when his life was taken.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere is a pause as Dickie struggles to contain his emotion. And then he points at me: “I’ll tell you what. Tommy Taylor would be priceless today as a player and as a person. He would have broken all records for goal-scoring. He was better than Geoff Hurst who scored three goals in the 1966 World Cup final.

“Priceless, that’s the word. Priceless.”

Read more: