On top of the world

Edward (Teddy) Norton was not a man to push himself forward, although 90 years ago he very nearly made it to the top of the world. A multi-talented soldier, he was the leader of the 1924 Everest expedition which included George Leigh Mallory and Andrew (Sandy) Irvine, the climbers who vanished close to the summit, creating one of the great adventure mysteries of modern times.

Setting out from Darjeeling at the end of March 1924, the 12 climbers and their entourage reached base camp by the end of April. The British were the first to try to conquer Everest and this was the third expedition they had sent out in four years. National pride – thwarted in the race to be the first to reach the north and the south poles – plus the expectations of the Empire were riding on a successful outcome.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs May turned into June, the team was poised towards the top of the mountain and the fittest candidates were paired-up with a view to them making separate attempts on the summit from the final staging point of Camp VI.

Mallory, the star performer, was the first to go, accompanied by Geoffrey Bruce, on June 1. But wind and the reluctance of their porters to go further, obliged them to descend the next day. Approaching Camp IV on the way down, they passed the second pair, Edward Norton with Dr Howard Somervell, on the way up.

An infected throat hampered Somervell as the two set out from camp VI at for the summit at 6.40am the next day, June 4. His sickness worsened and after six hours he was so ill, Norton said he thought his companion was going to peg out.

He pressed on solo – and without oxygen – to 28,120ft. The summit stood tantalisingly close, a few hundred feet away. He had set a world record for altitude climbing without oxygen for someone who would live to tell the tale which was to last for over half a century. But the expedition leader could drag his exhausted body no higher and also turned back.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMallory, having climbed down to Camp III, chose another partner, Sandy Irvine, for his second try. Equipped with oxygen this time, they made their way to Camp VI and set out to grasp the ultimate prize early on June 8.

Norton was crippled by painful snow blindness (“stone blind” in his own words) after his own titanic effort, could see nothing. For the others below, swirling mist obscured the summit, although one of them, Noel Odell, later reported seeing Mallory and Irvine through a telescope “going strong”. The mist closed in, time passed. Later in the day a fierce snow squall came on. The rest was silence.

In his diary the next day Norton wrote, “Rough, cold day – very stormy high wind on mountain.” His painful blindness had eased and he spent the whole day with the others anxiously scanning the mountain and Camps IV and V. Finally he wrote. “By 11.10 decided disaster was probable…” He sent out a letter to the team containing four instructions. The third one reads, “Principle (the word is underlined) to risk no more lives in trying to retrieve the inevitable… By now it appears almost inevitable that disaster has overtaken poor gallant Mallory and Irvine – 10 to 1 they have ‘fallen off’ high up…”

Mallory’s body, preserved by the conditions, was eventually discovered in 1999, giving new worldwide impetus to the mystery. Irvine’s has never been found. Were they perhaps the first conquerors of Everest, but perished on the way down?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

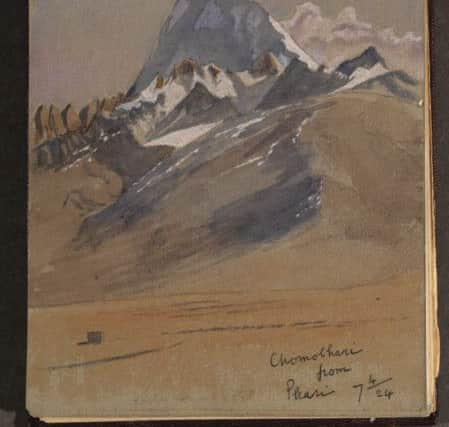

Hide AdIt’s an epic tale and the expedition’s leader produced a vivid first-hand written and visual account of it in diary entries and accomplished watercolour paintings. He also made a series of 10 lively and humorous pencil sketches of his companions. Rather than present them as action heroes, he sometimes depicts them as mild eccentrics, reading the Times Literary Supplement or posing with a brolly.

Edward Norton kept this material private and it has not been seen by the general public, until now. His grandson, Christopher Norton, a semi-retired academic at York University, has put together a book from this treasure trove.

“My grandfather was a modest man,” says Christopher. “He never made much of his achievement and he thought that the diaries, sketches and watercolours were of no interest to anybody. My grandmother kept them, only for the family to look at. I think he had this Victorian idea that a sketch was not a finished work or art, where today we appreciate the freshness of something that’s been done on the spot. The idea for a book germinated in the family and we thought the time had come with this being the 90th anniversary.

“At the time, grandfather didn’t publicly express an opinion on whether Mallory and Irvine got to the top, so as not to cause more grief for the families. Keep your team alive – that was the most important thing for him. He had applied to go with Ernest Shackleton to the Antarctic and he saw Shackleton as the model to follow as a leader. Everything must be done to get everyone back off the mountain alive. He was very distressed that he didn’t manage that.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEdward Norton had learnt his rock climbing in the Alps and his leadership potential was quickly spotted by the Army during a career which started more than a decade before the First World War began. When it ended, he was commander of a battery of Royal Horse Artillery, having been mentioned three times in dispatches and awarded a DSO and the MC.

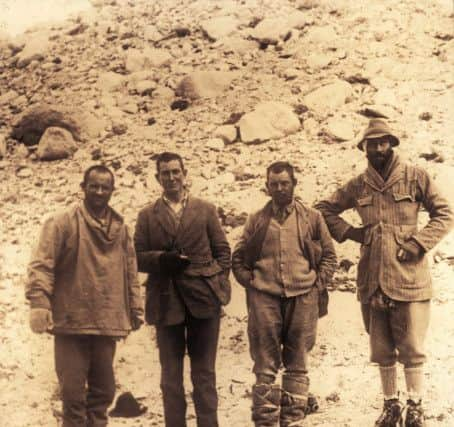

Soldiers made up half of the team selected for the 1924 Everest expedition. Others, including school teacher Mallory, had also served on the Western Front. Fresh memories of years of slaughter must have coloured their outlook. Whether any of them were driven to push themselves to the limit and beyond on Everest by the modern notion of “survivor guilt”, as some suggest, is speculation.

It seems more likely the scale of the extreme challenge and how to survive it wholly absorbed their minds. It was Mallory, who when asked why he wanted to climb Everest, came up with the line, “because it’s there”.

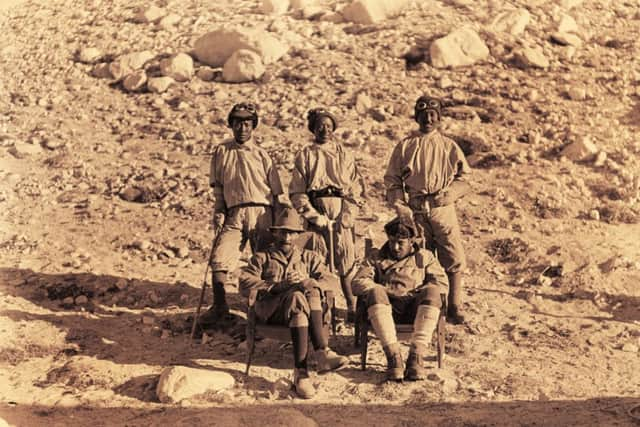

Strictly speaking they were amateurs – the expedition was privately organised and funded by the members of the Alpine Club and the Royal Geographic Society. But these were men of influence who knew the right people, in some respects they were a contingent of the British Establishment in big boots and goggles. Norton also found time to send back specimens of birds and flowers to the natural history section at the British Museum. Like him, the others were multi-talented individuals, soldiers as well as expert surveyors, geologists, naturalists.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“They were all extraordinary men – not just tough,” says Christopher Norton. “It was a real scientific expedition. They had a physiologist whose job was to study acclimatisation. Could men even survive at 27,000ft? It was thought that anyone who crawled into a tent at night at these heights would be dead by morning.”

His grandfather had already made one attempt on Everest with the 1922 expedition. He must have been an obvious selection. In addition to his tact and an admirably collegiate approach to leadership, he knew India well from his army postings. And to top it off, he was a superb climber. His grandfather, the founder of the Alpine Club, had built a family chalet in the Alps where Edward honed his skills whenever he had the time.

“He was not obsessed with knocking off summits,” says Christopher. “After 1924 my grandfather went back to climbing from the family chalet. Part of the deal for the 1924 expedition was for the leader to write 15 exclusive despatches for The Times newspaper. He didn’t like that at all. He did not have a Himalayan obsession. It was just something he did and then he carried on with the rest of his life.”

A richly varied career concluded with a posting as acting governor and commander-in-chief in wartime Hong Kong. An injury from a fall caused him to be invalided back to England in 1942 shortly before the Japanese invasion. After the war, Sir John Hunt approached him for advice as the 1953 Everest expedition was being readied and after his triumphant return Hunt wrote, “to you goes a big share in the glory”. Edward Norton died the following year. Of his three sons, one inherited the adventure gene – Christopher’s uncle Bill, who is now in his 80s and still mountaineering. By a quirk of fate, Bill was on a Himalayan trip when he bumped into a 97-year-old retired sherpa who turned out to have been a porter on the 1924 expedition.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe old man explained that when they had sought the blessing of an important local priest for the ascent, the sherpas were told to provide all the assistance asked for, but not sufficient for the Englishmen to conquer Everest. The gods would be angry if they did.

It’s all credit to Edward Norton’s leadership that he could persuade such deeply pious men, to keep going upwards against the wishes of their holy man. Few can have fitted the template of an English hero so comfortably as Edward Norton. His story is a reminder that modesty and understatement were once valued qualities.

An Everest climb is now a holiday commodity. The cost of ascending Everest, as Norton did from the Tibetan side, is about £18,400. The price includes meals, climb leader, yak transport and equipment. By all accounts it comes with the attendant problems of litter, detritus and queues.

At home in York, Christopher Norton has a little Tibetan dog, a lhasa apso. It’s his closest association with the Himalayas. There are large paintings of mountain scenes on his walls but real peaks have never really been his thing. “I liked walking in the mountains, but I’ve never felt the desire to do any rock climbing,” he says. “The Lake District was about right for me.”

• Everest Revealed: The private diaries of Edward Norton 1922-24. Edited by Christopher Norton. The History Press, £20.