Woman’s hidden war diary is set for the screen

And now, the remarkable life of Madeleine Blaess is set to be transformed into a documentary film for the first time, after her unpublished diary was found hidden under her bed.

The Sheffield University team behind the project is set to begin filming this month, and the documentary is scheduled for completion next summer.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“She was an extraordinary woman”, said Dr Wendy Michallat from the department of French at Sheffield University, who is leading the project.

“For a woman to pursue a career in those days, let alone an academic career, was really quite something. She was quite a feisty character.”

Miss Blaess was born in France but her family moved to York, where her father worked in a hotel, while she was an infant.

After graduating from Leeds University in 1939, she travelled to France to begin a doctorate, but found herself trapped by the German advance in 1940.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

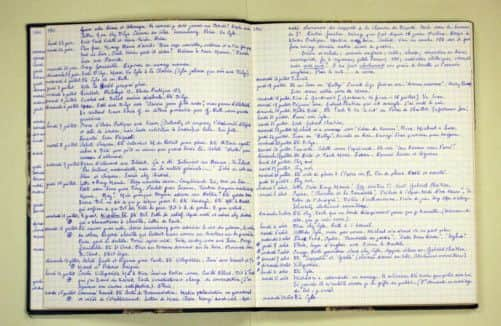

Hide AdMiss Blaess began her diary in October 1940, continuing to write it with barely a missed entry until October 1944.

She went on to become a lecturer within Sheffield University’s French department from 1948, until she retired in 1983.

Now, the manuscript of the diary is set to be transformed into a documentary film about Miss Blaess’s life in Paris under the German occupation.

Dr Michallat said: “The diary contains unprecedented detail about everyday life in wartime Paris and its crushing isolation, desperate shortages, horrific repression and persecution.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It also details Madeleine’s resistance activities and her friendship with fellow student Hélène Berr, deported and murdered by the Nazis and whose own diary was published posthumously in 2008.

“This and the fact that Madeleine enjoyed a rich cultural life by way of her friendship with Sylvia Beach and her literary circle make this a unique manuscript with exciting narrative possibilities.”

In December 1940, three months into the diary, Miss Blaess records the arrest and internment of her flatmate, friend and fellow student, Ruth.

It is an event that shocks her into being more circumspect about explicitly detailing her views on the war for fear that the diary would be found.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShe imposes a shorthand of hints and abbreviations and a preponderance of proper names which, although devoid of explicatory context, have through research proved to have been contacts in the French Resistance.

Miss Blaess’s diary begins as a letter to her parents, to replace the letters she is no longer able to send them.

That she writes the diary in French is logical given that her parents are French, said Dr Michallat.

However, she added, it could also have been a self-preservation strategy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“She had French nationality, which was the technicality which saved her from arrest, but she was always fearful of being arrested because she was to all intents and purposes British”, she said.

“This is probably one of the reasons she wrote the diaries in French, so if it was found she could pass herseulf off as French.”

The diary is a desperate record of Miss Blaess’s struggle to survive isolation and depression as well as chronic food shortages, bombing raids and the ever-present spectre of the Nazi threat.

The arrest of British, American and Canadian and, later, French Jewish friends make her fear for her own fate but her most pressing fight is to stave off the malnutrition that is causing the illness and, tragically, the death of many of her young friends.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter the war Blaess eventually managed to return to her parents in Yorkshire and in 1948 she realised her ambition of an academic career, obtaining a post lecturing in Sheffield University’s French department.

In 1983 she retired and, in 2003, she died, bequeathing her books and papers to the university.

It is only now, however, that the hidden diary is being transcribed and translated.