Would you want to live to 100?

MARK Twain once quipped that age is just a case of mind over matter – “if you don’t mind, it doesn’t matter.”

He died just over a century ago when life expectancy was much shorter than it is now. In 1918, boys in Britain could expect to live until they were just 44.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s a far different picture today when around one in five people alive in the UK are expected to reach 100. Improvements in medicine, healthcare and diet have transformed life expectancy figures not just in our country but around the world. The number of people aged 60 and over has doubled since 1980, with the figure predicted to reach two billion by 2050.

But while we ought to be celebrating the fact that we’re able to live longer there are several ominous-looking clouds on the horizon. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the number of older people unable to look after themselves in developing countries is forecast to quadruple within the next 40 years, and the question of who pays for the burgeoning cost of long-term care of the elderly has become a political hot potato.

Then there’s the growing spectre of dementia with more than 820,000 people in the UK battling with the disease, a figure that is rising all the time.

So despite all the advances in medicine and technology there is a creeping fear about what lies in wait for us a few years down the road.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut while there are no shortage of challenges facing us as we grow older it doesn’t have to be a grim process of decline and decay. There are plenty of people who are defying the ageing process – people like Olga Kotelko. Earlier this year, the 95 year-old became the oldest recorded female indoor sprinter, high jumper, long jumper and triple jumper at the World Masters Athletics Championships. Not bad for someone who took up athletics at the age of 77.

While Olga might be more of an exception than the norm research increasingly suggests that for many of us the genetic hand we are dealt at birth accounts for only a quarter of what determines how long we live. This means that we might have a bigger influence on what happens to us in later life than we perhaps realise.

Lifestyle, of course, has a big part to play and the importance of a healthy diet and regular exercise is constantly drummed into us. We all get older, it’s a fact of life, but can our attitude to life affect the way we age?

Harry Smith is a 91 year-old Second World War veteran originally from South Yorkshire and now living in Canada. He taught himself how to use computers in his mid-80s and has embraced social networking sites like Twitter and Facebook as a way of engaging with a younger audience. I caught up with him last month in Bradford during a fleeting visit to promote his new book Harry’s Last Stand – an impassioned plea to the next generation not to squander the freedoms that his generation fought so hard to protect.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI met someone who refuses to be bowed by old age. “I never accepted the fact that I was getting old. When I was 80 and still living in my own house I ordered 15 tons of gravel and I spread it myself with a wheelbarrow and a shovel, “ he told me.

“My son came to help me and he pushed one wheelbarrow load and that was it, he couldn’t do any more – but I could. You just have to beat the odds.”

Jack Barstow, from Leeds, is among those who has defied the odds. I had the pleasure of interviewing him two years ago shortly before his 100th birthday. Not only could he have passed for someone 20 years younger he was still playing snooker and crown green bowls and had gained a reputation for fixing broken clocks, with people coming from across Yorkshire to get them repaired.

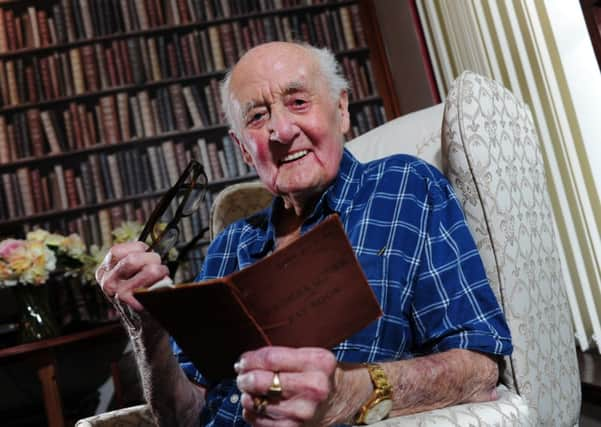

Jack is one of more than 12,000 people in the UK over the age of 100 and this week Harold Wilcockson joined this growing band of centenarians. He now lives in a care home in Harrogate but hasn’t lost his zest for life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I don’t feel like I’m a hundred, I feel 70. I’ve got everything up here,” he says, pointing to his head. He’s not even the oldest person in the care home. “We have a lady here who’s 102 and she’s doing all right,” he says.

Harold was born at Shaw Mills, near Harrogate, a month before the start of the First World War, in the same year as Alec Guinness and Dylan Thomas. His memory is astonishing and he reels off the places where his parents lived, along with the names of schoolteachers and the family that gave him his first job more than 85 years ago.

He remembers leaving school shortly before his 14th birthday and going to work for a local poultry farmer called Mr Abrahams. He later became a gardener in Harrogate earning 9d (pence) an hour. “I cycled to work every day, six miles there and six miles back,” he says.

It’s often assumed that our memories inevitably get worse with age, but research carried out by Professor Ian Deary at Edinburgh University suggests that isn’t necessarily the case. Some parts of our memory can actually get better with age, so our memory banks for general knowledge and vocabulary have the potential to improve over time.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLike many of his generation, Harold joined the army during the Second World War, becoming a tank wireless operator. He took part in the North Africa Campaign and experienced the harsh realities of desert warfare. “The nights were very cold and you needed all the clothes you could get around you. But the days were hot – hot enough to fry an egg on the mudguard.”

He fought at the Battle of El Alamein in 1942, which proved to be a turning point in the gruelling war against Rommel and helped restore British morale. He recalls meeting General Montgomery the night before the battle. “He came to see us in his staff car. He went round his troops and I shook hands with him, what a marvellous man he was.”

Harold’s wartime exploits also took him to Sicily and Naples and later the beaches of Normandy in 1944, before he was invalided out of the army after suffering perforated eardrums.

“It’s hard when you’re in a tank for twenty hours a day and you have the earphones on so tight you can’t hear any outside noises, so I put it down to that. I would have liked to have gone on to Germany but it wasn’t to be.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe returned to England and was demobbed at the end of the war. He and his beloved wife, Margaret, had two sons and the couple remained together until she passed away in 2009.

Although he “retired” 38 years ago at the age of 62, Harold, now a great-grandfather, continues to keep active and although he’s a little unsteady on his feet these days his mind remains agile.

As for the secret to his longevity, he puts it down to laughing and enjoying the odd tipple. “I like to have a laugh and a joke. We have a writing club and we write stories and raise money for a local hospice selling magazines with our stories in,” he says.

“I enjoy having a sherry and when I go down for dinner I have red wine ... that’s doctor’s orders,” he adds, with a mischievous chuckle.

Well, who are we to argue?