The Yorkshire artist and printmaker celebrating a double first

Ed Kluz is clearly an architect manqué and that’s a tragedy for the built environment, which could have benefited greatly from his originality and imagination. Still, he has no regrets about putting his talent for drawing, attention to detail and obsession with buildings to another use. Designing and constructing properties on paper has ensured that they are always feted and free from censure by planning officials and Nimbys.

“Architecture is the core of my work and I’ve been interested in it for as long as I can remember,” says the Richmond-based artist, illustrator and printmaker, who is celebrating his largest solo exhibition to date and his debut book.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

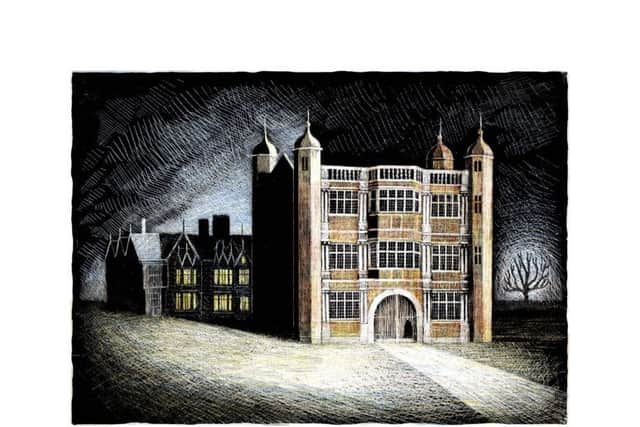

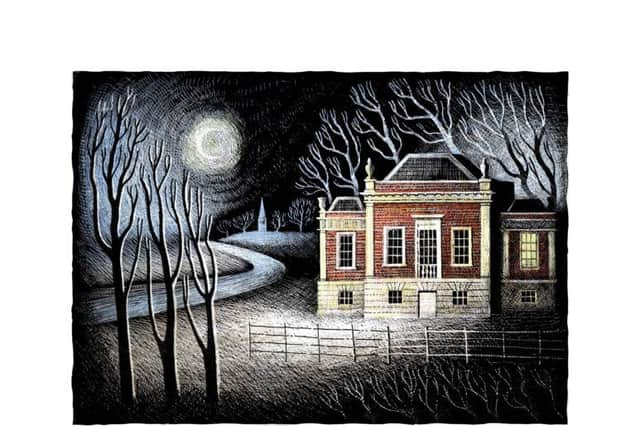

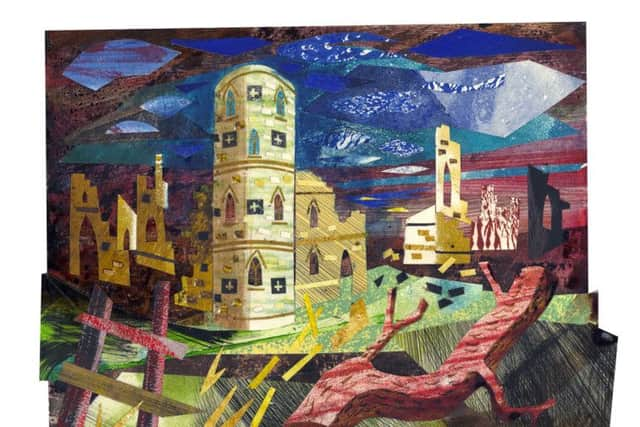

Hide AdThis month the Yorkshire Sculpture Park presents Sheer Folly – Fanciful Buildings of Britain, which sees Ed celebrate the often overlooked follies that add character and an element of surprise to the British landscape. The exhibition runs from November 11 to February 25 and includes original paper collages, scraper boards and prints, all imbued with the atmosphere and otherworldliness that the artist is renowned for.

The collection, described as “vibrant, meticulous and sometimes dark”, includes some of his favourite Yorkshire follies. The grand Temple of the Four Winds at Castle Howard was an obvious choice. Designed in 1724 by Vanbrugh, it is modelled in part on Andrea Palladio’s 16th century Villa Rotonda in Vicenza.

The quirky Ruin at Hackfall, also from the Georgian era when folly construction was at its peak, was another must-have. It is a bizarre concoction of a Gothic frontage with a Romanesque ruin at the rear. Once used as a mini banqueting house, it was restored by the Landmark Trust and is now a holiday let.

“One of the things I love about follies is that they are so peculiar and imaginative. It’s architecture that exists to amuse,” says Klux, 37, who has also made a limited-edition print of the Belle Vista tower that once stood in the grounds of Bretton Hall, now home to the Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBelle Vista tapped into his long-held fascination for buildings that have been lost. “The allure of the long gone is a powerful attraction for me and the unseen sparks my imagination far more than the seen,” he says.

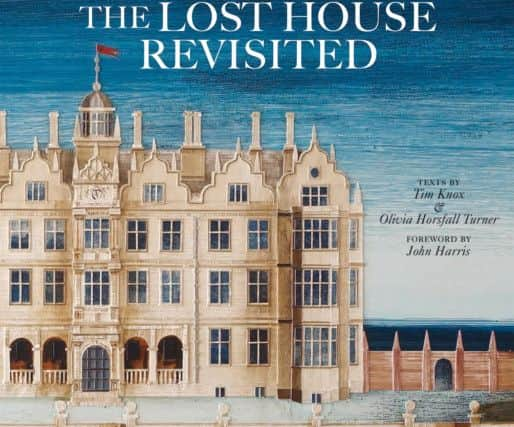

Nine grand English houses that were abandoned to ruin, burned down or deliberately destroyed are the main subjects of his first book, The Lost House Revisited. In his introduction, art and architectural historian Tim Knox describes Kluz’s distinctive collages as “heirs to the highly-perspective drawings of architectural artists in centuries past” and draws parallels with the bold graphic tradition of Eric Ravilious and Edward Bawden.

Each of the properties is introduced by historian Olivia Horsfall Turner who details its life and its fate. They include medieval Worksop Manor in Nottinghamshire, which was destroyed by fire in 1761 and the short-lived Hope End in Herefordshire, 1809-1873, the childhood home of poet Elizabeth Barrett-Browning. It was flattened to make way for a bigger modern mansion.

Rather than a strictly accurate recreation, Kluz says: “I have chosen to show the houses more like ghosts, existing in surreal, dreamlike landscapes illuminated by theatrical lighting. They conjure up the vanished buildings in all their pomp, captured on the verge of dissolution.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis research included studying old engravings, floorplans and descriptions and he compares the act of making the collages to that of model-making, with each architectural element drawn and then cut from paper and pasted, layer upon layer, on a background of inks to give a textural 3D effect.

None of his houses feature a landscaped setting as he believes that a “stripped-back, starker setting, brutal and minimal, allows the architecture to speak for itself”.

The book is dedicated to his mother, a florist, and his father Andy, a former Tyne Tees TV presenter. They encouraged his gift and got him hooked on historic buildings. He recalls his father describing his own childhood home, Kingsley House in Stamford. In poor condition with a semi-ruined wing dating to the Norman Conquest, its rooms, grounds and resident ghost featured heavily in his father’s stories.

When Kluz was a small child, his parents bought a derelict 18th century farmhouse in Applegarth in Swaledale. The family lived in a caravan for two years while the renovations were ongoing.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“That process of putting a house back together inspired me and my parents were always dragging us round museums and country houses,” says Kluz, the eldest of three siblings.

Also credited with feeding his preoccupation with historic homes are the 1970 film The Amazing Mr Blunden, about children who become custodians of a dilapidated country house, Edward Waterson’s Lost Houses of Yorkshire, Janette Ray of the Rare and Out of Print bookshop in York, who introduced him to the catalogue for The Destruction of the Country House exhibition at the V&A in 1974, and his sixth form art teacher Chris Moss. Moss often took his pupils into the grounds of St Nicholas House in Richmond to draw the topiary gardens. “Chris was hugely formative,” says Kluz, who went on to study at Winchester School of Art.

The V&A, Faber & Faber, Folio Society, John Murray publishers and Little Toller Books are among his commercial clients. He is also a member of the St Jude’s group of printmakers.

Chris has lived in various places but, for now, his studio is the attic of an old house in Richmond, where he works from 8.30am till 7pm before tackling admin. He is also part of a project in Reeth to capture the memories of older Dales residents and would like to do a series of books on houses by lesser-known architects, such as John Thorpe and Balthazar Gerbier, and is already planning to resurrect more lost houses.

“It’s something I will always be interested in,” he says. “I enjoy the creative reimagining, the challenge of a putting the puzzle together to get a sense of what the houses were like.”