Yorkshire '˜creamware' that graced middle-class sideboards of generations past is dusted off once more

The earthenware dinner sets they turned out were more Woolworths than Wedgwood, but they were a fixture on the sideboards of middle-class homes across the county for generations.

Most were broken up long ago, but a few surviving relics of the fashion for so-called creamware – plain pots that would serve as status symbols as readily as they could serve salad – are now being dusted off for a new exhibition.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe display, and the story of the region’s crockery heritage, has been pieced together by MA students at Leeds University learning the art of museum curation.

The pots would have served originally as the “best china” in households that would not have aspired to Royal Doulton but whose occupants could nevertheless splash out on small luxuries, said Beth Arscott, one of the trainee curators.

The old plates, cups and “bon bon bowls”, dating from the 1760s to the late 19th century, were handed down through the generations and can still be found in the display cabinets of traditional Yorkshire homes.

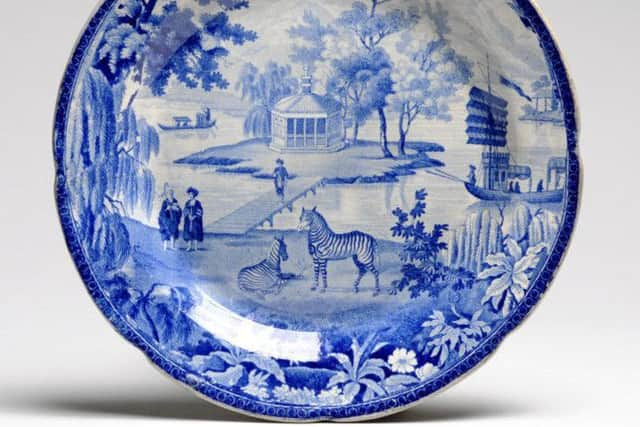

Some have Willow patterns and Chinese-influenced stylings, but, said Ms Arscott, “most are plain – no decorations, no frills and no fancies. It meant the potteries could save production costs by not paying painters”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYorkshire’s potteries were centered on Burton Lodge near Driffield, and in the Hunslet district of Leeds, close to the River Hull and the Aire respectively. The Leeds activity was at its peak at around 1835, but most pieces from the period were not marked, making it hard to attribute pieces to individual potteries.

“It wasn’t on the same scale as the Potteries in the Midlands, but it was a big industry in the area and a lot of people were employed in it,” said Ms Arscott.

By the mid-19th century, creamware had become sufficiently affordable for even lower class-families.

“Yorkshire pottery is a real economic indicator of a period when the middle classes were expanding,” Ms Arscott added.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe 22 items on show at the university’s Stanley and Audrey Burton Gallery have been drawn from the in-house art store, and include examples of twisted rope handles, braidings and flutings intended to make the crockery look more expensive than it actually was.

“It was obviously made quite cheaply and a lot of it is much lighter than you would expect,” Ms Arscott said.

The collection betrays kitchen customs of generations past – with examples of jelly moulds and knife rests that would protect the best tablecloth.

There is also a tiny floral teapot from the early 19th century, a time when tea was too expensive to be drunk in anything but the smallest quantities.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDespite the lack of decorative art in most of the pieces, one design, which used transfers rather than hand painting, managed to throw everything but the kitchen sink at the Yorkshire tea table.

The blue and white plate has not only Oriental figures and a sailing junk, but also a pair of African zebras in the background.

The exhibition, in Leeds University’s Parkinson building, is open until March.

Leeds Pottery in Hunslet was region’s biggest producer of creamware, and exported its plates across Europe.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe firm was founded by Richard Humble and John and Joshua Green around 1770 and began trading under the name Humble, Green and Co before becoming Warburton and Britton and finally Richard Britton and Sons.

Its factory in Dewsbury Road boasted a row of huge brick kilns and a converted windmill, which replaced a flint mill at Thorp Arch. After its closure in 1881 the site became a corporation gasworks.

The original potteries of the East Riding are little documented, but the industry saw a revival in the 1970s with the success of the distinctive designs of Hornsea Pottery.