The Yorkshire statues and sculptures that have inspired a new exhibition

The Lovers is its official name. To a generation of Doncaster shoppers, however, it was more explicitly known as “The Copulating Couple”.

During the 1970s, this enigmatic statue rotated gently in the town’s Arndale Shopping Centre (now the Frenchgate Centre), showing a naked couple standing hip-to-hip, arms thrown back in apparent ecstasy. It was particularly eye-catching as you came out of Boots or British Home Stores.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt became a popular meeting place. “See you at the Copulating Couple,” people would say, even if they had nothing more raunchy in mind than a nice cup of milky coffee and a toasted teacake at BHS.

Taken down in the 1980s, it spent many years languishing in a suburban garden, but was rediscovered four years ago and installed across town at the Waterdale Centre.

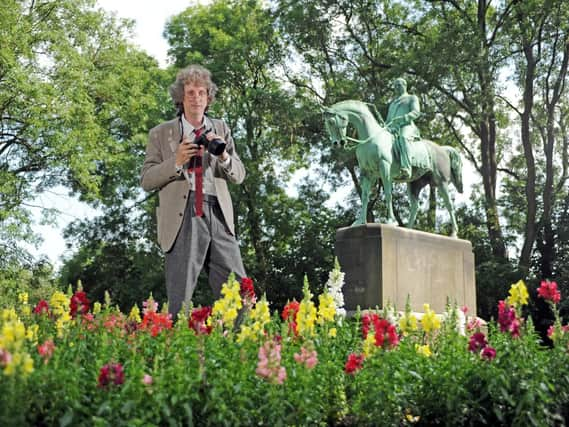

“It was a joy to find,” says Vic Allen, who includes it in his new photographic project, Monumental Oversights. This eclectic survey of four dozen Yorkshire statues and sculptures has inspired an exhibition at Dean Clough, the vast Halifax arts and business complex where Allen is Arts Director. It has also spawned a no-punches-pulled book and an online “digital exhibition”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe featured statues, mostly erected to make the great and good look even greater and better, range wide across Yorkshire and its achievements. They take in Fred Trueman, Harold Wilson, Captain Cook, Dickie Bird, Amy Johnson, Philip Larkin, Billy Bremner, Constantine the Great, William Wilberforce... and The Black Prince, whose Leeds statue was the project’s starting point (we’ll come to this).

Allen says the exhibition “explores Yorkshire through some of its public sculptures” and includes statues of once-famous people who’ve been forgotten (like Victorian MP Sir Mathew Wilson in Skipton) and people “who deserved to be famous” like Sheffield’s Women of Steel, who worked in the city’s armaments factories, and Hull’s Lost Trawlermen, the 6,000 lost at sea.

The pictures stand up in their own right, but the book’s commentary – aiming to “explore the politics of the public realm” – puts them in a predictably opinionated context. If you read Vic Allen’s My Yorkshire feature in this magazine a few weekends ago, you’ll know what to expect.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAllen, who edited Yorkshire’s Artscene magazine for 15 feisty years, is not a man to risk bland predictability if controversy is a tastier option. Wiry, puckish, with a shock of curly hair, he’s a whirlwind of words, a tumult of thoughts.

Ideas jump up and down when he’s talking and wave frantically for attention. He’s clever, subversive, outspoken, full of attitude and wry amusement, and so critical that he even characterises his own book as “arbitrary and incomplete”, full of “snide remarks that conceal an awkward fondness” for the chosen statues and sculptures.

Take Ian Judd’s commanding statue of pipe-clutching JB Priestley, coat billowing, outside Bradford’s National Science and Media Museum. In the book, Allen praises the statue (“the expression is convincing, the detail judicious and the stance credible”) before a tirade against Priestley himself. “The windy old hypocrite looks out over the town he chose to define him,” he writes.

When we meet at Dean Clough’s vibrant cafe, he elaborates on all this. “Everything he writes annoys me,” he says. “It’s the windy outdatedness of it all....”. Windy? Oddly enough, when Bill Bryson visited Bradford nearly 30 years ago to research Notes from a Small Island, he noted that Priestley’s flying-coat-tails stance “makes him look oddly as if he has a very bad case of wind”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEnough of wind. The Monumental Oversights project started as a response to the current Yorkshire Sculpture International, which Allen felt under-represented the county’s own sculpture and sculptors. “I’m against exclusivity,” he says. “I thought: Let’s bring public sculpture into this.”

So he set about “compiling dull images of the boring public statues which inhabit the county”. An odd self-recommendation, I say. It’s irony, he says with a smile. The book’s introduction begins: “I am no expert. There are, here, few original facts and probably much that is dubious.” Isn’t this counter-salesmanship, Vic? Irony, he repeats.

Priestley gives way to another riff, this time about the sober statue of the 19th century engineer Joseph Locke in Barnsley’s Locke Park. “On the face of it, it’s a sculpture of a man holding his coat,” he says. “It’s a dull statue, but the stories around it are terrific. He deserves at be as well known as Stephenson and Brunel.”

I turn to the book’s section on Locke, but I’m distracted from his engineering prowess by a comparison between Locke Park and the Yorkshire Sculpture Park “whose roads are constipated with coaches; with people clinging onto the bull-bars of their Range Rovers as they change into over-engineered Alpine footwear; with saggy blokes in yellow vests and sunglasses squawking into their walkie-talkies...”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe project had a boost when Allen was giving the sculptor Michael Sandle a lift to Leeds station. As they drove into City Square, Sandle said how much he admired the statue of the Black Prince. Allen was taken aback: “Despite knowing Leeds for over 45 years, I’d never consciously noticed it before then.”

Talking to other artists, it emerged that they’d noticed as little public sculpture as he had. “Half of us never see the sculptures around us,” he says. “And if we do, we never think to question who they are or why they’re there.” He decided to remedy the situation.

He has excluded war memorials, animal statues and shrines and is “consciously prejudiced against Queen Victoria statues, corporate statues and obvious high-art statements”. He also takes a casual swipe at “Bradford’s Delius monument, the giant mesh packhorse in Leeds Trinity Centre, and the gift-shoppy seagulls at No 1 City Square.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo how did he choose which to include? There were obvious candidates, he says.... the gleaming gold statue of “King Billy” (William of Orange) riding like a Roman emperor over an underground Hull public convenience. Harold Wilson reaching for the pipe in his suit pocket as he hot-foots it from Huddersfield station.

Captain Cook in Whitby “overseen by the mouldering jaw of a Right Whale”. And that haughty Leeds statue of the Black Prince, who had no apparent connection with the city.

There’s the Walking Man, the doggedly striding 1957 statue by miner’s son George Fullard outside Sheffield’s Millennium Galleries. Allen notes with delight that on a previous site, the Walking Man was often seen with a cigarette stuck between his lips, a beer can under his arm and a traffic cone on his head. “Now you can’t do better than that,” he says.

Beyond all those, there’s the UK’s two largest standing stones – at Rudston near Bridlington and at Boroughbridge. There are a fair few statues by Barnsley-based Graham Ibbeson and a Halifax statue of Prince Albert on his horse Nimrod.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd there’s the row of figures on the balustrade of Harrogate’s Victoria Centre “sporting expressions that you only find in Ladybird books”. Bill Bryson was even more caustic: “It looks as if two dozen citizens of various ages are about to commit mass suicide.”

So who would Allen himself erect a statue to? Maybe, he says, Herbert Read, the influential Yorkshire-born literary critic and art historian, and we range a bit wider over possible literary candidates.

He’s not keen on erecting one to Alan Bennett, however: “Why do Yorkshire folk who are having the p... taken out of them by him adore him?” Irony, I say.

Exhibition at Dean Clough, Halifax (01422 250250; www.ac-dc.org.uk) until September 1 (free admission). The website has a link to the online digital exhibition. The book (£10) is available on Amazon or from Dean Clough (no p&p charge).