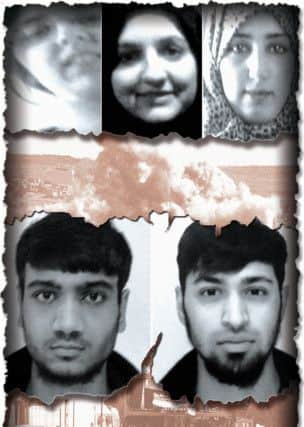

The young Muslims lured into world of terror

The Islamist “cause” is exerting as strong a pull on young British Muslims as the fight against fascism in the 1930s, a struggle which drew thousands of volunteers from this country to fight in the Spanish Civil War.

As comparisons go it may seem improbable, but it’s a view that underlines the fact there are no easy answers to the radicalisation which this week saw Dewsbury teenager Talha Asmal become Britain’s youngest suicide bomber and three Bradford women apparently join Islamic State, taking their nine children with them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere is a growing sense that recruiters from terror groups such as IS are exploiting simmering resentment sparked by the plight of Muslims across the Middle East, struggles with self-identity and young people’s natural “sense of adventure” to sell a compelling picture of jihad.

Asmal, a “quiet and hard working” 17-year-old, blew himself up in an IS attack on an oil refinery near the Iraqi town of Baiji. Meanwhile police believe sisters Sugra, Zohra and Khadiya Dawood have followed in the footsteps of their brother, who travelled to Syria to fight for Islamic State two years ago.

Then there is Thomas Evans, the 25-year-old from Buckinghamshire who converted to Islam in 2010. He was identified this week as one of 11 fighters from terror group Al-Shabaab who died in an assault on a military base in Kenya. “Don’t cry for me,” he had told his mother in his final phone call home. “I’ll be in paradise.”

But just what is driving these Britons into the arms of militants intent on spreading terror around the world?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Often it is simply a question of being young,” says Dr Afshin Shahi, director of the Centre for the Study of Political Islam at the University of Bradford. “Certain things that are happening in the Middle East are extremely appealing to 17 and 18-year-olds. They believe they are part of a revolutionary organisation and about to change lives, to make history.

“In a way it is very much like the International Brigades who joined the fight against fascism in the Spanish Civil War. There is a sense of mission and an ideological agenda, but most of all it seems very exciting to them.”

What makes the task of tackling this deadly lure an immensely complex one, he says, is the lack of a unified voice within the Islamic faith in this country and, more pertinently, the fact that there is no single route to radicalisation.

Only by putting the myriad of factors together, he argues, can we hope to have a better understanding of what leads young men and women to join the militants’ ranks.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne such component is the search for a sense of identity, a rite of passage familiar to most teenagers but which he believes takes on even greater significance for young British Muslims. While their parents may have come to this country willingly and be grateful for the opportunities it has offered them, they often feel differently.

“For them there was no choice and a lot of young Muslims don’t feel 100 per cent accepted or integrated in society. The rise of Islamophobia since 9/11 means some youngsters feel that their sense of self-worth is under attack. That makes them more vulnerable to the ideologies of an organisation such as Islamic State.”

The situation in the Middle East is now proving the lightning rod for such discontent – not just in Yorkshire or Britain, but right across Europe.

“What happened in Gaza last summer, the images of dead Palestinian children, are ammunition for jihadi groups who feed off that anger and frustration,” says Shahi. “It is very easy to channel that into what is happening in Iraq and Syria because people feel frustrated and they want to do something about it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Some may go there as part of a humanitarian cause, only to then find themselves being drawn into something else entirely.”

It is a view echoed by Qari Asim. An imam at the Makkah Masjid mosque in the Hyde Park area of Leeds, he received an MBE for his efforts to build bridges between the city’s communities in the wake of the July 7 terror attacks which were carried out by a gang of four bombers, all of whom were raised in West Yorkshire.

He points to similar elements as being the key drivers of radicalisation and likens IS leaders to paedophiles in their grooming of young men. “These people use (young people’s) passion to realise their own political views and aims. They tell them that they will enter paradise, which is completely contrary to the teachings but these young people aren’t knowledgeable enough to know that these are lies.

“You can be led down the garden path thinking you are going to change the world. That passion is noble but we need to find a way of channeling those energies in the right way.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Here we hold workshops which give young people a safe space in which to air their views, because if they are not heard then they are going to be expressed somewhere else. But we need to deal with some of the things that are used to manipulate these people. That comes down to foreign policy and a lack of economic opportunity.

“You could say that it’s the same for all young people, why should Muslims be any different? But there is a sense of isolation and a feeling of Islamophobia that can drive some to harbour resentment and commit acts of terror. People can be turned into monsters, either knowingly or unknowingly.”

And, as has been seen with Talha Asmal, there no longer appears to be a ready set of criteria for determining who is at risk of radicalisation.

“The days when you could only link its causes to deprivation, lack of education and poverty are gone,” insists Shahi. “They are still important but jihadis in Iraq and Syria are coming from middle class, comfortable backgrounds. It is why it is essential that we look at every case on its own merits.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“One of the important challenges is that the Islamic community in Britain is extremely scattered which means it’s very difficult for leaders to have a cohesive policy or discourse that could be implemented universally.

“Even if the vast majority of leaders in Yorkshire, Britain or Europe have an agreement over certain approaches to radicalisation, they don’t have a coherent structure in place to provide universal authority for Islam. And, of course, they have no control over what is available on the internet.

“It all goes back to the fact that Islam has no central or universal voice, so anyone can promote their own version of it. That presents a very big challenge when you are dealing with a problem like radicalisation.”

But if many of the region’s Muslims point to beefed-up anti-terror laws as a source of growing resentment within their community, particularly among young people who feel they are being unjustly targeted, they readily admit that the greater the numbers joining the likes of Islamic State, the louder the calls will be for a clampdown. It’s a vicious circle that’s hard to break.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“All this counter-terrorism legislation and negative media portrayal of Muslims is having a profound effect on the psyche of young Muslims,” agrees Bana Gora, chief executive of the Bradford-based Muslim Women’s Council. “The recent incidents in Gaza do bring a lot of raw emotion to the forefront, but there are other ways to deal with that, (jihad) is not the answer.”

One of the organisation’s primary concerns when it comes to radicalisation is the lack of space within mosques where women and young people can air their grievances and engage in the sort of discussions which they are clear need to take place.

“What we need is a place of worship that is all-inclusive so that conversations on these issues can take place between people of all faiths,” says Gora. “If those conversations simply end up going underground then it won’t help matters at all.”