Bygones: Life-changing decision to join the cheating ‘game’ costs Johnson everything in Seoul

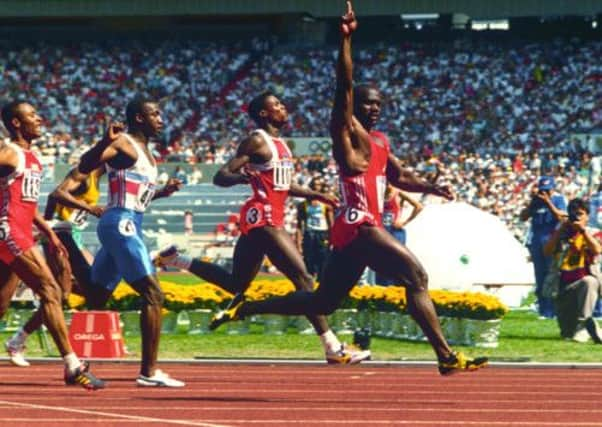

Ben Johnson, Canada’s dominant sprinter, got the better of his fierce rival Carl Lewis once again, romping to 100 metres gold at the 1988 Olympics.

On that sunny day in Seoul, he lowered his own world record to 9.79 seconds and might have gone even faster had he not raised his hand towards the end of the race.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohnson had done it, he had reached the goal he had always strived for: Olympic gold.

Three days later it was gone. The world came crashing down as a routine drugs test came back positive for the steroid Stanozolol.

“I didn’t really worry about getting caught,” Johnson said, speaking two-and-a-half decades on in the basement of a central London hotel. “I was in fear of my life so if I do get caught I said at the time ‘I’ll deal with it when the problem came’.

“The problem came, so I dealt with it. I took the bull by the horn, this is what I did, this is what happened, move forward. That’s it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“No panic, no fear. Even with what happened I still have tremendous fans until this day.

“Everybody wants to embrace me and be with me and take pictures – it’s just getting greater and greater as time goes by.”

A long time may have passed, but it is surprising to hear Johnson speak so matter-of-factly about the incident that made him the most infamous drugs cheat of the 20th century.

He still claims “sabotage” in Seoul, insisting he was spiked with Stanozolol, but does not deny being a drug cheat.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen Johnson watched sport as a kid, he thought everybody was clean – an illusion shattered by his coach in the early 1980s.

Told his rivals were doping, after weeks of deliberation the temptation of glory proved too much for him.

“As a young boy, my God, what a decision to make,” the Jamaican-born sprinter said.

“I was running clean but thinking ‘how am I going to win against these guys doing what they’re doing?’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I decided that wasn’t fair, I’m going to join the game. And that’s what I did. I didn’t tell my mother about it, or anybody else, just kept it a secret.

“I came back to the track and I say, ‘yeah, I will try it’. And ever since things change, my life.”

Johnson will never be forgiven by many for what happened, but is, belatedly, trying to make a difference as the unlikely face of a new anti-doping campaign.

The sprinter recently kicked off a world tour with sportswear company SKINS as part of the initiative culminating at the scene of the crime: the Seoul Olympic Stadium on September 24, the 25th anniversary of the 100m final.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Winning a gold medal and being the best in the world ... it cost me my reputation, my life,” Johnson said. “I’m here to try and change that.

“I’m trying to clear the air and clear my part of life, trying to help future generations and future athletes, athletes of my calibre, who have tested positive, been in the same boat as me, trying to help them and say you’re not alone.

“If I can help change the mind of athletes in generations to come, that’s what we are here for.”

Johnson is not receiving any payment to lead the #ChooseTheRightTrack campaign, which aims to radically improve a system that athletes are still breaching today.

“Most athletes want to win,” he said. “It’s a temptation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Once you go across that bridge there’s no turning back. You want to win? You want to win a gold medal? Be the fastest in world? You keep asking yourself these questions.

“This is the price you have to pay, but this is what you can get in the end, on the other side. What choice are you going to make?

“Yes, I do have some regrets. What I did was wrong. But now I’m trying to change that.”

In the years following the 1988 race, a number of the other finalists were also implicated in drug scandals.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHere we look at the other runners that day who have a cloud over their name.

Lane 2: Ray Stewart, Jamaica (8th, 12.12secs) – A leg injury saw him finish last of the finalists. In 2008, by this point a coach, Stewart was implicated in a drugs scandal. He continues to protest his innocence.

Lane 3: Carl Lewis, United States (2nd, 9.92s) – Eventually awarded the 100m gold following Johnson’s disqualification. In 2003, news broke that he had failed three drugs tests at the 1988 Olympic trials. He maintains his innocence.

Lane 4: Linford Christie, Great Britain (3rd, 9.97s) – Bumped up to silver following the disqualification, he went on to win gold four years later in Barcelona. Avoided punishment for positive test for a banned stimulant after 200m in Seoul, but banned for two years in 1999 after Nandrolone found in system. Denies wrongdoing.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLane 6: Ben Johnson, Canada (1st, 9.79s) – Lowered his own world record time to take Olympic gold in Seoul. Three days later tested positive for Stanozolol and stripped of title. Maintains it was a case of sabotage, but accepts wide-ranging doping, testing positive on two further occasions.

Lane 7: Desai Williams, Canada (7th, 10.11s) – At the Dubin Inquiry, established by the Canadian government following Johnson’s disqualification, a Toronto doctor testified that he had supplied the sprinter with anabolic steroids for which he escaped punishment.

Lane 8: Dennis Mitchell, United States (5th, 10.04s) – Winner of the 100m bronze and 4x100m gold in 1992, tested positive for excessive testosterone in 1998 and banned for two years by IAAF. Testified at trial of his former coach that he had been injected by human growth hormone.