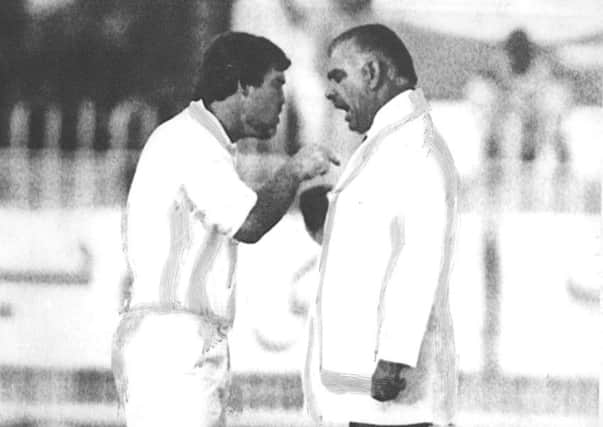

Bygones: Mike Gatting and Shakoor Rana square off in an unsavoury moment for sport

“Dear Shakoor Rana, I apologise for the bad language used during the 2nd day of the Test match at Fisalabad (sic). Mike Gatting, 11th Dec 1987.”

To say that the apology lacked the essential quality of sincerity is an understatement.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBranded a “******* cheating ****” by Rana towards the end of day two of the second Test between England and Pakistan at Faisalabad, after the umpire had claimed that Gatting moved a fielder behind the batsman’s back as Eddie Hemmings ran into bowl, the England captain responded with a few choice words of his own.

Images of the pair squaring up at the Iqbal Stadium, with Gatting shouting and jabbing his finger towards an equally militant Rana, were beamed across the world and constituted one of the lowest and most controversial moments in the game’s history.

Eventually, Gatting – who had actually told the batsmen that he was bringing up David Capel from deep square-leg, and was merely signalling to Capel to stop as Hemmings ran in – was pulled away from the umpire, and there were hopes that the situation would be diffused overnight.

But those were emphatically dashed when Rana refused to take to the field on day three and demanded a written apology from Gatting, who agreed on condition that Rana, in turn, apologised to him – something that Rana was unwilling to accept.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd so the world witnessed the remarkable sight of Gatting leading his men on to the field for day three in front of around 2,000 spectators and a large number of armour-clad riot police only for neither Rana, his fellow umpire nor the batsmen to join them.

Like people standing around at a bus stop in the hope that one might soon appear, England lingered for a time before eventually sloping off back to the pavilion, where they remained for the rest of the day.

Peter Lush, the England manager, emerged to inform reporters that there was a deadlock between Gatting and Rana, with the umpire – apparently egged on by Pakistan captain Javed Miandad – refusing to budge.

As discussions went back and forth between Faisalabad and Lord’s, the Foreign Office got involved amid fears that the tour could be cancelled, leading to potentially damaging financial and legal consequences.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe upshot of the discussions was that England’s players were basically told to get on with it and Gatting ordered to apologise under duress.

Shortly before 10am the next morning, the fourth day of the match, he backed down and Rana had his “victory”, the England players reacting by producing an angry, contract-breaching statement in protest at the way that Gatting had been treated.

Gatting, whose side had been enraged by woeful umpiring earlier in the match and also during the first Test in Lahore, told journalists that he was considering his position as player and captain.

When he was sacked from the captaincy six months later, ostensibly for a dalliance with a barmaid, many felt that it all harked back to what happened in Faisalabad with Shakoor Rana.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRelations between England and Pakistan – never as smooth as a baby’s backside – had been on something of a knife-edge since 1982. Pakistan blamed their series defeat that summer on one of umpire David Constant’s decisions during the Headingley Test and asked that he not be allowed to officiate when they toured again in 1987.

But the Test and County Cricket Board dug in their heels and Constant stood in the opening two games.

As Gatting later lamented: “The bad feeling engendered may well have lit a very long fuse that went all the way to Faisalabad.”

It was further felt that Pakistan’s poor performance during the 1987 World Cup – which directly followed their tour of England and came just before the winter Test series re-match – had a knock-on effect on the Faisalabad furore.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPakistan cricket needed a lift as a result of those World Cup displays and there was talk of pressure being put on the home umpires by the Pakistan authorities to ensure that the Test series went well for the hosts.

There seemed clear evidence for this in the first Test in Lahore, where Pakistan won by an innings after Gatting himself got an appalling lbw decision. In the second innings, Chris Broad refused to walk when given out to a ball he did not hit, Graham Gooch eventually persuading his partner to return to the pavilion.

At Faisalabad, where England had been further riled by umpire Rana wearing a Pakistan sweater beneath his jacket, the tourists were on top when Gatting’s finger-jabbing row with the official blew up. Pakistan were 106-5 in reply to England’s first innings 292, but the lost third day was never replaced and England had to settle for a draw.

The third and final Test in Karachi was also drawn after the Pakistan authorities had further fanned the flames by naming Rana as one of the two umpires for the match along with the similarly unsatisfactory Shakeel Khan. Eventually, commonsense prevailed and two different officials were appointed – if only after yet more tense negotiations.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe tour ended bizarrely when the Test and County Cricket Board – mindful of the difficulties that Gatting’s men had faced – awarded each of the England players a £1,000 “hardship bonus”, a move that did little to heal the fractured relations between the two countries. It was also reported that Gatting received a letter from Rana expressing regret at what happened in Faisalabad but in which the word “apologised” was scrubbed out.

Publicly, however, Rana was unrepentant. Speaking after the brouhaha, he said: “In Pakistan, many men have been killed for the sort of insults he (Gatting) threw at me. He’s lucky I didn’t beat him.”

Rana added, perhaps tellingly: “I do not regret what happened. How can I regret? It made me the most famous umpire.”

Rana, who allegedly kept Gatting’s handwritten apology under his pillow, umpired three more Tests before retiring in 1996.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlways happy to relive the events of Faisalabad (in direct contrast to Gatting, who admitted that “it wasn’t a very proud moment of my career”, even if it “might have helped instigate the neutral umpires that people were pushing for at the time”), Rana liked to tell of the time when he met Gatting outside Lord’s some years later.

According to Rana, who died in 2001, aged 65, the exchange went like this… “I went to shake his hand. He said, ‘Oh God, not you again’ and drove away.”

Qadir’s work leaves England in a wrist-spin

THE star of the 1987-88 Test series between England and Pakistan was Abdul Qadir.

The Pakistan leg-spinner took 30 wickets in the three games, including 9-56 from 37 overs in the first innings of the opening Test in Lahore.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith his distinctive, bounding, angled approach to the crease, Qadir bamboozled the England players with more than a little help from the home officials.

However, his impact might have been no less significant without their assistance, the consensus being that he delivered a masterclass in the wrist-spinner’s art.

“It is impossible to believe that wrist-spin has ever been bowled better than Qadir did in his home city of Lahore in

1987-88, when he took 9-56,” wrote Scyld Berry.

“Graham Gooch, who faced him that day, said Qadir was even finer than Shane Warne, to whom he passed on the candle.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdQadir took 13-101 in the game in Lahore, followed by 7-150 in Faisalabad and 10-186 in the last Test in Karachi.

During this era, he near single-handedly invigorated the wrist-spinner’s art later popularised by Warne.

Now 62, Qadir played 67 Tests between 1977 and 1990, taking 236 wickets at 32.8.

He also played 104 one-day internationals, capturing 132 wickets at 26.1.