Weekend Interview: Jamie Lawrence - How football saved me from a life sentence

Not just in the years before he made it as a Premier League footballer, when he was twice sent to prison.

But more recently, too. Hanging up his boots sparked a downward spiral that almost brought a return to the life Lawrence had worked so hard to leave behind when embarking on a playing career that brought almost 400 appearances.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Football was similar to my prison sentences in that my life had a structure,” the 48-year-old tells The Yorkshire Post. “You know what every day is going to involve, what you will be doing at a certain time.

“Once I had finished playing, I lost that structure and found things very difficult. I was also very angry after finishing, probably with football, and trying to hide that by drinking a lot.

“Then the money started to dry up and I nearly went back to crime. I was very, very close. What stopped me doing something stupid was one of my closest friends. He is doing a big sentence, something like 30 years.

“He sat me down and told me, ‘Sort your life out – you don’t want to be sitting next to me in a cell’. The penny suddenly dropped.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

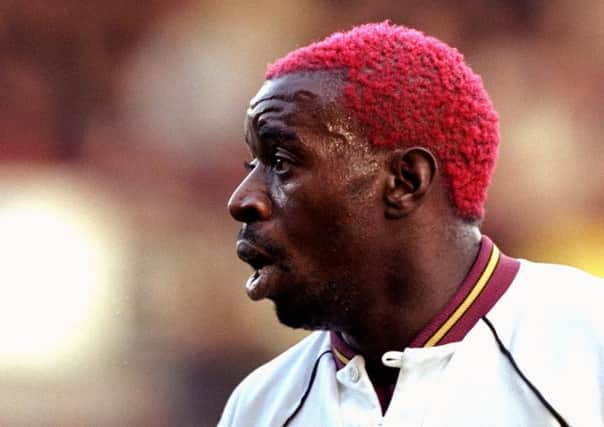

Hide AdLawrence, the morning we meet in London, looks as fit as he did when hurtling down the right wing at breakneck speed sporting the colours of Bradford City.

His new job as a mentor to inmates at Brixton Prison is going well and it shows. He knows the value of someone, anyone, believing in a prisoner who genuinely wants to turn his life around because Lawrence was that man in the early Nineties.

Jailed for three years as a 17-year-old after being found guilty of robbery, Lawrence had been out for only three months when he fell foul of the law again.

A four-year sentence followed for violent robbery and Lawrence’s life seemed mapped out. Then, though, came a move to the tough Camp Hill prison on the Isle of Wight and a gradual realisation that football may yet provide a way out.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith the encouragement of Eddie Walder, a physical training instructor at the prison, Lawrence joined local semi-professional team Cowes Sports and then, once released, impressed sufficiently on trial at Sunderland to earn a one-year contract.

“Going to Sunderland was my saviour,” he says. “It was 300 miles away from London and, suddenly, I was free to make my own decisions.

“It is the big message I try to get across when I go into the prison and hold the workshops. Don’t go back to the same area, give yourself distance from that old crowd.

“Not that you cut people off. You can still be their friend, even if they are on the wrong side of the law. My mates all still came to watch me play.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“But I had to put a bit of distance between myself and them. If they are your friends, they will understand you are trying to turn your life around.

“I believe everyone has something they are good at. A talent. You just have to find it. Football was my talent and I knew I had to stay out of trouble if I was going to be able to make the most of that talent.”

Lawrence made his debut for Sunderland as a substitute at Middlesbrough just two days after signing. ‘Jailhouse Rock’ was mischievously played over the PA system as he warmed up, making him chuckle.

The next dozen years were spent with a variety of clubs, including stints in the top flight with Bradford and Leicester City. He also played more than 40 times for Jamaica.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is this CV that makes him the ideal person to strike a chord with the prisoners of today determined to forge a new life.

“A lot of these lads don’t have role models in their life,” adds Lawrence, whose own descent into crime came after deciding to stay behind in London after his parents had left for Jamaica when he was a teenager.

“These boys have not had that father figure in their lives. So, the gangs have been the big thing in their life. Then, the next minute this gang has you pushing drugs or whatever.

“People have let them down all their life. So what you have to be is a constant in their life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“They will try and push you away at first. They don’t want to be hurt again. But if you prove you will be there all the time then they open up. They let you in.

“I have lived the same life as them. I have been inside at Christmas, which is just the worst time. Everyone is celebrating on the outside and you are stuck in a cell. And no-one comes to see you because they are too busy enjoying themselves.

“I can still remember my prison numbers. The first was PN2991Lawrence and then my second stint, KR2879Lawrence.

“Maybe because I have been in the same place is why they been great with me but reluctant with others.

“I also understand what they are facing.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Once they have a criminal record, they are tarred with that for life. It can make it difficult to get a job, earn money. It follows them around. So you can see why many reoffend after being released.

“My role is to try and show them an alternative. And offer them support. Same when these lads come out, too.

“There has to be that side. It is easy being there for them inside but the support they really need will be once on the outside.”

At the moment, Lawrence’s visits are restricted to just Brixton. But plans are afoot to extend the scheme into other prisons, including Feltham and Cardiff.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I love the job,” said the 48-year-old, who also works as a physical trainer with a host of sportsmen, including England midfielder Ruben Loftus-Cheek.

“Going through the front door at Brixton felt like full circle but what I really love is seeing the difference it can make to people’s lives.

“That is worth more than anything you can buy. My mum died this year at 88 and she was my queen. Mum helped people all her life and I think she would be very proud of me.

“I always think back to what Eddie (Walder) did for me on the Isle of Wight. He is my hero. Without his help and support, after being released I would have gone straight back to what I had been doing. I am 100 per cent certain of that.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I would be in the cemetery now or serving life in prison. That is how bad things had got. I will never forget what Eddie did for me.

“If someone says in 27 years time that Jamie Lawrence turned him away from that sort of life, the feeling would be better than anything I did on a football pitch. No goal or victory or even promotion would compare with saving someone’s life.”

The Jamie Lawrence story ...

Jamie Lawrence loved being a footballer, winning the League Cup with Leicester City and helping Bradford City, a club where he is still revered today, into the Premier League.

But the Londoner admits the one letdown in an otherwise enjoyable career was his final couple of seasons in the Football League.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I left Bradford (in 2002) for Walsall and played for the worst manager ever,” he says. “Colin Lee had been my coach at Leicester but he was a nightmare.

“I signed with a minute to spare. I should have waited another minute! Lee messed me about. He gave me two extra weeks off one summer after I had been playing for Jamaica in the Gold Cup but then called me back after two days because they had lost a friendly.

“We had a ‘Tuesday Club’, lads like Paul Merson, Vinny Samways and Darren Wrack going out together. I got the blame for leading them astray!

“He sent me to Wigan, which was great as I could play for ‘Jagger’ (Paul Jewell) again. I was flying and Wigan were going for promotion.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“But the horrible man at Walsall said, ‘No, we need you for a relegation battle’. So, I had to go back. I didn’t play at all and six weeks later Walsall paid me up. But the move to Wigan had gone by then. I then had a final year at Brentford under Martin Allen, who was not my sort of manager.”