Irate fans, online rows and battles with BBC bosses: What it is like to edit Match of the Day

Most football fans are not naturally sympathetic towards referees. But after 15 years of editing Match of the Day – and frequently incurring the wrath of supporters convinced of unfair bias against their beloved side – Paul Armstrong can certainly see things from their perspective.

The genial Middlesbrough fan likens the pressure of delivering a successful live 90-minute broadcast each week to an audience of millions to being one of the officials who are more often derided than praised.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It is a bit like being a referee, if nobody has noticed your performance that is a good thing,” he explains. “The running order is subjective but if you have a reasonable explanation for it and you leave thinking you haven’t dropped a clanger or missed anything, then you are ok.”

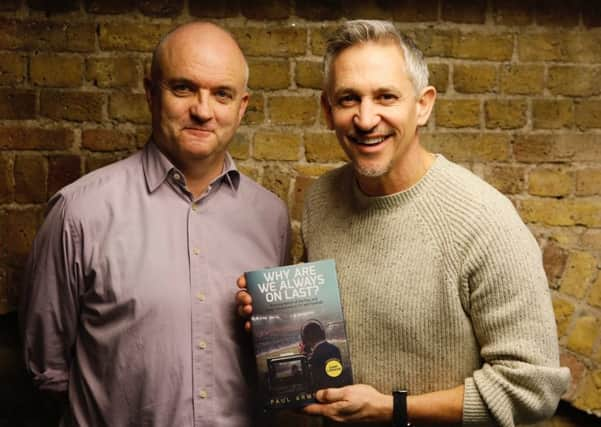

Armstrong, whose extraordinary career has also involved travelling the world to work at seven World Cups and five Olympic Games alongside some of the greats of sports broadcasting, has just published his first book, Why Are We Always on Last? Running Match of the Day and Other Adventures in TV and Football after taking redundancy from the BBC in 2016 due to worsening ear problems.

His job entailed deciding how long the highlights and analysis of each game were shown for – and most contentiously, the order they were shown in.

The book title is a light-hearted reference to the frequent complaint of fans of smaller clubs who perceived their sides were being discriminated against when it came to choosing which order to show matches in – a problem that reached its zenith when Armstrong set up a short-lived Twitter account called @motdeditor, which swiftly amassed 300,000 followers in 2011.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Once people got the idea you could talk straight to the editor and let them know their feelings, it took off,” he says.

“I was probably not the best person to deal with that because I did occasionally lose my temper!”

He explains in the book he ended up being “ticked off by the uber-bosses” after one too many “squabbles with the more abusive and pig-headed” viewers.

“For some reason, how long each club featured in the opening titles that season (not much more than one second in some cases, pushing two in others) was the hot topic creating fury, and by late September I’d decided that life was too short,” Armstrong says. “I can’t find anything other than benign references via Google now, but it must have got a little out of hand because I was ticked off by the uber-bosses. I may have suggested that a furious Stoke tweeter was a one-eyed numpty for not spotting Peter Crouch’s left ear in the opening titles, or possibly worse.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was not the first time online remarks had got him into hot water. In December 2006, he wrote a BBC blog attempting to dispel a persistent rumour that MoTD commentators did not actually attend games – something he now describes as “an early example of fake news”.

When he responded to comments on his post from people insisting he was not telling the truth, the trouble really began.

“Appropriately for pantomime season, this just degenerated into ‘Oh no they’re not, oh yes they are’, and after several days of ping-pong with the kind of people who probably think the moon landings were staged I ended the conversation with a not particularly festive, or Reithian, ‘Make like a turkey and get stuffed’,” he explains in the book. “It’s quite funny in retrospect but I was hauled over the coals for insulting the licence payer.”

But despite his occasional run-ins, Armstrong says he generally enjoyed the feedback he got from viewers as it showed how much people cared about the show.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut social media is not the only development broadcasters have had to adapt to in recent years. Armstrong says the biggest change since he started at the BBC in the 1980s is the sheer number of competing sports channels – something he says is not necessarily negative.

“It is definitely a good thing you don’t have a Grandstand-type situation any more where every major sport is trying to find airtime on one channel. I remember trying to watch England in the 1979 Cricket World Cup final and they kept going to different sports so you hardly saw any of it. I don’t think anybody would go back to that and you can’t ever turn the clock back.

“The problem now comes with people having to subscribe to Sky and BT to see what they want and the next football deal will involve certain games on Amazon. But that is where Match of the Day comes in with the chance to watch a digest of it all. When Sky first came in, I don’t think anybody thought Match of the Day would survive but it has gone from strength to strength.”

Armstrong, who grew up in Stockton-on-Tees, landed a place on a BBC production trainee scheme in 1987 after “letting rip” about a “boring and predictable” Match of the Day broadcast featuring a then-dominant Liverpool side as part of an application task to review a programme. Thinking of becoming a newspaper journalist at the time after graduating from Oxford, he says he was shocked to be offered a place on the BBC scheme and believes he was chosen as something of a ‘wild card’ as the “token blokey sports one who was northern as well”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter initially working with the ‘unfailingly kind’ Mike Neville on Look North, one of Armstrong’s next role was more of a baptism of fire as he joined the production team for Question of Sport, where he wrote questions for David Coleman who he says would be nonplussed if any facts were incorrect.

“It was intimidating but it was a really good apprenticeship for knocking a bit of sense into me. David Coleman was past his most ferocious by the time I worked with him after he dragged sports coverage into the modern era,” he says. “The previous era had been a gentlemen amateurs, members’ pavilion type-atmosphere. He wasn’t like that, he was a very hard-nosed journalist. Even on Question of Sport, he wasn’t going to allow too many mistakes.

“He was hard but fair, probably like a very good football manager. You are not going to mess with him.”

His breakthrough moment in BBC Sport came at the end of the 1990 World Cup, where he made a montage of England star Paul Gascoigne set to Mark Knopfler’s Local Hero that ended up being praised by Oscar-winning Chariots of Fire producer David Puttnam among many others.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It just caught the moment. It wouldn’t look that special now as the things people can do are light years ahead of it. But it was the luck of being in the right place at the right time.”

Puttnam praised the montage when he appeared on the Wogan chatshow, then one of the country’s most-watched programmes.

“It was just an amazing accolade. I was watching at home and had my tea on my lap and thought ‘wow’. I just couldn’t believe it.”

In a career working with many of the biggest names in sport, he says his most cherished working memories involve his encounters with former Boro players.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe particularly fondly remembers a trip to Italy with Alan Hansen to interview Graeme Souness.

“When I was younger, Souness was just peerless for Middlesbrough and I was heartbroken when we sold him. Years later, I was sitting with him and Alan Hansen and I just had to pinch myself.

“You definitely have to play it cool because of the job. When I got a bit older and in charge of programmes, you have to be more assertive but in those times you just sit and listen. These guys know much more about football than I do and it is a huge honour to be in their company.”

He says one the greatest highlights of his career was being in Munich in 2001 as the match editor when England famously beat Germany 5-1 – a production that was nominated for a BAFTA.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdArmstrong was editing from a truck outside the ground but says he couldn’t resist the urge to put his head outside to savour the noise of the England fans as the goals flew in.

He says he took the later award nomination with a pinch of salt. “There is so much luck in it. If we had done everything the same and England had lost 1-0, the game wouldn’t have been remembered.”

Armstrong says the pressure of broadcasting to millions, particularly during England matches, was something he learnt to cope with. “You are always thinking you are broadcasting to one living room. I’m thinking ‘my dad is watching this and this should make sense to people I know’. But you are always conscious about it. There is nothing else on television, apart from maybe a Royal wedding, where you feel everybody is watching.”

Armstrong says he placed himself in the role of ‘chief worrier’ on Match of the Day – and reflects that the broadcasting approach of ex-players was often similar to the way they had played the game.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“As a former defender, Alan Hansen had the mentality of ‘what might go wrong?’ He was always nervous. But Alan Shearer and Gary Lineker had the confidence of ‘I’m going to score today’.

“Maybe it is because I am a Middlesbrough fan but my mindset was always, if it doesn’t go wrong, it is a bonus. I always needed a contingency plan if a game overran.

“You enjoy it afterwards, you rarely sit there thinking ‘this is brilliant’. You have always got the fear of being on live.”

While the highlights of his MoTD career included the famous final day of the 2011/12 season when Manchester City famously scored two goals in injury time to beat QPR and snatch the title from their great rivals Manchester United, one programme he looks back on with particular satisfaction was the end of the 2004/05 season, when four teams could have escaped relegation and their places in the table changed throughout the afternoon before West Brom were saved. He says the complex coverage involving ensuring the commentators knew what was going on in all the relevant other games and referencing in their descriptions of their own matches.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It was incredibly worrying about how we were going to tell the story. It ended up being a super piece of television but it was nervy because it was so complicated.”

Armstrong now spends most Saturdays watching his beloved Middlesbrough. But he says he still misses the camaraderie of watching the Saturday afternoon Premier League games live alongside football legends like Shearer and Lineker. “It is just like being with a big group of mates watching six games – it just so happens they have all played at a very high level. Between 3pm and 5pm, the job is an absolute joy.”

How Doctor Who almost took FA Cup final off-air

Gary Lineker had to intervene with the BBC One controller when corporation management threatened to take the 2006 FA Cup final off air in favour of a Doctor Who episode after the game went to penalties.

Armstrong’s book reveals the behind-the-scenes battle with BBC managers took place as a thrilling 3-3 game between Liverpool and West Ham went over time.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was told they would not be able to show the trophy presentation, only for Lineker to text BBC One boss Peter Fincham – leading to a second phone call from middle management. “We were told in honeyed tones to make sure we didn’t come off air until we’d interviewed the main protagonists, followed by a polite inquiry as to how long our closing montage was going to be.”

Why Are We Always on Last? by Paul Armstrong is out now and published by Pitch Publishing.