You’ll never make a goalkeeper... What a Yorkshire club told ‘Banks of England’

Gordon Banks, said the coach at Rawmarsh Welfare, would never make a goalkeeper.

The statistics were against him. In his two appearances in the Yorkshire League, he had let in 15 goals – and that after being dropped by Sheffield schoolboys a couple of years earlier.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut when Banks died yesterday at 81, football stopped in its tracks to salute one of the greatest players of them all, a man whose hands were said to be “as safe as the Banks of England”.

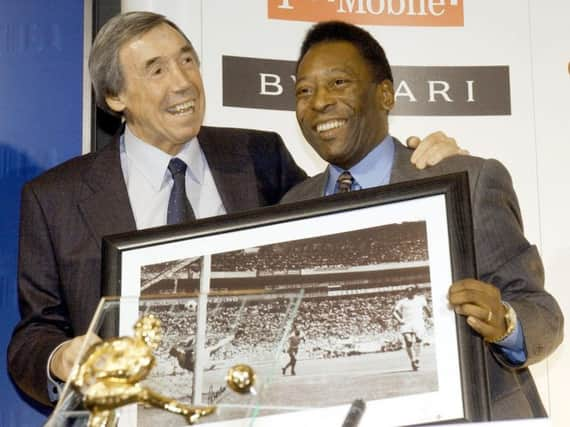

In particular, his spectacular feat in the 1970 World Cup finals, in which he appeared to defy the laws of physics by flinging himself to the right and flicking Pelé’s powerful downward header over the bar, was hailed by many as the “save of the century”.

It was the defining moment in his career. Yet it is for his part in the previous, triumphant campaign that he is chiefly celebrated – and the image of Banks and England’s captain, Sir Bobby Moore, holding aloft the Jules Rimet trophy at Wembley in 1966 is among the most indelible in British sporting history.

Banks, who revealed in 2016 that he was battling kidney cancer for the second time, had made 510 league appearances for Chesterfield, Leicester – with whom he won the League Cup in 1964 – and Stoke before retiring from the professional game at the age of 34. That followed a road accident which cost him the sight in his right eye, although he later returned briefly to the sport in America.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSir Bobby Charlton, his team-mate in the 1966 World Cup triumph, said: “Gordon was a fantastic goalkeeper and I was proud to call him a team-mate.”

He was, added, the current England manager, Gareth Southgate, “an all-time great”.

Born in Tinsley, Sheffield, in 1937, he was the son of a steelworker and part-time illicit bookmaker, and the youngest of four brothers.

The eldest, John, was disabled and never recovered from the injuries he sustained in a mugging as he carried home the takings from their dad’s shop in Catcliffe.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I grieved for months, mourned for years, and still miss him to this day, Banks wrote in his autobiography.

As a 14-year-old he played twice for Sheffield Schoolboys but was let go without reason, and the following year went to work as a coal bagger and then a hod carrier.

His return to football happened almost by accident. He turned up to watch the local side, Millspaugh, and was asked to go in goal – still in his work trousers – when the regular keeper failed to turn up.

His appearance led to an offer from Rawmarsh, but the experience was chastening, and after being told not to turn up again, he returned to Millspaugh, and served his time until the offer of a trial with Chesterfield’s youth team.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEven then, it was not plain sailing. Banks conceded 122 goals in the 1954-55 season with Chesterfield reserves, but was part of the side that reached the 1956 FA Youth Cup final.

He made his first team debut in 1958, and a move to the first division quickly followed, with a signing by Leicester.

In the six years that followed, he helped them reach four cup finals, and made his England debut against Scotland in 1963.

When his football days were over, Banks became involved in the corporate hospitality business, and became a member of the three-man football pools panel.

In 2002, Stoke City named him club president, and a statue of him holding aloft the Jules Rimet trophy was unveiled outside the stand in 2008.