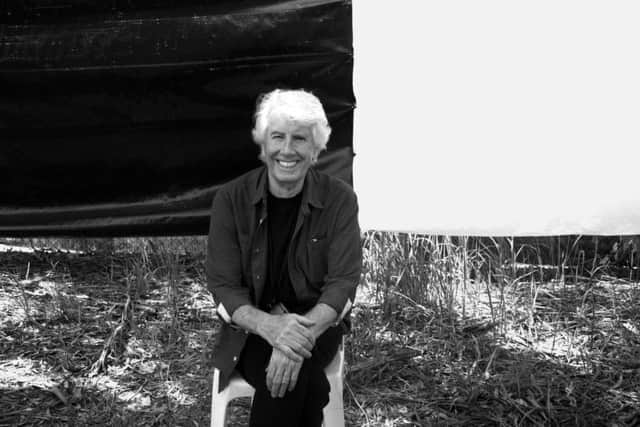

Graham Nash: ‘A lot of my songs come from ordinary moments’

As anyone who has read his autobiography Wild Tales will know, Graham Nash has a rich seam of memories.

From being screamed at by adoring fans as a member of one of the most successful UK bands of the 1960s, The Hollies, to forging a new life in California, first as a solo singer-songwriter then as part of the multi-million selling supergroups Crosby, Stills & Nash and later Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, he has lived through some of popular music’s most exciting times.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis summer tour of Britain brings the 77-year-old back to familiar turf, starting in Southport before crossing the Pennines to Halifax. He was born in Blackpool, where his mother was temporarily evacuated during the Second World War, but grew up in Salford. “I went to Southport a lot,” he recalls, “and one of my fondest memories of it, strangely enough, is rummaging around in the pebbles and the rocks underneath the pier and finding a sixpenny piece, it was phenomenal for an eight-year-old. God, that was fantastic.”

His concerts, billed as ‘an intimate evening of songs and stories’, provide an opportunity for Nash to share insights into the creation of some of his best-known work.

“I find that people that don’t write music but appreciate music are sometimes fascinated with the original idea for a song,” he reasons. “’What was on your mind when you wrote Simple Man or what were you thinking you wrote Immigration Man?’ People are interested. Very often I tell them what I was thinking.

“A lot of my songs just come from ordinary moments, like Our House. Taking Joni [Mitchell, his then partner] to breakfast in a shivering late winter Los Angeles morning, rain and cold and foggy and miserable. We passed an antiques store and she saw a vase that she wanted to buy. So we get into her car and go back to her house in Laurel Canyon, where we were living, and go through the front door and I say, ‘Hey, Joni, ‘Why don’t I light the fire while you put those flowers in the vase.’ Ordinary moments.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThough we now live in an age of individualism, Nash still believes that music really can change the world. “I have absolutely no doubt,” he says. “I think music is an incredible form of communication and I think when it’s well done it can change the world. If you change one person’s mind, have you changed the world? You have in a small way. I still think to this day that music is a very powerful form of communication and it’s very necessary in this chaotic world that we have today.”

He recognises that community values were instilled in him from an early age. “Don’t forget that our country was almost bombed out of existence twice within 20 years, by the same enemy,” he says. “When you’ve made it through the First World War and the Second World War give me a real problem to deal with, don’t complain because your coffee is cold, give me a real problem. I think that mental attitude has stood me in good stead all my life.”

Ecological themes have regularly cropped up in Nash’s songs over the years. He sees considerable cause for optimism in the climate change protests inspired by the Swedish schoolgirl Greta Thunberg. “I see great hope in what Greta is doing. These children, and their children, and their children, are going to be faced with madness.

“Climate change coming is the most important issue facing humanity, we are changing the very planet on which we live. Because of our release of CO2 and methane into the atmosphere, we are creating a world that will not support us in a way that it has in the past.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“With the melting of the glaciers and the freshening of the oceans because of the melting of the glaciers, we are going to face madness. We are going to lose most of Bangladesh, we are going to lose a lot of Miami, we are going to lose some of New York.

“This is insane and to have a leader of this country [Donald Trump] denying that it’s a fact when almost 99 per cent of the scientists throughout the world say the opposite, we are in deep trouble here, and I think we may have even passed the tipping point to be able to really do anything because it’s incredibly hard to move this planet’s momentum, it takes years.

“We thought we might be able to help stop the Vietnam War in a year and it took years. The momentum of the planet is such that it can only go a tiny bit, even with the most energy, and we are facing a dire future, I’m afraid.”

Things seemed very different in the 60s. Nash remembers the hysteria that The Hollies, the Manchester pop band that he co-founded with school friend Allan Clarke. “First of all we laughed at it,” he says. “We were just five kids from the north of England that had made a couple of records that people really liked and then our lives were changed drastically.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The Hollies were a pretty good band. We knew what we were doing, we knew what we were there for – to entertain people, to make them shake their ass and have a good time dancing. But then, who would have known? I’m 77 years old and I’m talking about the last 60 years of music. This is insane, but it was very enjoyable.”

Over The Years, Nash’s last compilation album, featured a demo version of the song Marrakesh Express that The Hollies rejected, triggering his departure from the group.

“I had written that song for The Hollies in 1966 after I had been on a holiday to Marrakesh,” he remembers. “To me, that song needed the energy of a train going through the track. There is a version that The Hollies recorded that is now in the bowels of Abbey Road in London and when you listen to it there’s no energy, it’s completely flat. Now when you look at the CSN version, Stephen [Stills] brilliantly realised that it needed the energy of a train and that’s what he put on there with his two overdubbed electric guitars. David and Stephen loved the song.

“Come on, I’m a musician, I had heard me and David and Stephen sing, I know that they loved the songs that I had, I certainly loved the songs they had, and I realised after we sung together and made our two brushes into one that I would have to go back to England and leave The Hollies. People thought I was crazy, but I had heard me and David and Stephen sing and I wanted that sound.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDespite the pedigree of all three members of CSN – Crosby had been a member of The Byrds while Stills had been in Buffalo Springfield – CSN were turned down by The Beatles’ label, Apple. “We were mystified,” says Nash.

“I found out much later that the reason why George [Harrison] didn’t want to sign us was that he thought we were brilliant and he thought the music and the harmonies were completely unique but he knew that Apple Records was going out of business and he did not want us to sign to a record company that might not be there in four months.

“I only find that out recently because that was what [former Apple A&R man] Peter Asher said in a stage show that he did.”

Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young might have gone on to enjoy considerable success but they have also had their share of disagreements. Nash says he doesn’t think tensions might have aided their creativity. “I think music was the driving force,” he says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“When Stephen sits you down and plays you Suite Judy Blue Eyes or Neil sits you down and plays Ohio or David sits you down and plays Long Time Gone I mean, come on, I’m a musician, I want those songs, they’re great songs. Let me do my stuff and let me sing and make them better, that’s what I’d like to do, and we’ve done that. I try and concentrate on the joy.

“There have been a couple of CSNY books published here in America and I’ve read David Brown’s – he was a writer for Rolling Stone – and unfortunately it just talked about how we f***ed up. I know how we f***ed up, I was there, I know all that, but where is the joy in what we had discovered musically? Where is the joy in Teach Your Children going around the world? Where is the joy in Ohio being put out and killing your own single, Teach Your Children, because we thought it was more important to let them know that we are killing our kids for their God-given right to protest what their government was doing in their name?”

When it came to writing Wild Tales, Nash felt it important to tell his life story in an unvarnished way. “When I reached the point where I was going to write my autobiography I realised I was going to have to tell the truth,” he says.

“We all have our own truths. Stephens Stills thinks the first time we sang together was in Mama Cass’s kitchen; it wasn’t, it was in Joni’s living room. David knows it and I know it, but we all have our own truths. When I wanted to put out Wild Tales I decided I would tell the truth, and that’s what I did.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere were, he admits, parts that were difficult to write. “Basically I was uncomfortable about how David was ruining his life with drugs, that was a sad point for me, but I talked about it and I didn’t say anything that hadn’t been in David’s two autobiographies and countless interviews where he talked about his life.

“Wild Tales was a pretty interesting thing and I’m glad I’ve got it out of the way.”

This year is CSNY’s 50th anniversary but Nash is emphatic that there won’t be any reunion to mark it. “No, not at all,” he says. “You have to love each other and like each other to be able to make music together and we don’t, so it’s OK.

“The point is if we never make another note of music, look at what we did in the last 50 years.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAside from music, Nash has long been a keen photographer and collector of photographs. He puts his interest down to what photographs can say about a person. “In a really strange way I can hear photographs and I can see music,” he says. “There’s a very famous photograph by Ansel Adams called Moonrise Over Hernandez. When I look into that image and I look into the grey clouds I can hear violins play, if I’m not in the foreground where it’s all dark and it’s all bushes and trees, I can hear the cellos.

“I don’t write classical music but if I hear a different chord and I say to the orchestra leader, ‘Can you make that a little more purple?’, that’s what I want, that makes it a minor change.”

Graham Nash plays at Victoria Theatre, Halifax on July 17. www.grahamnash.com