Nostalgia on Tuesday: Picturing tragedy

The world’s first newspaper full of pictures was the Illustrated London News, which appeared on Saturday May 14, 1842 though illustrations had been used on an irregular basis before that time particularly in The Weekly Chronicle. During its early years, the ILN despatched armies of artists to newsworthy events and they produced highly dramatic pictures probably relying only on eyewitness accounts for much of the detail they showed.

ILN artists and journalists were sent to the Hexthorpe rail crash near Doncaster on Friday September 16, 1887. The tragic event occurred during what is known as the town’s St Leger Race Week on the day of the Doncaster Gold Cup.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe railway traffic into the town during that period was on a huge scale. At any time Doncaster was a busy station but in race week the traffic was multiplied many times. The trains were crammed with passengers and special excursion trains operated carrying thousands. On Friday September 16, there were about 40 excursion trains expected in Doncaster.

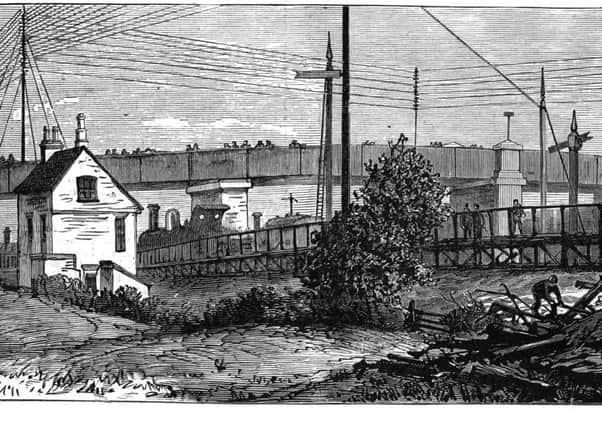

About a mile to the west of Doncaster’s Great Northern railway station, on the Manchester, Sheffield & Lincolnshire line, there was the lengthy ‘ticket’ Cherry Tree Lane platform at Hexthorpe, used only on extraordinary occasions, particularly during race week.

The platform was between two bridges, which spanned the line a few hundred yards apart. The bridge west of the platform was Hexthorpe Bridge and just beneath it the line curved so that at a very short distance away the ticket platform was not visible from the cab of an approaching engine.

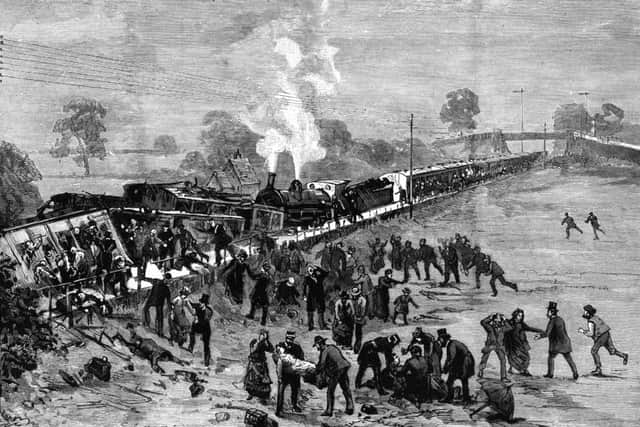

Among the numerous excursion trains run that Friday was a Midland company train from Sheffield. It contained a number of well-filled carriages, mainly with third-class passengers. At 12.15pm it paused at the Cherry Tree Lane platform for the collection of tickets, by the train guard, several porters and others. Almost without warning, an MS&L train dashed round the western curve and smashed into the last vehicle of the Midland train at the platform. The engine telescoped into the last carriage, reducing it to matchwood; the carriage in front of that was destroyed bodily, the two end compartments of the third carriage up were knocked away and extensive damage was sustained to the remaining vehicles.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShrieks of agony and terror filled the air, splinters of wreckage flew on all sides, a great portion of the platform railing was carried away and there was panic alike in both trains, and among the company’s servants on the platform. MS&L officials, who happened to be in Doncaster, hurried to the scene along with a number of police.

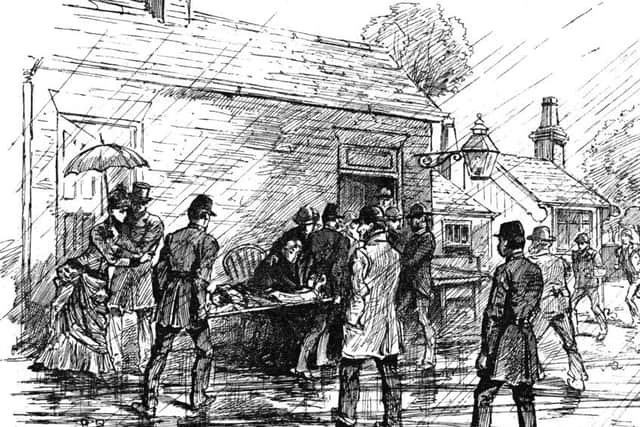

Reporting on the tragedy, The Yorkshire Post said the work of releasing the dead and rescuing the injured from the debris was ‘of the most painful character’. The dead were shockingly mutilated – some of them beyond identification. The bodies of both dead and injured were in some cases wedged in between portions of debris, which had to be cut away before those imprisoned could be released.

A remarkable incident occurred concerning a woman and her baby. They were the only occupants of one compartment. The mother was dead while the baby on her knee was uninjured and smiled in the face of a rescuer. The bodies were laid in a field and then removed to a shed.

A number of medical men were soon on the spot, rendering all the assistance they could and amongst them was Dr Penny, inset, resident house surgeon at the hospital. The injured were eventually removed to Doncaster Infirmary in waggonettes, cabs and any vehicle that was available. At the infirmary, which normally provided a mere 24 beds, the facilities were stretched to their limits. More nurses were also called upon.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe train which caused such havoc was the MS&L ordinary from Liverpool to Hull by way of Barnsley. Its driver was Samuel Taylor, 39, of Liverpool. The section of line between Hexthorpe Junction and Cherry Tree Lane platform was considered one ‘absolute block’ section of line for signalling purposes.

In normal circumstances only one train would be allowed into the section at a time, but Cherry Tree Lane platform, used intermittently for race traffic, complicated the signalling arrangements.

Unusually, ‘permissive block’ signalling (more common to goods yards) was used to allow more than one train into the section at a time, but men with signalling flags were installed at intervals.

Shortly before the crash, two trains were in the section, one at the platform, and another waiting. After the first moved off, the Midland train approached the platform. A third train (the MS&L Liverpool-Hull express) was allowed into the section and the crew, apparently unfamiliar with this area, proceeded under the impression of normal conditions. The first flagman, who according to the driver and fireman made no signal, was passed and the second gave a signal that was not understood by the fireman.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBecause the platform was beyond a curve, the Hull express driver had only 250 yards to stop the train at 35-40 mph.

The crash claimed 25 lives and 60 were injured. The driver and his fireman were sent for trial at York on charges of manslaughter but with support from ASLEF were acquitted on account of contributory negligence by the guards, no cord communication and the conflicting nature of the signals.