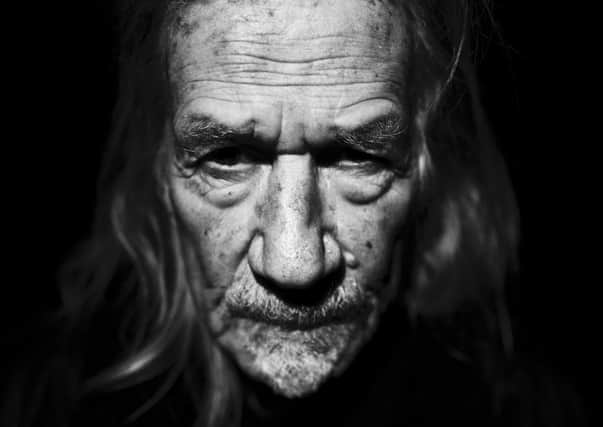

Penny Rimbaud: ‘We’ve moved into much more of an accepted censorial world’

But his new album How? takes him back to an early inspiration: Allen Ginsberg. Rimbaud, 77, says he arrived at his poetry “via Walt Whitman...who I would say is my greatest influence, I was introduced to him in my late teens and that then led to the American Beats”.

Following a live recital of Ginsberg’s most famous work Howl at a club in 2003, Rimbaud was invited to perform the poem again at the London Jazz Festival but ran into problems with copyright holders HarperCollins, part of Rupert Murdoch’s publishing empire. “It was extraordinarily difficult,” he says. “I wrote to City Lights and then to HarperCollins and got nowhere. When I found out HarperCollins was owned by Rupert Murdoch I thought, ‘sorry, I’m not prepared to buy into that’. Ginsberg would have crawled out of his grave in anger if he knew that.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdKnowing that he had the gig booked, he decided he had “got to rewrite” the poem in his own style. “I felt it was actually pertinent to do so,” he says, adding: “I also found out at the same that George Bush was coming to the UK and I learnt a big march (to protest against the Iraq War) was being planned on the day of the gig, so that was the inspiration to use the sentiments of Howl against a different opponent. I basically chose corporate capitalism, but most notably its effects on the arts, how the best minds of my generation were bought up with the dollar. I saw that happening constantly in the same way as Ginsberg is constantly repeating the defeat of progressive thought in Howl. We’ve moved into much more of an accepted censorial world and that is what I was really attacking mostly, but it also gave me an opportunity to take a blast at all of the illnesses of the 21st century.”

This recording of How? dates from 2017. Rimbaud decided it was apt to release it now. “Without wanting to be vain, most of my works seems to grow in pertinence. I would certainly say that about Crass’s stuff which at the time seemed pretty radical but now seems to prescient that it’s horrifying. How? is one I’ve constantly gone back to because it always seems relevant, I often ad lib during it when I feel there’s something I should notably comment on that’s going on at the moment, it gives me that freedom although it is actually one of the most exhausting pieces of work that I’ve written to perform, it’s non-stop. I think the growth of corporate capitalism has been incremental ever since. It is now going through what maybe is a form of stoppage, which I sincerely hope is one that we can creatively work ourselves around. I suppose it was about that in a way – all is not lost.

“At one point it was scheduled to be released next year, and I thought, ‘no, we’ve got to move this forward to the front of the stack’ because it in some way or other is making a commentary about what’s going on, certainly it’s making commentary on why it’s going on in the manner it is, and I knew with liner notes I could up it into the current crisis.”

The Covid crisis has prompted much discussion about reordering society. Rimbaud feels such debate is at the heart of How? “It’s been at the heart of what I’ve said all my creative life,” he says. “The actual tactic might change – in Crass we came close to being a sort of revolutionary outfit in the true sense of the word, certainly our aims were revolutionary, to create a street revolution out there – since then I’ve become much more inward, much more contemplative, and come to understand and believe that no revolution can come before the great inner revolution, the revolution of self, which then presents new, profounder avenues into global change – adopting and adapting an essential belief that all governance is wrong, all work is slavery, actually all of the old anarchist cant, but trying to find new settings and positive settings.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“So often revolution can turn into nihilistic or negative thinking, as it did with Crass. It was very much a them and us situation. In How? I was trying to take a broader picture. The first two parts are about ‘this is how it is’ and then the second two parts are very much ‘this is how it could be’, with humour and love, every bit as much chanting the desperate need for change, just in a different setting.

“I’m not a conceptualist, in the sense that I don’t think ‘oh, I’ve got to do that’, I do stuff because that’s how I feel it, that’s how I perform it, that’s how I write it. I can’t do things if I don’t feel, and I certainly never do anything to order. My work is always sort of stream of consciousness, and then added to when I perform it.”

The values of self-sufficiency and free-thinking are key tenets of Dial House, the anarchist-pacifist community that Rimbaud and his partner, the artist Gee Vaucher, helped to establish in the Essex countryside in 1967. Rimbaud, however, says he can trace the lineage of his thinking back much further, to childhood, and the strained relationship he had with his father, who had fought in the Second World War.

“When I was about five or six I took a book out of my parents’ library about the (Nazi concentration) camps. An innocent young kid opens the pages and there they are – all the corpses in the pits. I didn’t meet my father until I was about three, and when I did meet him I didn’t like him very much because he was destroying my intimate relationship with my mother. This person had turned up, so I took exception to him and I took strong exception to his reference to the ‘real world’. I thought the real world was in my mum’s arms, not this thing he was talking about, and when I saw the camp pictures I remember thinking, ‘That’s what he was up to, no wonder I don’t like him’. A kid doesn’t know or understand, he didn’t talk about them and I didn’t dare ask him, so that delusion was with me for a little while.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“At the age of five or six I determined I don’t like that real world. If the real world is all bodies in pits and grumpy old men, I don’t want anything to do with it. I did spend the rest of my life, up until today, trying to find ways to challenge, reject, totally demolish any way which I don’t have to belong to such a horror.

“I was introduced to Zen thought when I was in my early teens, etcetera etcetera, all of these things started giving me great meaning or at least escape routes from a media material world. My whole life has been trying to make better something as a very early child I realised was just downright horrible. That’s a simple word ‘horrible’, but that’s what it is and that’s what it remains. It’s got even more horrible in so many ways and unjust and unfair, mean and cruel and all the rest of it.”

How? is out now on One Little Independent.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.