Pleasure principal: Stanley Spencer at the Hepworth

The show, the first major UK retrospective of the artist’s work in 15 years, brings together more than 70 significant pieces spanning Spencer’s 45-year career, including a series of rarely seen self-portraits as well portraits of people close to him and important works from private collections that have not been shown in public, in some cases, for decades.

Exploring the recurring themes in the artist’s work – religion and sexuality, nature and industry, work and leisure – the exhibition presents not only a rich and hugely rewarding overview of Spencer’s versatility as a painter but also a fascinating glimpse into the wide scope of his artistic imagination.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“What I really wanted from the whole show was to give people an insight into Spencer’s creative processes,” says curator Eleanor Clayton. “He wrote about his own work all the time – there are over a million of his words in the Tate Archive – and one of the things he says is that people love the idea of an incomprehensible genius, but he wants people to know his thought processes. He always said that he wanted people to read his paintings like they read a book.”

The self-portraits, which are presented all together chronologically in one room, starting with his first-known student self-portrait begun in 1912 to his last made only months before his death, offer an affecting perspective on Spencer’s unflinchingly honest view of himself, as well as a sobering reflection on the ageing process. One, painted a few years after the First World War in 1923, is particularly moving.

In 1915, at the age of 24, Spencer volunteered to serve with the Royal Army Medical Corps and the following year he was sent to Macedonia. In 1917 he volunteered to be transferred to an infantry regiment – in all spending two and a half years on the front line before being invalided out of the Army due to recurring malaria. His older brother Sydney was killed in action in September 1918.

Returning to live with his parents in his beloved home town of Cookham in Berkshire, he found it difficult to continue with his work, stating that “it is not proper or sensible to expect to paint after such experience”. His First World War paintings are very powerful and it is these for which he is perhaps best known, but despite dying relatively young at the age of 68 in 1959, Spencer has a huge body of work.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis early influences were the religious paintings of early Italian artists such as Giotto and Botticelli whose paintings he saw at the National Gallery in London while he was a student at the Slade School of Art. These artists were known at that time as the “Italian Primitives” and by the time Spencer finished his studies in 1912 he had become one of the several artists referred to as the “Neo-Primitives” because of their enthusiasm for the Early Renaissance painters. On display in the exhibition is Botticelli’s Three Miracles of Saint Zenobius, on loan from the National Gallery, placed alongside one of Spencer’s so-called “visionary” paintings, Zacharias and Elizabeth, and the similarities are strikingly apparent. Like Botticelli, he placed biblical stories in a contemporary setting and costume – in Botticelli’s case it was 15th century Florence and in Spencer’s 20th century Cookham.

“Spencer was very religious throughout his life,” says Clayton. “But it was not about organised religion; he developed his own unique religious beliefs – he felt people should find their own relationship with God and he certainly felt there should be more of a connection between the spiritual and the physical.”

This is reflected time and again in his work. A Village in Heaven, for example, presents an “end of days” scenario where there is no Hieronymus Bosch-style apocalyptic judgement but instead a gentle idyll set in a village square where the villagers dance, play, embrace, caress and take pleasure in each other.

“When you consider what Spencer went through during the war, you can understand why he wanted everyone to be happy and to love each other,” says Clayton. “He wanted to focus on life and love and joy and sex. He saw joy everywhere.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

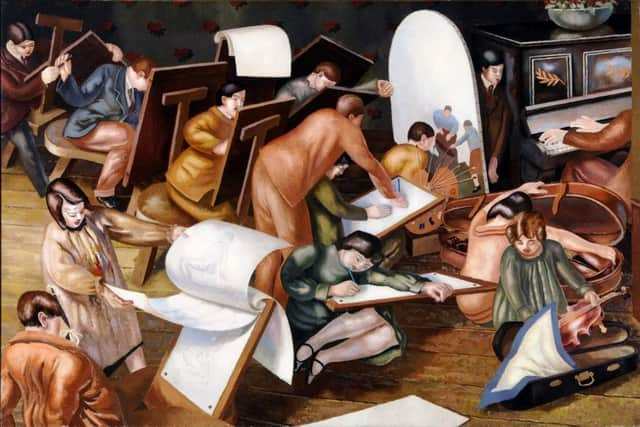

Hide AdIn 1929 Spencer was invited to propose designs for posters to be produced by the Empire Marketing Board on the theme of Peace and Industry. He produced two alternative drawings and adapted one of them into five separate panels, now all owned by several private collectors, four of which are reunited in the exhibition for the first time in 36 years. “His proposal was actually rejected,” says Clayton. “But his dealer was so impressed by them that he put Spencer forward for a commission with Cunard for a painting for the ballroom of their new ship The Queen Mary.”

His proposal was to create a depiction of the men building the ship which the commissioning board rejected. However, it did lead to the offer of work as a war artist during the Second World War painting Glasgow’s shipyards. The resulting monumental paintings, known as the Shipbuilding on the Clyde series, capture a key moment in Britain’s history.

“Spencer was a committed Socialist,” says Clayton. “Which was another legacy of the First World War when he became aware of how many of his fellow soldiers didn’t have access to the music and art that he so loved.”

The exhibition, which has been visited by Spencer’s two daughters, Unity and Sharin, took around a year to put together and Clayton spent many hours researching Spencer’s vast written archive. “It has been so rewarding,” she says. “And to be able to show people the breadth of his practice and painting style and how he saw the world is wonderful.”

• Stanley Spencer: Of Angels and Dirt, The Hepworth Wakefield to October 5. hepworthwakefield.org