The Price of Coal

Before 1700, coal production annually amounted to around 2.7 million tonnes and came from two types of mines: small scale drift mines and bell pits. The Industrial Revolution encouraged deeper and deeper mines with shafts dropping hundreds of feet into the ground. Once a coal seam was found the miners dug horizontally following it. There was little coal discovered in the South but it was plentiful in the Midlands, the North, the North East and Scotland.

Evidence of coal mining in Barnsley during the late 14th century is proved by permission being granted by members of the powerful Fitzwilliam family for leases and grants for coal getting. This was small-scale mining with coal being burnt as fuel locally. Then, during the latter half of the 16th century there was an expansion in the use and mining of coal, as well as ironstone, to meet local industrial needs.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFurther development in Barnsley’s coal industry was restricted until stocks could be transported more easily by canals, particularly when the Dearne & Dove Canal was completed in 1796. Further assistance was gained as the British railway system expanded from the 1840s onwards.

The deeper collieries were sunk, the greater the risk to miners’ lives. Besides flooding and underground collapses, explosive gas (firedamp) was often encountered and a spark from a miner’s pick axe or candle could have disastrous consequences.

For a number of years Barnsley’s Oaks or ‘Great Ardsley Main’ Colliery, dating from at least the 1820s, had the worst mining disaster record in the world. Around mid-day, on June 11, 1845 a firedamp explosion killed three men – all in their 20s – at the Oaks Colliery, owned by Firth, Barber & Co on land leased from Micklethwaite of Ardsley Hall. Amongst the injured were three children. The explosion was allegedly caused when one of the deceased took a lighted candle too far into the workings despite having being told to use lamps instead.

Just under two years later, at around 3pm on Friday, March 5 1847, there was another Oaks colliery firedamp explosion with the loss of 73 men and boys. One newspaper report stated: ‘Several persons near the mouth of the pit were alarmed by a terrific explosion from the shaft, which was followed by an eruption of smoke, timber, coal, stone etc, resembling the eruption of a volcano.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

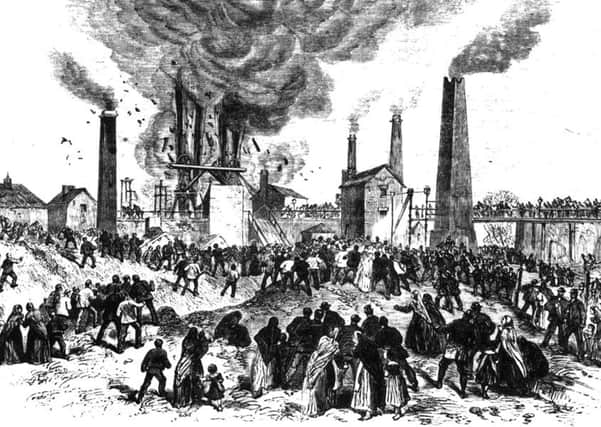

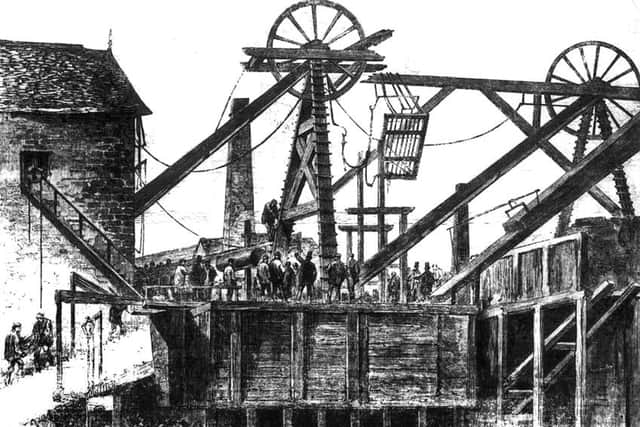

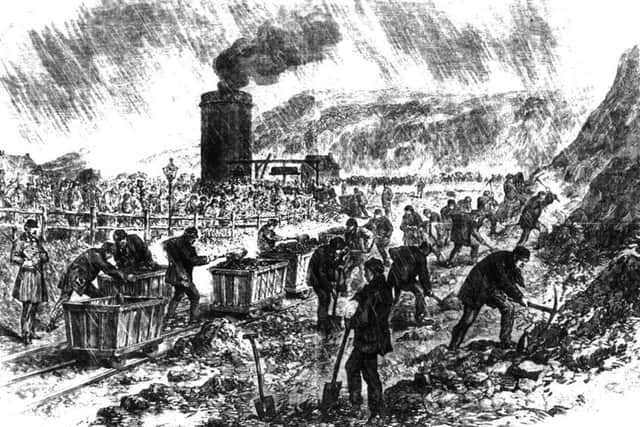

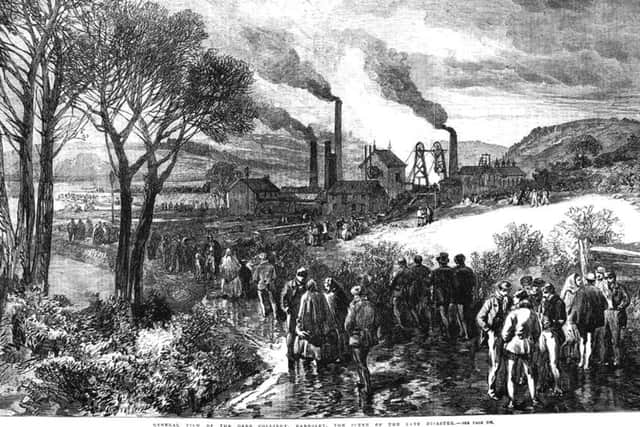

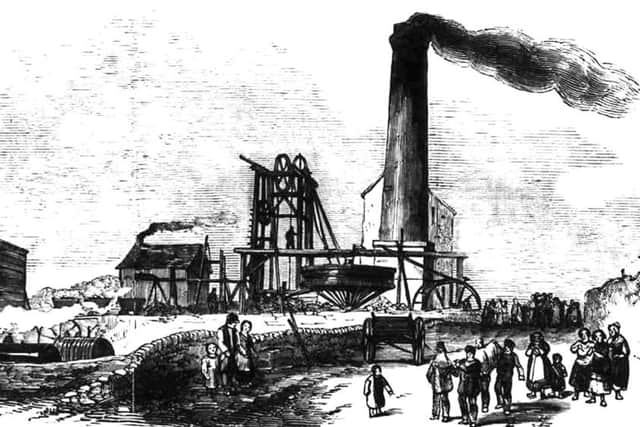

Hide AdThe Illustrated London News sent artists to Barnsley and a number of their highly dramatic images illustrated a full page article entitled ‘Terrific Explosion and Loss of Life at Barnsley’.

Once again, the cause of the explosion was put down to a naked light in an area where flammable gas was known to exist. Following the disaster, noted geologist and palaeontologist Sir Henry Thomas de La Beche, along with a mines’ officer (appointed under the 1842 Coal Mines Act), arrived in Barnsley to investigate. Their report recommended government inspection of mines but this was not to be established for years.

After the 1847 explosion, the pit was virtually closed down, although further shafts were sunk nearby and coal production began around 1851.

In mid-1856 the 400 strong Oaks workforce went on strike claiming safety was being ignored by pit management. Brian Elliott in South Yorkshire Mining Disasters (2006) notes this ‘was two years before a properly organised miners’ union was formed in Yorkshire, when fraternal organisation and representation was weak’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe strike lasted ten weeks before the miners, facing starvation and eviction from their homes, returned to work. Industrial relations were strained during the ensuing years, with another bitter dispute in 1864 where striking miners were evicted from colliery-owned houses.

In December 1866, several explosions rocked the colliery, killing what is now believed to be 361 men and boys. In terms of numbers killed, the tragedy remained Britain’s worst mining disaster until 1913 following the explosion at the Universal Colliery, Senghenydd near Caerphilly in South Wales, where 439 died. The Oaks disaster remains the worst in an English coalfield.

Hoyle Mill village nearby lost nearly all its male population including a man named Wilkinson and his four sons. The Illustrated London News once more sent artists to capture the scene, and several of their works may be seen here.

Learning of the tragedy, Queen Victoria sent a telegram to the Oaks which read: ‘The Queen desires to make inquiry as to the possible extent of the explosion, and whether the loss of life is as serious as reported’. She pledged £200 to a relief fund.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe inquest heard that management had been made aware that gas was present in the colliery workings only days before the explosions.

But the verdict on the cause of the tragedy, or the source of the first ignition, was inconclusive.

Afterwards, the two shafts at the Oaks, becoming known as the Old Oaks, were abandoned and new shafts sunk three quarters of a mile away at Ardsley became known as New Oaks. Following further shaft sinkings, amalgamations and developments the pit became Barnsley Main. Sadly, further explosions and loss of life would occur until closure of the pit in July 1991.

A memorial to those killed in the 1866 disaster was erected at Christ church, Ardsley, in 1879 and a second one in Doncaster Road, Barnsley, during 1913.