Summit or nothing: How we took mountaineering to new heights

“What I’d always loved about climbing was that unlike most other sports it doesn’t need a result to justify the reward. It’s just you against the mountain and when I knew that it was almost over for me, I just wanted to see some of my favourite routes one last time.”

The Parkinson’s diagnosis, which came as Mark returned from another memorable climbing trip to Spain, was particularly cruel for someone whose life has always been centred on the outdoors. He admits that in the months that followed he experienced the dark clouds of depression, but while it has robbed him of the ability to take part in the sport it has also given him renewed focus on other projects.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne has been to write his memoirs. Wild Country – The Man Who Made Friends has just been published and it chronicles not just the mountains he has climbed, but the part he played in bringing to market a little piece of sporting equipment that revolutionised mountaineering and saved countless lives.

“The reason I decided to write the book is because there is so much I can’t do,” says Mark at his home in Dore, near Sheffield. “Writing is one of the things still in my power and I guess I also thought I had something to say. There are so many books published by mountaineers and a lot of them can get bogged down in the minute details of individual climbs. I wanted this to be different.”

And different it is. It was back in the 1970s that Mark first met Ray Jardine, who was not only one of the best climbers in the world, but who also harboured a secret invention. “I’d known Ray for two or three years, before he showed me the device he’d made that he believed would allow him to climb harder and faster,” adds Mark. “Those early prototypes were an odd selection. Some were beautifully made with polished aluminium, others were much more rough and ready, but I immediately realised their potential.”

Those early spring-loaded camming devices would become known as Friends and today few mountaineers leave home without them. Put simply, they can be placed into small cracks along the rock face and, should a climber fall, they will hold their weight on the end of the rope.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Ray had showed them to a few other people, but he hadn’t been met by a whole lot of enthusiasm. Part of the problem was working out how to manufacture them for a sensible price, but I knew that if we could do that we would have something that could really change mountaineering.

“There were other bits of equipment being used, but pretty much all of it was unreliable and that’s not what you need when you a few hundred feet up a cliff face.”

Returning to the Peak District where he had a job with the National Park Authority, Mark began the long and often frustrating process of bringing Ray’s idea to market. “I was not an engineer, a designer or an accountant, but I think Ray was getting desperate and I think he probably thought I was his last hope.”

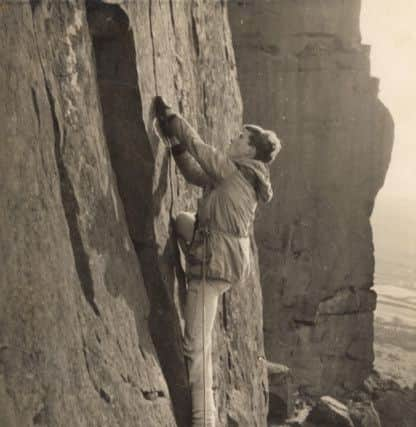

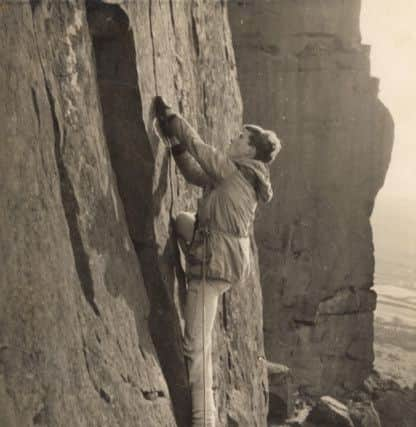

The trust paid off and, having secured the support of a manufacturer and a friendly bank manager in 1977, the first Friends began to roll off the production line. The only problem was no one else knew about them. “That’s when I decided to write to Tomorrow’s World,” says Mark. “I told them I had an invention which ticked all their boxes and a few months later I got a call. It was mid-December and in the New Year I found myself hanging off Millstone Edge in Dark Peak with a camera pointing straight up at me.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I knew should anything go wrong I would destroy both it and me. As I jumped the ground rushed to meet me, the rope tightened, the air was knocked out of my lungs and I came to a halt about 8ft above the camera.”

When the footage went out a month or so later, it was the biggest free advert that Mark and Ray could have hoped for. “It’s hard to remember now just how popular and influential Tomorrow’s World was. Before our piece went out only 14 people in the world knew about Friends and 13 of them were in America. But after our film, which lasted four minutes and 14 seconds, it seemed like the world knew.

“That February we had sold precisely 18 Friends. Within six months we were selling in 16 countries and within eight months we had sold 8,000. As sales graphs go it was pretty spectacular.”

Mark’s own passion for the mountains, which has taken him from the Peak District to El Capitan in Yosemite National Park and the Himalayas, began in a cinema on the outskirts of Manchester.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Like many youngsters I was taken to see the film of the first ascent of Mount Everest in 1953,” he says. “Going to the cinema was a big deal in those days and I can still remember much of the detail, from the porters struggling with, of all things, a piano to the climbers packing supplies. From that moment I wanted to be a climber and I begged my father, who was a keen fell walker, to take the family to the Lake District the following summer.”

By the age of 11, Mark had completed his first ascent of a small cliff in Langdale called Scout Crag and his appetite for adventure never really waned. He spent two years working for the British Antarctic Survey where he was base commander of the UK’s largest and most southerly scientific station at Halley Bay and, keen to pass on his love of the outdoors to others, he also founded the Foundry Centre in Sheffield, home to one of Britain’s first climbing walls.

While Parkinson’s means he can no longer climb, one of his proudest achievements of recent years is his spell as president of the British Mountaineering Council. Like many member organisations, the BMC, which was founded in 1944, had become mired in bureaucracy and dragging it into the 21st century was arguably as big a challenge as any of the peaks he had previously scaled. “My reason for wanting to be president was half selfish, half altruistic. Parkinson’s was causing a slow, but steady deterioration in my ability to climb and I was glad to have the opportunity to do a job which kept me involved in the mountaineering world.

“It wasn’t easy, but we did reform the organisation and removed the block voting system which had given the big clubs all the power.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile Mark’s condition causes him to be unbalanced and he says his voice is starting to sound “thin and dry”, he knows that for someone diagnosed 18 years ago he is faring pretty well.

“I’m sure a lot of that is down to luck, I respond to the drugs pretty well, but I also think having a good attitude helps. I am sure had I sold the business earlier I might have come close to being a millionaire.

“But while there are many things I would like to have accomplished, being filthy rich is not one of them. When I am having a bad Parkinson’s day and feeling a little hard done by, I try to remember all the good times and there have been many. Yes, mountain climbing is risky, but it is also the most rewarding, powerfully seductive thing you can do.”

Wild Country – The Man Who Made Friends by Mark Vallance is published by Vertebrate Publishing, priced at £14.95.