Helena Whitbread: “I liberated Anne Lister from the archives.”

That someone turned out to be Anne Lister. “I had heard of her but I knew nothing about her other than the fact she used to live at Shibden Hall in the early 19th century,” says Helena.

“I asked the archivist if I could read her letters so he put them up on the reader for me, but they were in this trellis-style form and I thought, ‘that looks difficult.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“But then he said, ‘do you know she kept a journal?’ And those seven words sparked my whole interest in her.”

Anne Lister was a Halifax-born landowner who inherited the Shibden estate in 1836. She was, of course, far more than that. She was a pioneering mountaineer, intrepid traveller and entrepreneur, and had an interest in languages and science.

She was also a lesbian and engaged in a number of passionate relationships with women throughout her life, which she chronicled in her secret diaries.

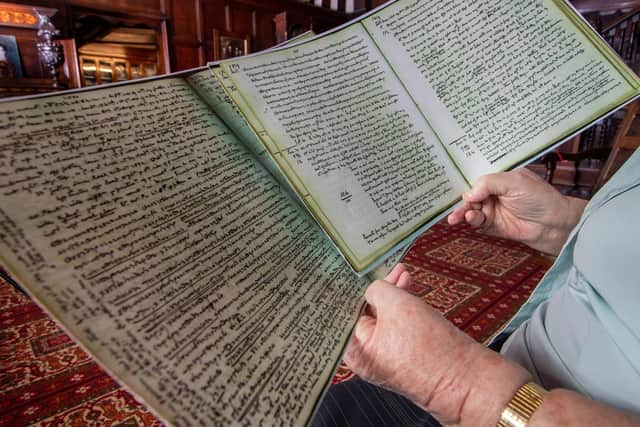

Anne wrote her journals in what she called her ‘‘plain hand’’, her ordinary writing, and when she wanted to write about anything private she did it using what she called her ‘‘crypthand’’ – a system of symbols that she devised.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen Helena, now 89, heard about this she was intrigued. The archivist photocopied the key to the code and Helena took 50 pages home with her and began transcribing them.

It took her five years to trawl through the journals which consisted of 27 books, 7,700 pages and more than five million words – about 15 per cent of which were in Anne’s cryptic language.

The journals had originally been transcribed in the late 19th century by John Lister, a relative of Anne’s and the last member of the Lister family to live at Shibden Hall. He and his friend Arthur Burrell, a Bradford school teacher, cracked the code but were shocked by Anne’s lesbian admissions, so much so that Arthur wanted to burn the journals. Thankfully, John stopped him though he kept the journals hidden, afraid of the public scandal that would ensue should they ever see the light of day.

However, nearly a century later, Helena felt there was an audience for Anne’s diaries and found a publisher.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe first book, The Secret Diaries of Miss Anne Lister: I Know My Own Heart, came out in 1988, followed four years later by the second volume, No Priest But Love, which carries on where the first volume left off – focusing on a two-year period from 1824 to 1826.

The books garnered some interest in the academic world but never sold many copies. And then came Gentleman Jack. Sally Wainwright’s TV adaptation of Anne Lister’s life was aired last year and became a hit on both sides of the Atlantic.

“For more than 30 years these works laid dormant and then all of a sudden Sally Wainwright’s epic series came out and interest has just mushroomed,” she says.

Helena’s books had been selling modestly up until a year ago. “My editor rang me up after the first episode of Gentleman Jack had been shown in America and she said up until the end of March my books had sold 69 copies, which was about average. But in the first week after Gentleman Jack had gone on air they’d sold 2,500 copies.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy the end of June she had sold more than 10,000 copies. Along with Jill Liddington and Anne Choma, who have both written about Anne Lister’s life, Helena has become an expert on a woman described as “the first modern lesbian”.

When Helena’s books first came out (a new version of No Priest But Love was released on Thursday) they weren’t universally welcomed, with some people concerned about the impact they might have on the reputation of such a prominent local family. But following the success of Gentleman Jack (a new series has been commissioned), the town has been quick to embrace her story with Anne Lister now a magnet for tourists.

At Shibden Hall, visitor numbers trebled between May and August last year, when the series first aired. In August, more than 14,000 people passed through the museum compared to just over 2,500 in August 2018.

Last year’s Anne Lister Weekend, which saw fans from around the world descend on Halifax, sold out quickly, and a five-day event celebrating the fascinating history of Anne Lister and Ann Walker, featuring talks and events, was due to take place next month.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnne Lister became a household name almost overnight and he connections to Halifax run deep – she was baptised at the Minster and was a regular worshipper there, though by all accounts she wasn’t overly enamoured with her hometown or many of the people that lived there.

“Anne didn’t actually like Halifax, she thought the people there were vulgar,” says Helena. “It was a market and post office to her, though she did have to socialise with people in the town.”

Despite her social standing and the fact she was effectively a member of the landed gentry, she wasn’t immune from verbal or physical abuse – though she was more than capable of looking after herself. “Men would say rude things and one man going up New Bank tried to put his hand up her clothes and she rounded on him and he was so frightened he ran away.”

Today, though, Halifax is proud to call Anne Lister one of their own. And Shibden isn’t the only place where the Gentleman Jack effect has been felt. Increased income has been reported from museums, local businesses, and hotels, and visits to Halifax’s Bankfield Museum, where costumes from the series are on display, have almost trebled.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd at the Piece Hall, shops are selling memorabilia that date from Anne’s time, as well as artwork and merchandise.

For Helena, Anne Lister is finally being recognised for the pioneering woman she was. “She was so fearless in an era when there was no language for lesbianism. She said, ‘I am an enigma even unto myself. And I do excite my own curiosity.’ She really thought no one else had her kind of sexuality. Today, women aren’t afraid to come out and express who they are and how they feel, but she couldn’t do that. And it was her fearlessness and courage that I found so fascinating.”

Her importance goes beyond her sexuality, though. “She’s a role model. I get messages from women all over the world saying how inspiring she was and how she’s given them courage in their own lives and has helped women all over the world bond with each other, so she’s had this wonderful cohesive effect. She’s shown women today that they can do things and they can be brave.”

When Helena published the diaries she lit a slow fuse that exploded three decades later. “I like to think I liberated her from the archives,” she says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Anne Lister has kind of trickled through the decades and now she’s become a global icon, which I think is wonderful.”

The Secret Diaries of Miss Anne Lister – No Priest But Love, edited by Helena Whitbread, is published by Virago and out now priced £8.99.