Martin Bell: University of Leeds' Special Collections celebrates catalogue of poet who hated the city

When you consider that the late poet Martin Bell did not particularly like Leeds, it is amusing to think how hard archivists have worked to preserve his contribution to the city and literature. They don’t seem to mind one bit.

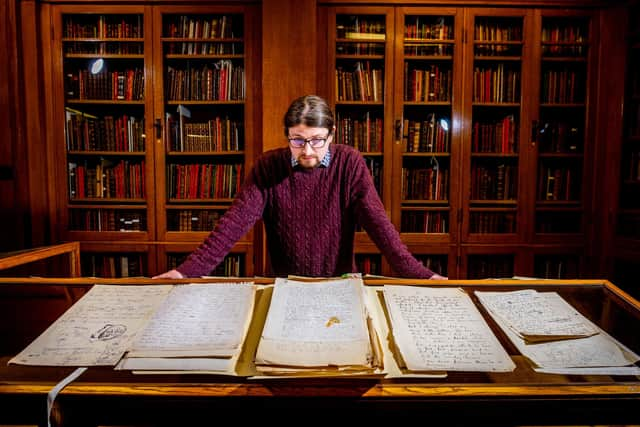

“He was not a fan,” says Sarah Prescott, a literary archivist working for the Special Collections at the University of Leeds, as she and colleague Jon Gilbert describe their impassioned efforts over recent years to preserve his legacy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Second World War veteran was a prominent member of The Group poets during the 1950s, proving a major influence on younger writers including Peter Redgrove and Peter Porter, before taking up a Gregory Fellowship at the university in 1967.

Bell might have hated it – and possibly even “enjoyed hating it a little bit,” says Sarah – but he lived in the city for the rest of his life until his death in 1978 after years of alcoholism.

The archivists, though, recently held an event to launch the catalogue of the Martin Bell papers, the largest single collection of his manuscripts and correspondence.

It was a project which felt necessary in order to recognise a poet whose esteem among venerated contemporaries and friends such as Anthony Burgess is not reflected more widely today.

Why has he been neglected?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne reason might be that, despite being a key member of The Group, his work “exists between disciplines”, says Jon.

Also, he only brought out one book during his lifetime, the Collected Poems - an odd publication in itself, given that there were no prior releases.

Sarah adds: “Quite a large factor (in his neglected legacy) would be the chaos and poverty of his final years and a lot of that was due to alcoholism that he suffered from.

“As you can imagine, that made publication and remunerated work very difficult for him. And the evidence of that in the archive is one of the most compelling things, I would say. But what comes through, and what the real strength of the archive that we now have in Leeds is that it shows that even in those difficult years he was an incredibly fruitful writer.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBell was born in Hampshire in 1918, attending University College Southampton, where he read for an external London Honours degree in English, followed in 1939 by a Diploma in Education. He went on to fight during the war with the Royal Engineers in Lebanon, Syria and Italy, according to university materials. Then he returned to work as a schoolteacher in London for some years before a chance meeting with Redgrove, who invited him to join The Group.

Bell’s poetry reached a wider audience during the 1960s through the Penguin Modern Poets series, and in 1967 he published his Collected Poems, 1937-1966.

His work was “insightful, at times bitingly satirical” and “it's often hard to tell when Bell’s being ironic and when he isn't, and I think he enjoyed that,” says Jon.

“I think what he gets from the French realist poetry is really vivid imagery and a freedom that perhaps the other poets of his time didn't really express,” he adds. “And there's a lot of dry humour in there as well.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe wrote little about his experience in the war with the exception of Reasons for Refusal, about choosing to not buy a memorial poppy.

Bell met his partner Christine McCausland at the 1965 Edinburgh Festival and later lived with her in Leeds, where he was also given use of a house during his fellowship – a scheme to encourage arts participation, named after Eric Craven Gregory – and would hold poetry discussions in the Fenton pub near campus.

After serving his fellowship, he ran a small class in poetry at Leeds School of Art.

Bell’s literary work during his later life includes the blistering unfinished sequence The City of Dreadful Something – his own way of immortalising Leeds – and translations of French surrealist poetry.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis own poems from this period were often incomplete and many were unpublished during his lifetime, while his final years were spent in poverty.

Efforts to develop an archive of Bell’s work and correspondence in Leeds had been difficult until, after the death of McCausland – who had moved to London in the early 1970s , but stayed in touch with the poet – manuscripts and letters were bequeathed to Special Collections a few years ago.

“When we came to look through them, we saw that this was the lost archive,” says Sarah.

The letters, of which there were hundreds, “really get into the meat of who he was,” she adds.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“People's archives can reflect who they were and their circumstances and that's certainly true of the Bell stuff because it was pure chaos - boxes of chaos with no order, and it was just so difficult to discern what it was and to think about how we could make it available.”

Jon, a postgraduate teaching assistant who is also an intern with the collections team, got to work making sense of the files. It turned out that they offered unprecedented insight into Bell’s later years, including the disorder of his life and tragedy of his struggle with alcoholism. Files also include correspondence with luminaries such as Philip Larkin, Peter Porter, Peter Redgrove, Philip Hobsbaum and George Szirtzes.

Now the catalogue will be available for both students and others who have an interest to see in Leeds – which Jon jokes is a sort of “poetic justice”.

Sarah says: “It is such a big deal for this to exist and for us to have it and for us to make it available. That’s how reputations are restored, I would hope. People can use this, understand Bell and his significance - and write about it.”

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.