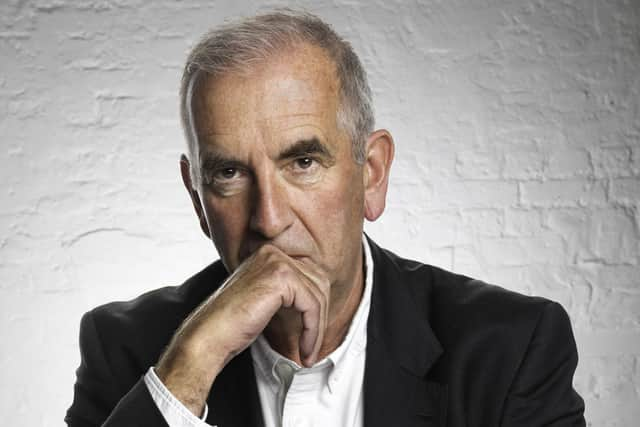

Robert Harris appearance at Harrogate literature festival: How a Twitter post inspired his English Civil War thriller Act of Oblivion

The circumstances here are true, the only fiction is that of Nayler, a made up character in the latest historical thriller by Robert Harris, Act of Oblivion - a story inspired, incongruously, by a Twitter post he saw about the “greatest manhunt of the 17th century”.

Harris will discuss his 15th novel at the Crown Hotel from 4.30pm on the final day of the Raworths Harrogate Literature Festival on Sunday, October 23, and will be joined on stage by Mark Lawson.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHistory is at the core of Harris’s writing. The former political journalist made his name in fiction with Fatherland, his 1992 novel about an alternative history in which Nazi Germany won the Second World War. Other celebrated works include Pompeii, his Cicero trilogy and The Ghost, which is just one of his books adapted for screen.

What is it about history that he finds so compelling as a fiction writer? He tells The Yorkshire Post: “I think there's a great benefit in writing about the past, in that it enables you to write about the present without doing it head on. It doesn't date. If you write historical fiction, if you get it right, it’s still fresh years after you've written it. Whereas a contemporary novel could date very quickly. And it's just rich to reimagine the past and to walk down the street - (or) a journey, a meal - they all become more interesting because there's this exotic quality to them.”

However, there is a sense of responsibility when writing about real events.

“I think that the reader has to trust the author,” he says. “If I describe the execution of Charles I, I hope that they know that I will have researched it carefully and I will describe it as close as possible as to how it was, how it might have been observed by someone across the street. That is based on historical fact, research. And I try to get things right. If they're not right, then I can't believe them, and if I can't believe them, the reader won't believe them either. So I’m quite meticulous about that.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I never put anything in a novel that I know for sure didn't happen, (or) couldn't have happened. That's the line for me. After that, I think that it is a novel and I’m at liberty to invent a character, insert characters into historical record in various conversations and so on to illuminate whatever it is I'm trying to write about. But by and large, I always think that in a novel of mine, if something seems improbable, wild, fantastical, (then) it's true, and if it seems dull and plodding, it’s something I've made up.”

When it comes to research, Harris feels that it is important to go beyond reading historians to seek out speeches, letters, diaries and memoirs of those living in the period he is writing about.

The famous diaries of Samuel Pepys and the speeches of Cromwell himself provided some of the context this time.

Harris adds: “I must be about the only person who has bought, in the last few years, the seven volumes of (Oliver Cromwell's secretary) John Thurloe’s state papers. I mean, hundreds and hundreds of thousands of words. Most of it, of course, completely useless from my point of view, but the two regicides, Colonel Whalley and Colonel Goffe, both wrote to Thurloe, so it gives me some letters from them. And also, that's just the world - it's like swimming in the sea of the 17th century, to read all that material. The way people addressed one another, the intrigues, the use of codes and ciphers when they communicated - the whole society is sort of laid out in volumes like that.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Act of Oblivion title is a reference to a 1660 Parliamentary act which generally pardoned those who committed crimes during the English Civil War. Exceptions, however, included the men involved in the regicide of Charles I. Such a turn of events allowed Harris to write a procedural novel about the ensuing manhunt for those who conspired to kill the king. He was surprised that the Civil War period has not been written about as much as other eras.

“It is a very complicated story. It's a mixture of politics, economics and religion, and religion actually is probably the most important element. And it is quite hard for us to get inside that mindset of how people thought at that time. Religious belief and how you worshipped were absolutely central to how you lived your life. Cromwell said ‘we will cut off the king’s head with the crown upon it’, meaning it wasn't just getting rid of Charles I because they couldn’t trust him, they were getting rid of the institution of the monarchy all together, and the House of Lords and the bishops, so that there was no interference between the plain, simple meeting house Puritan worship and God. There was no state, there was no king or bishops between them. That is a very powerful idea, but it's not necessarily easy to grasp.”

During his visit to Yorkshire, Harris hopes to visit Haworth to see where the Brontë family lived.

He might make another stop, too, at the Battle of Marston Moor site in North Yorkshire. Fighting there on July 2, 1644, ended with the first major Royalist defeat in the English Civil Wars and the battle was reputedly one of the largest ever fought on English soil. “It was colossal, there were I think over 40,000 men engaged at that battle. Colonel Walley, the father in law in my novel, was the man whose cavalry pierced Prince Rupert's line and they broke the king's army, captured his correspondents and it was a turning point in the history of the war.”

Yorkshire, as ever, right in the thick of it.

For tickets, visit harrogateinternationalfestivals.com