Come and see the full Ponte

There’s a sign on the road leading into Pontefract. It says, simply, Home of Haribo. It was back in 1972 that Dunhills, manufacturer of the famous liquorice Pontefract Cakes, was bought out by the German confectionery giant and its presence is now hard to avoid. Ask directions to the town’s museum and most will tell you it’s near the Haribo outlet shop.

One of the area’s biggest employers, Haribo has brought much-needed jobs to this corner of West Yorkshire, but there are some who can’t help wishing that Pontefract was known for more than just its contribution to the gums and jellies market. One of them is Ian Downes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAn archaeologist by training, he’s now curator of Pontefract Castle and a walking encyclopedia when it comes to the town’s place in the history books. He’s not the only one. While the town has a population of less than 30,000, it boasts societies devoted to local archaeology, history and heritage and this year they are joining forces with the hope of using the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta – and Pontefract’s involvement in the birth of the historic document – to promote the town as a tourist destination.

“John de Lacy of Pontefract was one of a group of 25 barons who really pushed through the Magna Carta. The castle had been in the family since the 11th century and John De Lacy should have inherited the estate following the death of his father in 1213. However, King John quite fancied it for himself.

“Understandably, the De Lacys were a little annoyed and as opposition to the king began to grow they forced him to commit to the Magna Carta which basically enshrined a number of rights in law.”

The document effectively sought to limit the powers of the king, who had levied heavy taxes on his subjects to pay for a series of unsuccessful wars abroad and laid down the principle that ‘No free man shall be arrested, or imprisoned, or deprived of his property, or outlawed, or exiled or in any way destroyed, unless by legal judgement of his peers, or by the law of the land’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPerhaps predictably the uneasy peace didn’t last, but John de Lacy’s place in history was assured and now 800 years on Ian is trying to raise awareness of the role that the town played in shaping British politics.

It’s a big task. At the heart of historic Pontefract is the castle, but the medieval ruins are barely visibly from the road and the town isn’t as easy a sell to tourists as a York or Harrogate.

“The Victorians remodelled the castle grounds and planted a large number of saplings,” says Ian. “I am sure they looked lovely at the time, but trees grow and while you can just about spot the castle through the branches in the winter, in summer it’s completely obscured.

“When you’re in the grounds they do help to create quite an intimate atmosphere, so we don’t want to remove them all, but we have been working with English Heritage to see which ones could be taken out. We really just want to say to people: ‘We’re here, come have a look’.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe castle has recently secured £3.4m of Heritage Lottery Funding which will help realise ambitious plans for the landmark. Some of the money will be spent on essential maintenance of the castle ruins, while the rest will be invested into the kind of facilities that 21st century visitors expect from an attraction.

“The problem is that when the castle was built, no-one suspected it would stay up for this length of time,” says Ian. “Certainly no one thought people would be interested in walking round its ruins. When we started applying for funding we had to show what was possible. We put up new information signs to guide visitors around the ruins and from what we’ve learnt from staging the summer proms events, we know there is so much potential.”

The pinnacle of the four-year project will see a redundant barn, which over the years has been variously used as a boxing arena and blacksmiths, turned into a tearoom and the entrance to the castle, which has been on English Heritage’s At Risk Register, reorientated to replicate as closely as possible the pathways and gates of medieval times.

“This castle has so many stories to tell,” says Ian, unlocking the metal doors to the dungeons. “Originally it was built as a wine cellar, but during the English Civil War they made a convenient prison.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDescribed by Oliver Cromwell, leader of the Parliamentarians, as “one of the strongest inland garrisons in the kingdom”, the castle was a Royalist stronghold during the bitter conflict and some of those who found themselves imprisoned there left a lasting impression on the building’s stonework.

“There it is,” says Ian, pointing to the name John Grant etched into the stone, alongside the date, 1648. “A perfect example of Civil War graffiti. There wouldn’t have been a lot of light down here at all and to pass the time the prisoners took to scratching their names with belt buckles into the stone, which were illuminated by shafts of light.

“There’s all sorts of stories associated with the dungeons. Local legend has it that one particular stone is actually a doorway leading to a number of secret passageways.”

Disappointingly, Ian rebuffs the story – what looks like an opening, he says, is in fact just a natural fault in the rock. Similarly the red staining on much of the stone is not the blood of ancient prisoners, but iron in the rock itself and while many claim to have taken photographs in the dungeon displaying ghostly orbs, Ian is a man who clearly prefers to stick to the facts rather than indulge in fiction.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLeaving behind the relative warmth of the dungeon we head round the corner to the Gascoigne Tower which once housed Pontefract’s most infamous prisoner.

“Yep, this is where Richard II breathed his last,” says Ian, who worked for York Museums Trust before moving to West Yorkshire. “There are two versions of the story, one that he starved himself to death, the other that he was starved to death. It didn’t look good to murder a king, but starvation was seen as natural causes, so it absolved everyone involved of guilt.”

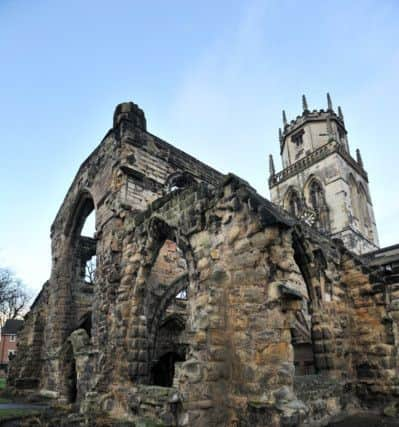

It’s not just the castle which made Pontefract historically important. Down the hill and across the road is All Saints Church where a new place of worship was built inside the ruins of the original Saxon building.

“During the Civil War, the church fell within the castle’s siege trenches and was used as a garrison for the troops,” says Ian. “We’ve been working with specialists from Huddersfield University on the impact of that conflict. The entire structure is pitted with holes, scars from the blasts which would have been fired from enemy troops stationed on the hill just across that road.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith the Lottery funding in place, Ian and the rest of the team now have something of a blank canvas and believe that Pontefract’s history deserves to be better known.

“Everywhere you turn in this town, there is something of historic importance,” he says. “Look over there to those fields, that was once the site of St John’s Priory which was torn down during the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

“A significant amount of excavation went on during the Victorian period, but the remains are better protected underneath the ground than they ever would be if they were exposed to the elements. You can’t see it now, but during the summer a group of volunteers mow the grass in such a way that it shows the outline of the original building.

“This town is brimming with history and the Magna Carta anniversary will hopefully give us a platform to raise awareness of these hidden gems.”

The Nelson Room

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBack in the mid-19th century, the MP for Pontefract, Benjamin Oliveria, happened to be a friend of the Irish sculptor John Edward Carew, best-known for his work Death of Nelson, one of four bronze panels which decorate the pedestal of Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square. Oliveria suggested to the town’s mayor that the original plaster casts would look good in the town. The mayor agreed and in December 1855 they arrived in Pontefract. Joy quickly turned to dismay when the bill for transportation and installation was received. The town reluctantly paid, but Oliveria’s name was deleted from the accompanying plaque.

The Buttercross

While it’s one of Pontefract’s most familiar landmarks, few know the history behind the Buttercross. It was erected as a memorial to Solomon Dupier who was a member of the Spanish garrison at Gibraltar in the early 18th century. Details are scant, but it is believed Dupier colluded with English forces when they launched a successful attack on the Rock in 1704 and afterwards moved to England, settling in Pontefract. Later the Buttercross was where farmers’ wives sold their wares and where at least one man sold his wife. In 1803, a newspaper reported that a Mr Smith brought his wife from Ferrybridge to Pontefract with the hope of auctioning her off. Bidding eventually finished at 11 shillings.

The Secret Ballot

The first secret ballot to elect a Member of Parliament was held in Pontefract. The by-election of August 1872 was triggered following the resignation of Hugh Culling Eardley Childers, who had entered the House of Commons in 1860. It was the first time that people had voted in secret by placing an X on a ballot paper next to the name of their choice and the original box is now on display in Pontefract Museum.

• For more details go to www.pontefractheritagegroup.co.uk