Up for debate in Leeds: The Future of books

THE death of the book as we know it has been predicted for years, decades even.

Cinema, radio and television have all been billed as the likely culprits at one time or another, and yet books have endured the slings and arrows of outrageous naysayers and remain alive and seemingly well.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYou might think by now people would have stopped trying to herald its demise but the digital revolution, which has transformed not only the way we read, but how we listen to music and watch films and TV, has brought it back into sharp focus.

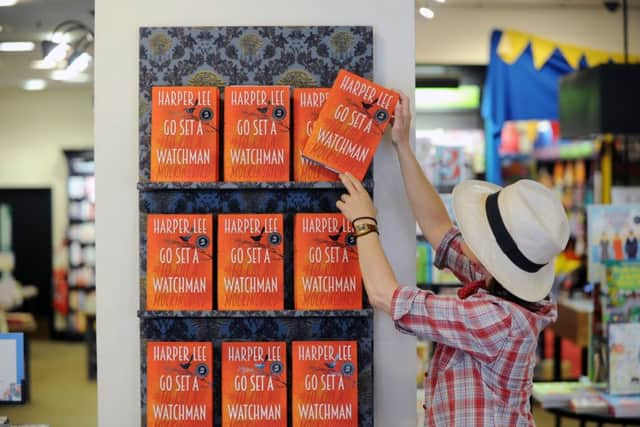

In the space of a decade the book publishing world has found itself in the grip of a global upheaval it hasn’t faced since the advent of the paperback in the 1930s. Giant publishers are merging to become even bigger in order to square up to new digital media giants.

But what does all this mean for the traditional book that we all know and love? It’s a question at the heart of a public debate being hosted by the University of Leeds this week – the centrepiece of a programme of events organised by the White Rose University Consortium.

Melvyn Bragg, the University of Leeds’s chancellor, hosts The Future of the Book – which will examine the place of books in the digital age. Among the other guest speakers are Linda Grant, the Orange Prize-winning author who wrote about getting rid of her books in I Murdered My Library, and experts from the universities of York, Sheffield and Leeds, which make up the White Rose consortium.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is part of a wider Debating the Book programme running throughout this month, featuring talks, exhibitions and guided reading groups.

Professor Gregory Radick, Director of Leeds Humanities Research Institute, who organised the event, says books are part of our history. “For centuries, the bound volume held an esteemed and seemingly invincible place in our culture. But in the digital age, nothing about the status of books – or even their survival as physical objects – is certain.

“How should we understand where we are now, somewhere between the old print culture and the new digital one? What lessons does the past hold when it comes to today’s concerns? Does digitisation herald the end of the book or a new beginning … or neither?”

Novelist Linda Grant is among the panel discussing this topic. She believes the novelty of e-books has started to wear off. “My understanding is that the decline of paper books has now stopped, I think people are going back to paper books but at the same time they aren’t rejecting e-books.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut while the decline in sales of paper books has settled down, the pressure on independent bookshops from online retailers shows no sign of abating. “The whole nature of browsing has changed because local, independent bookshops just aren’t there any more,” she says.

“My local bookshop closed down about four years ago and they told me it was because people were using Amazon. They would come in and do a bit of browsing, note down the ISBN and go and order the book online. What kept them afloat for a while were the Harry Potter books, but once they stopped they were finished.”

It’s not the only thing that concerns Grant. “Young people hold the key and the worrying thing is that there are lots of young people who aren’t reading books. There’s plenty of other things to keep them occupied like gaming, Instagram and Snapchat and they’re spending more time on their smart phones and ipads.

“The generation that grew up in the pre-digital age will keep on reading, but the generation after that? I honestly don’t know.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Another question encompassed in the future is what kind of books are there going to be, and if they do exist mainly on digital platforms will they become a more interactive medium? If you look at it in a more apocalyptic way, will anybody want to pay for a book, or will it be like music with digital downloads?”

James Daunt, managing director of Waterstones, is another of the speakers at Thursday’s event. Daunt is the man credited with transforming the company, which has seen book sales rise during the past two years. He believes the paper book still has life in it. “A year or two ago one would have had one’s fingers slightly crossed,” he says.

But he also feels that e-books have their limitations. “They have their place, but they aren’t a substitute for a physical book, you don’t remember what you read in the same way,” he says. “The digital experience is different from the physical one – you can’t bequeath a digital book to your children or grandchildren.”

Nevertheless, the emergence of e-readers and Kindles has forced publishers to up their game by making books more enticing. The same goes for booksellers who have had to adapt or risk going to the wall. “Bookshops are social spaces now, they’re not just about selling books. They have to look and feel interesting.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut while Daunt believes bookshops and publishers can survive the rise of e-books, he is less optimistic about the future of reading itself. “The much greater threat is whether people continue to read because there are so many other things competing for our leisure time.”

This, he believes, is something that needs to be addressed. “How do we get people to reconnect with books, and particularly the physical book? That’s the challenge not just for booksellers but also for authors and publishers.”

Melvyn Bragg, whose new historical novel Now is the Time – set during the 14th century Peasants’ Revolt – is published this week, believes it’s an important debate. “I’ve a vested interest in the future of the printed book, but I’m also intrigued by the changing ways in which readers now choose to enjoy the printed word,” he says.

So how serious are the challenges facing the traditional book? “They are quite serious but I don’t think they’re fatal,” he says. “When cinema came along people said that the theatre would be finished. Well, today the theatre is thriving as never before and so is cinema. They said the same thing about radio and TV and they’re both still here.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn other words they can happily co-exist with each other. But that’s not to say the future of paper books is necessarily secure. “Bookshops are closing and public libraries are under pressure which means there are fewer places to get books,” he says.

Nevertheless, Bragg doesn’t believe traditional books are facing their last hurrah just yet. “There may be a short term impact but in the long term they will recover. If you look at theatre and radio they’re still here and they have come roaring back.”

The Future of the Book is a free event held at the university’s Great Hall on Thursday from 6pm - 7.30pm. For more details call 0113 343 39809.