Jayne Dowle: What I've learned about war, sacrifice and remembrance since I made the mistake of shunning the red poppy

Just before I put the vegetables on for dinner, I wandered into the living room to see if the dog was OK. The poor thing was distressed by fireworks going off left, right and centre, so we put the television on to muffle the noise.

There is only so much stimulation I can bear at that time on a Sunday, so we went for The Antiques Roadshow. Fiona Bruce was making her introductions from a war cemetery in northern France. This looked more interesting than the usual queue of individuals pretending to be nonplussed at the prospect of that ugly painting from a jumble sale turning out to be a Van Gogh.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

My partner, Simon, beckoned me to sit down. The vegetables could wait a minute. Actually, the vegetables ended up neglected for the next hour or so until both of us had recovered our composure enough to deal with the carrots.

Ms Bruce set out her stall. There were to be no valuations today. Just remembrance. I’d like you to think about that word ‘remembrance’ for a moment. Until this year, which marks the centenary of the end of the conflict, the word ‘remembrance’ has always evoked, certainly for me, militaristic glory.

Drums, pipes, marching bands and a kind of empty feeling inside, I struggled to connect because all my ancestors in this war were on the home front, down the pit or in the mills.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs a politically-idealistic teenager reared on Wilfred Owen, I shunned wearing a red poppy, choosing a white one for peace instead. I railed against celebrating the fact that so many had sacrificed so much.

I’ve learned a lot since then, but I don’t think I’ve ever learned as much as I have in the last couple of years. And that’s because through the modern urgency to feel everything, to bring long-buried memories alive, out of the attic and off the page, the media, film and television has made so many personal stories come alive.

This helps us to talk and discuss and come to our own personal terms with the reverberations. One rainy afternoon over half-term, I persuaded my 13-year-old daughter, Lizzie, to watch the film of Vera Brittain’s A Testament of Youth, an account of her life during the First World War. The novelist was a nurse on the Western Front and lost her fiancée, her brother and many friends, all under the age of 25.

Afterwards, Lizzie and I talked quietly about how we would cope if her brother volunteered or was conscripted. We also considered whether we would be brave enough to follow him. And we thought about our respective grandmothers who both served in the ATS (Auxiliary Territorial Service) during the Second World War, they were a cook and a secretary to anti-aircraft officers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

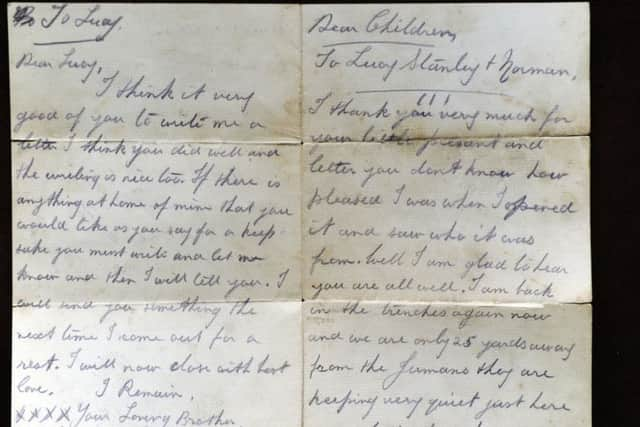

Hide AdConnections through the generations. That’s what true remembrance is. And through the fragment of a letter, a photograph of a handsome young man so full of promise mown down in the mud, a tarnished engagement ring or a helmet with a bullet hole, that edition of The Antiques Roadshow made them too.

It made us think about ourselves – what would we have done in the war, how we would have expressed our love and regret, how we might feel to lose a fiancée, a husband, father, child. This is where remembrance becomes personalised. It gains the power to move us to our core because we engage with it directly. We learn names, we read handwriting, we recognise both courage and fear.

This process lies also at the heart of Jeremy Paxman’s four-part series Britain’s Great War. I’ve not seen it all yet, but the programme I have watched talked about British politicians on the verge of war breaking down in tears and even resigning their posts at the prospect of the hell they were about to unleash.

I’m looking forward to seeing the one where he explores the bitterness of striking Glasgow shipbuilders who felt that it was not their war but a fight belonging to their bosses.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor only now, a hundred years after the war ended, are we publicly coming to terms with the other side of sheer courage and blind hope. Paxman’s series also examines how when the flood of volunteers became a trickle, and conscription was introduced, more than a million men appealed against going to war in tribunals held in every town in the country.

I didn’t even know these tribunals existed until the other week when I picked up a copy of a commemorative community newspaper in the South Yorkshire farming community of Penistone. Here I found a string of accounts of employers and workers begging to be excused from military duty because they were needed on the land.

Less than a generation ago, we would have found this distasteful, a sign of weakness, embarrassing even. Now we know better; those who gave their lives, who made difficult decisions which would haunt them forever, were human after all.