Nostalgia on Tuesday: Hall of fame

John’s ancestors had accrued wealth over the previous two centuries and his father, Henry, acquired the Oakwell manor that comprised a small farming community during the 1560s, along with other areas of land in Heckmondwike, Heaton and Gomersal.

Using contemporary architectural features, the present Oakwell Hall stood proudly in the landscape underlining the Batt family’s standing among the area’s prominent gentry.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

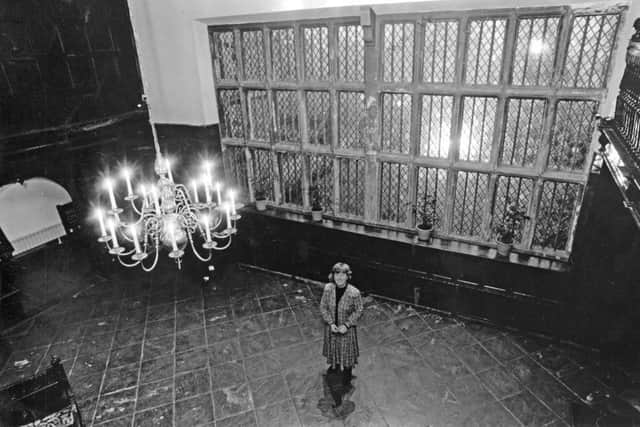

Hide AdOakwell Hall comprises a central hall flanked with cross wings at either end. An entrance porch, adjacent to the east wing, gives access immediately to a passage stretching through the house.

John Batt’s sons were well educated and attended university. Robert Batt inherited the hall in 1607 but did not live there, leasing it to his cousins, the Waterhouse family. Robert was succeeded by his son John. He, allegedly, led an adventurous and colourful life.

Among the changes to the house during the 17th century was the switch of the hearth position in the hall. Originally a fireplace backed on to the passage; it was moved to the hall’s north wall. The large hall’s mullioned transom window replaced two smaller windows and a new window was inserted above the entrance. The early 17th century may have been the period for the construction of the north-west wing in an effort to provide more service rooms.

John Batt became a captain in Sir William Savile’s regiment which took the side of the Royalists in the Civil War. After the hostilities, because of his Royalist allegiance, John was fined a tenth of his estate’s value, amounting to £360.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn emigrated to America during the 1640s to seek his fortune with three of his sons. In collusion with Sir Thomas Danby, of Farnley, he organised the transportation of settlers but the two men quarrelled. Two of his brothers did, however, settle quite successfully in Virginia.

Following John’s death in 1652, his son William took control of the family estates but decided to live at Howroyd Hall – his wife’s family home. His son, also called William, was his successor and died a strange death which has provided the hall with a ghost story. This alleges, on the day he was killed in a London duel, his ghost returned home, walked through the Great Hall, past his astonished family, continued upstairs and into his bedroom. Not only did he disappear, he left a bloody footprint in the doorway.

The Oakwell estate continued to thread its way through various members of the Batt family until a break occurred in 1747 and parts of the estate were sold.

A lawyer, Benjamin Fearnley, bought Oakwell but his son, Fairfax, too burdened with debts, sold it during 1789. Afterwards the house was leased to a number of schools and families. Those who ran boys’ and girls’ schools there included Henry Millard and the Carter sisters. A notable tenant was George Maggs, a Batley solicitor.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen the building housed a girls’ school run by Hannah Cockhill and her daughter, they were visited by Charlotte Brontë (1816-1855). She took inspiration from the house to include it as ‘Fieldhead’ in her classic novel Shirley, the home of her heroine.

The Leeds Mercury of April 20, 1926, reported that an attempt to save Oakwell Hall with its Brontë associations from being dismantled for the benefit of American or other foreign purchasers was decided on at a conference at Birstall Council offices. A decision to accept an option on the purchase for £3,000 of Oakwell Hall was made by the committee representing architectural and scientific interests in the West Riding on February 18, 1927.

The sub-committee appointed to interview Messrs Newsam & Gott, agents for the owners of the hall, the Hon EA Fitzroy and Mr Wheeler, reported that the owners were prepared to sell the hall as it stood, with gardens, paddock, and moat, for £3,000 including an option of purchase and giving reasonable time in which to raise the money. The owners themselves each promised to contribute £250 to any fund which was raised for that object. The meeting decided to accept the offer of the option.

By May 1928 the donors were also financing, at their own cost, the restoration of the hall, its gardens and grounds as nearly as possible to their original state. The cost was almost as much as the purchase price of the hall (£2,500).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMany years earlier, the oak panelling of the well-known drawing room was painted in a shade of pinky-white. Charlotte Brontë saw it, and liked it, for she wrote in Shirley: “I cannot but secretly applaud the benevolent barbarian who had painted another and larger apartment of Fieldhead – the drawing room to wit – formerly also an oak room – of a delicately pinky white.”

Initially, when opened as a museum, Oakwell Hall disappointed the public. One disenchanted visitor wrote: “...a scene of almost indescribable solitude and coldness...A bare stone floor, signs of decay and need for renovation, and a balcony that one could imagine might fall at any moment’.

Gradually, Oakwell Hall acquired more objects, appeals were launched and some significant loans were obtained from the Victoria and Albert Museum. Displays depicted a range of periods but from the mid-1980s, following a detailed research project, the permanent displays were organised for the hall to reflect the Batt family home of the 1690s.