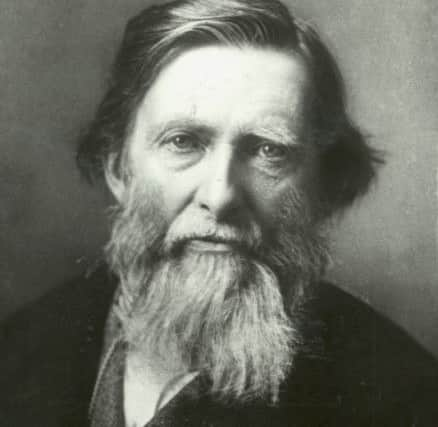

Portrait of an idealist

Only the name on the gatepost offers a clue about what used to go on here. “Ruskin House” it says in bold, no-nonsense letters. Though now much extended, converted into flats and hemmed in by other houses, the building has a hallowed place in Sheffield history.

Up on a steep hillside in the suburb of Walkley, Ruskin House was once St George’s Museum, a small, sturdy villa housing the amazing collection of pictures, manuscripts, books and minerals built up by John Ruskin, the Victorian writer, artist and social campaigner.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRuskin’s Sheffield legacy is being celebrated this year in an ambitious community heritage project that will take in, among much else, walks, talks, an archaeological dig, a little-known early 20th century artists’ colony based at a corn mill, exhibitions, a cabaret, workshops in harvesting and hand-forging, a “pop-up community museum”, tool-making, bread baking, and the life of a boomerang enthusiast. And if all that sounds rather quirkily wide-ranging – well, Ruskin was.

“He was asking how we can have happier, more sustainable lives,” says Ruth Nutter, producer of the Ruskin-in-Sheffield project, which is backed by £67,000 from the Heritage Lottery Fund. “His collection was about making connections between art, nature, architecture, well-being and wealth.”

The collection is now housed in the city’s Millennium Galleries, but it started out in 1875 at St George’s. It came to Sheffield partly because Ruskin, whose radical ideas influenced Gandhi, Tolstoy and the Labour Party, admired the skill of the city’s cutlery and tool-making craftsmen.

He was dismayed, however, by the impoverished conditions – social and educational – in which they lived. “The city had some of the worst slum conditions in the country,” says Ruth Nutter. “He thought that to be a good craftsman you needed a close relationship with nature. So it was quite rich political ground.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRuskin, famed in later life for his luxuriant waistcoat-sized beard, saw the craftsmen as victims of capitalism. “It is not that men are ill-fed,” he wrote, “but that they have no pleasure in the work by which they make their bread, and therefore look to wealth as the only means of pleasure... they feel that the kind of labour to which they are condemned is verily a degrading one, and makes them less than men.”

So, in a fine spirit of idealism, he tried to improve the quality of their lives by making them aware of a cultural world beyond their workshops, to create awareness of some of the wonders of civilisation. “There is,” he said, “no wealth but life” and he set out to provide things to stimulate “a man who has only a quarter of an hour to spare a week”.

His collection, financed by his inherited personal fortune, was crammed into the museum’s single 13ft square room. It was so cluttered that a newspaper reported it “held about two people with comfort but no more”. It was visited by Prince Leopold, Queen Victoria’s youngest son, the artist and designer William Morris, and, probably more importantly, thousands of Sheffield workers and their families.

Over the years, the museum was extended before moving in 1890 to bigger premises across the city in Meersbrook Park, where it attracted more than 60,000 visitors a year from all over Britain, the continent and the Far East. By the 1950s, however, Ruskin’s ideas had fallen out of favour, he gradually slipped from the collective Sheffield memory, and much of his collection was put into store in Reading.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt returned to Sheffield in 1981 and a new – and for many people enchanting and enriching – Ruskin Gallery opened in the city centre four years later. One newspaper reviewer reckoned it sat “like a new-minted jewel amidst the urban clutter of Brutalism”.

Its first keeper was Dr Janet Barnes, now chief executive of York Museums Trust and a director of the Guild of St George, the educational charity which owns the collection and promotes Ruskin’s ideas.

“If you look at the reasons other philanthropists gave collections, it was because they reflected their status and wealth, but Ruskin’s was in a completely different arena,” she says. “My first reaction when I saw the collection was: ‘What’s the connection between these minerals and bird prints and manuscripts? What’s the key to it all?’.”

The key, she decided, was “looking carefully and being mindful of what you’re seeing” – reflecting Ruskin’s belief that “You can no more see 20 things worth seeing in an hour, than you can read 20 books worth reading in a day. Give little, but that little good and beautiful, and explain it thoroughly.... The less you have to look at, the better you attend.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThat philosophy continues today at the Millennium Gallery, which has housed the collection since 2001. Only a fraction of it is on show at any one time, but a central exhibit is a huge canvas, from around 1880, of St Mark’s Basilica in Venice.

Its artist, John Wharlton Bunney, spent 570 early morning sessions creating it to inspire people who could never hope to see St Mark’s for themselves: these were the days before affordable package tours.

The collection’s delights are generally on a much smaller scale than Bunney’s picture, however. There are copies of Old Masters and plaster casts of Renaissance sculptures (mostly commissioned by Ruskin), detailed architectural studies and drawings of flowers, insects and leaves, and Ruskin’s own painstaking watercolour of a peacock’s feather. There are medieval Books of Hours, their margins alive with strange beasts, and displays of minerals – quartz, agate, amethyst – with the sign “Please feel free to touch.”

A soundtrack of birdsong and running water plays almost imperceptibly in the background. Ruskin admired the countryside around Sheffield, the fact that you could see the hills from the city centre. The East End may have been polluted but the horizon always promised fresh air.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRuskin-in-Sheffield will celebrate this rural side of his vision with events inspired by St George’s Farm in Totley, on the Peak District border, which he set up to support a co-operative community. They could grow their own food, make a living from their craft skills, and generally reconnect with the countryside. The events include a community performance led by the Totley-based poet and songwriter Sally Goldsmith. The project, says Ruth Nutter, will aim “to reach a wide audience and get people to reconnect with Ruskin, to engage with him on all levels – creative, practical, hands-on, not just scholarly.”

It will explore some of the first curators of St George’s Museum, notably the very first, Henry Swan: engraver, photographer, vegetarian, Quaker, Spiritualist, pioneer bicyclist and enthusiast for boomerang-throwing as exercise (it didn’t catch on).

The collection made a deep impact on many visitors. Benjamin Creswick, for instance, lived a few yards from the museum and worked as a knife-grinder. After becoming a protege of Ruskin, he went on to be a successful sculptor, exhibiting at London’s Royal Academy.

He put his earlier career to good use, however, for his terracotta frieze for the front of the Cutlers’ Hall in the City of London. It shows muscular craftsmen in cramped workshops making knives and scissors. Creswick gives them real dignity.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo is Ruskin still relevant? “Incredibly relevant,” say Ruth Nutter, and goes on to quote him: “The measure of any great civilisation is its cities, and a measure of a city’s greatness is to be found in the quality of its public spaces, its parks and squares.” A 21st century environmentalist could hardly have put it better.

“Yes, the abiding thing about Ruskin is that he’s always relevant,” says Janet Barnes, author of an absorbing book about his Sheffield associations. “He was a free spirit, with a very original outlook, which he described from his own experience, so you can have that experience yourself.”

But, if he’s always relevant, is he always right? “That’s difficult,” she says. “I wouldn’t say he was always right; he contradicted himself all the time. But no-one would argue about the value of opening people up to a broader range of experience.” She adds that he appealed to Sheffielders’ radical, independent spirit, and that the project is “as much about Sheffield as it’s about Ruskin.”

Ruskin remains a contradictory figure. Asked which political party he would support today, one admirer reckons he would be “Labour or Green – but mostly Green”. Another, however, sees him as “an old Tory, a rich boy... sometimes accused of being patronising”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere is, after all, a story about a man who tugged eagerly at Ruskin’s sleeve after a lecture and said how much he’d enjoyed reading his books. “I don’t care whether you enjoyed them,” said Ruskin. “Did they do you any good?”

• For more information visit www.ruskininsheffield.com

Millennium Gallery (0114 278 2600, www.museums-sheffield.org.uk).

Ruskin in Sheffield by Janet Barnes, is published by Museums Sheffield in association with the Guild of St George, available at the gallery, priced £6, and online.