A ramble back in time

On the right day the village of Hubberholme says all that needs to be said about the Yorkshire Dales: a pub, a church, a bridge over the infant River Wharfe, a timeless backdrop of blue skies and rolling hills.

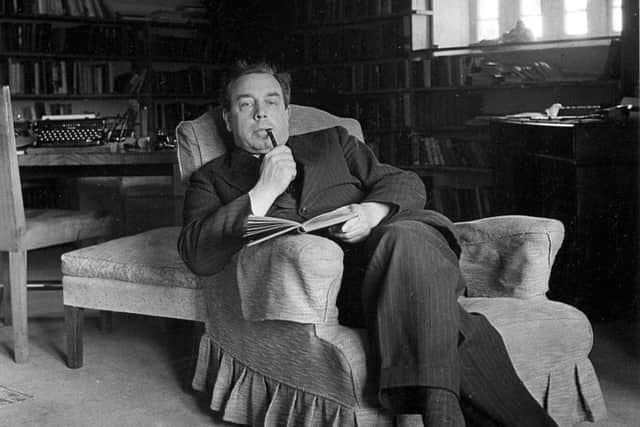

JB Priestley described it as “one of the smallest and pleasantest places in the world” – and he was well qualified to judge. Between the wars he travelled to all four corners of the country to research English Journey, his classic account of society in change.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe is known to have drunk in the local pub, the George Inn, and to have recharged his batteries in the surrounding countryside after military service. It came as no surprise that his ashes were scattered in the village after his death in 1984.

Today, a plaque in the Church of St Michael and All Angels is the most visible reminder of Priestley’s connection to the village. It comes at roughly the halfway point on a walk which, we hope, explains why this corner of the Dales was remembered with such affection by the writer.

I’ve walked this circular route from Buckden to Hubberholme and back along the bank of the Wharfe ever since I was a schoolboy in Leeds. Its main appeal lies in the contrast of spectacular views down the valley (there’s a section of limestone pavement above Cray which I reckon is one the best spots in Yorkshire to enjoy “elevenses”), riverside scenery and traditional Dales architecture.

But when Diane Roberts and I came to research our book Walking the Literary Landscape, a guide to 20 walks with literary connections in northern England, it was the area’s links to Priestley that were irresistible.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere are six Yorkshire walks in the book, reflecting the county’s contribution to literature as much as its natural beauty, and exploring the intriguing relationship between the writer and his or her surroundings.

The novels of the Brontë sisters are of course famously soaked in the moorland landscape around Haworth. Our walk to Top Withens takes the admirer to the heart of the sisters’ fascination with place (and may expose the unwary to the realities of a “wuthering” climate).

Victorian writer Charles Kingsley’s links to Yorkshire are also well documented. The Water Babies, his most famous novel, is clearly rooted in the splendid walking country around Malham and includes a hair-raising descent of a fictional Malham Cove by its chimney-sweep hero, Tom. Kingsley stayed at Tarn House, now a field centre, during his time in Malham.

But what was it about Whitby that immediately struck a visitor called Bram Stoker as the perfect setting for his Gothic tale Dracula? And why, long after moving away, did Ted Hughes return time and again in his poetry to the Calder Valley he knew as a child?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSometimes the connection was a physical one with the act of walking. William Wordsworth is said to have walked 175,000 miles in his lifetime, revising lines of poetry on the move, and climbing Helvellyn much as you and I might pop down to the Spar shop.

Nor was he the only writer for whom walking was a necessary spur to creativity. Charles Dickens would think nothing of walking 30 miles at a stretch – often at night. Some of Dickens’s most famous descriptions of London and its inhabitants were said to have their origin in his nocturnal wanderings round the streets of the capital.

It is less well known that he and literary soulmate Wilkie Collins (author of the first English detective novel) ventured on a walking expedition to Cumberland in 1857 and, on the recommendation of locals, climbed Carrock Fell, north east of Keswick.

It was an ill-fated outing, recorded in comic detail in their subsequent account, The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices, and ended with the two of them soaked to the skin and Collins, a reluctant rambler from the outset, being helped off the fell with a sprained ankle.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThat description is also remarkable for the glimpse it gives us of what walking for pleasure was like more in this country than 150 years ago. We do know that Dickens and Collins had come reasonably well prepared – Collins in a brand-new shooting jacket he had bought in London, Dickens carrying a compass in a “smart red morocco-case” that unfortunately was broken as they stumbled about in the mist.

But the contrast with today’s walker in his or her breathable waterproofs and Gore Tex boots, and equipped with GPS tracker and obligatory high energy bar, could hardly be greater.

Dickens was a master of the telling detail, the physical quirk or verbal tic that distinguished one of his army of minor characters from another. In the course of writing and researching our book we came across a few of our own.

Which takes me back to Hubberholme and a fairly notorious (former) landlord of the George Inn. We had called in there with friends from Lancashire to get a sense of why, of all the places he must have visited, of all the pubs he must have drunk in, Priestley considered Hubberholme, and the George, paramount.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMy friend, a cricketer of some talent in his younger days, breezed up to the bar and said he didn’t suppose the landlord would happen to know the Test score, would he? The landlord fixed him with a withering eye and replied: “Ay, you’re dead right lad – I wouldn’t!”

For my friend, of course, this was enough to confirm his worst suspicions about Yorkshire landlords. But it struck me that Priestley, perhaps the original grumpy old man, would have fitted in perfectly. It was his spiritual home.

Walking the Literary Landscape, 20 Classic Walks for Book-Lovers in Northern England, by Ian Hamilton and Diane Roberts, is published by Vertebrate, priced £12.95. Follow Ian and Diane on Twitter @literarywalks