25 years of the West Yorkshire Playhouse

WHEN the the curtain went up on the long-awaited West Yorkshire Playhouse on March 8, 1990, it was accompanied by a great chorus of excitement.

Former Pudsey schoolgirl Diana Rigg was on hand to add a touch of glamour to the opening night celebrations, while Jude Kelly – the artistic director at the time – spoke of reaching out to different people across West Yorkshire irrespective of their age, background or ethnicity. The new Playhouse, she proclaimed, had a duty to be “the lifeblood of future theatre.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDubbed by some the “North’s new national theatre”, this £13m building at Quarry Hill in Leeds was a big deal not only for the city, but all those involved in the arts in Yorkshire. It had been six years in the planning and building and was the largest in the country outside of London.

The fact that it had actually come to fruition and in doing so silenced those critics who said it would never get off the drawing board, was important.

But despite all the hype surrounding its grand opening, not everyone was quite so enthusiastic. Particularly when it came to its appearance. Even the building’s most ardent fans had to admit the so-called ‘knitting pattern’ brickwork was no match for the splendour of somewhere like the Alhambra in Bradford, or the Leeds Grand.

The idea of the new Playhouse was that it was modern, classless and accessible and as one critic observed at the time: “Not for nothing does the exterior resemble a cross between a sports centre and a continental hypermarket.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut just as we’re told not to judge a book by its cover, so we shouldn’t dismiss a theatre because of its outward appearance – it’s what happens inside that counts.

The first production at the new venue was John O’Keeffe’s Wild Oats starring Reece Dinsdale, who recently returned there in Alan Bennett’s autobiographical play Untold Stories.

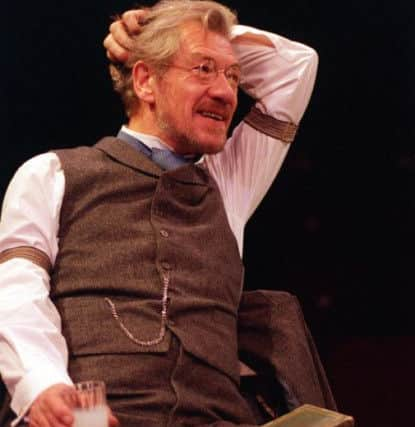

Since that first performance more than 322 productions have been staged at the Playhouse and many famous actors, writers and directors have passed through its doors including Sir Ian McKellen, Patrick Stewart, Prunella Scales, Sheila Hancock, Tim Pigott-Smith and Alan Bennett.

The theatre has played host to numerous critically acclaimed productions over the past quarter of a century, including the 2002 production of Hamlet, starring Christopher Ecclestone, and Northern Broadsides’ production of Othello with Lenny Henry in the title role.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis weekend marks the Playhouse’s 25th birthday and artistic director James Brining believes it continues to follow its ethos of theatre for all.

The Quarry Hill building replaced the Leeds Playhouse, housed at Leeds University, which many people had great affection for. “The old building is still there. I actually went there as a kid and I remember it being quite dark and intense.”

Brining, who grew up in the city, says one of the reasons behind the move to Quarry Hill was to make the theatre more accessible.

“I think moving here was a key thing for this theatre,” he says. “The shift from the ivory tower, if you like, down to the site of what was the biggest social housing development in Europe, is quite an interesting story.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo, too, is the story behind the area of land that once housed the notorious Quarry Hill flats. “There wasn’t a quarry here it was called Quarry Hill because it was the quarantine area of the city, the place that people were sent to outside the city walls back in Medieval times.”

Building a new theatre here was seen as a chance to revitalise what was a run-down part of the city. “We’ve always been about making great theatre but we’ve also been characterised by our engagement with local communities, and I think we are genuinely the people’s theatre of this city.”

Brining, who took over the artistic reins two-and-a-half years ago, remembers coming to the theatre in its early days and being impressed by what was on offer. “I remember the McKellen ensemble season, I remember seeing Singing In the Rain, and some of Matthew Warcus’s productions which were truly fantastic. But I also remember seeing tiny, little shows out in schools and communities.”

When the theatre first opened much was made of the fact that it had the 750-seater Quarry Theatre and the smaller studio-like Courtyard – giving it two theatres for the price of one.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBrining says part of the Playhouse’s success has been the variety of what it has to offer audiences. From popular, large scale productions to more leftfield work, like Shockheaded Peter which started here during the 1990s before going on to enjoy a run in the West End.

“We can’t just exist to satisfy theatre-lovers, we need to satisfy them as well as people who want to have a night out and watch a great show, or a family who come every Christmas, and people interested in cutting-edge stuff.”

Brining says that part of its remit has been to engage with as many parts of the local community as possible and points to the success of ‘Heydays’ – a creative scheme for the over 55s. “This started when the building first opened and we think it’s the longest-running arts programme for older people in the world. It’s incredibly popular and they do anything from singing and drama, to crafts and dance.”

The Playhouse has also reached out to those suffering from dementia. “We did the first dementia-friendly performance in a theatre that we know of, certainly in Britain, with White Christmas. We modified the performance so that people living with dementia and their families could come and enjoy the performance.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s something he feels sets the theatre apart. “This building is full of people all the time and it’s full of people who are very different from one another.

“We work with those who have learning difficulties, we work with people from areas of the city and the region that are disadvantaged, we work with asylum seekers and refugees, we’ve worked with people in their 80s with dementia and young children.”

But while few would question the positive impact the theatre has had on local communities, most would agree that after a quarter of a century it is due a refurbishment and possibly even a redesign. It’s something that Brining is talking to the Arts Council and the city council about. “There are certain aspects that need to be addressed from a physical point of view,” he says. “It’s not necessarily the most beautiful theatre in the world from the outside and it’s not how we would build this theatre if we were starting again. But you can’t just change a theatre because you want it to look different, there have to be bigger reasons than that and there are.”

He says the seating, lighting, air conditioning and disabled access need attention, as well as making the building more environmentally-friendly.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Having an entrance on the ground floor right opposite what will be John Lewis instead of having to come right up the stairs to go round the back and come in through what is effectively the back door, would make a big difference.”

But as well as the practical issues it’s also about the building’s aesthetics.

“The message I want to send out is ‘we are here, we are part of this city, part of this region. We are a place where exciting things happen, where glamorous things happen and also where you can feel welcome.’ I think that’s the balance that was trying to be struck when this building was designed, because there’s a danger with those beautiful lyric theatres that you go into them and you feel as though you’re going into a church.

“We’re not a church and we don’t want to be one. We want people to be going by on the bus thinking ‘that looks exciting, what’s happening there?’ Not ‘is that a swimming pool, or a supermarket.’ We want to be a beacon that helps illuminate the city.”