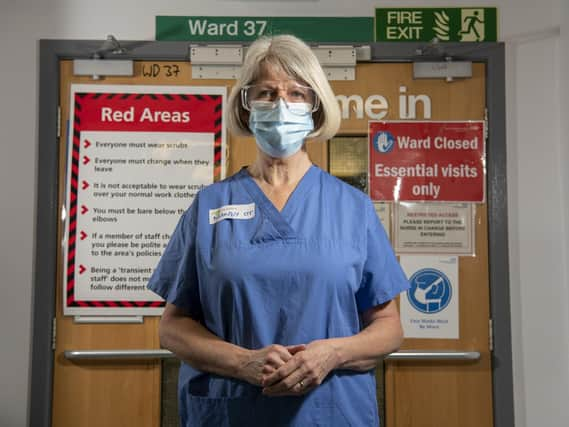

Inside a Covid ward - how staff at one Yorkshire Hospital are coping under unrelenting pressure

For everyone working on the frontline in the region’s hospitals, the last year has been the most difficult of their careers.

The unrelenting pace, the pressure of saving lives and the sheer number of deaths they have witnessed has left many NHS staff on the brink -- and the fight is far from over.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt York Hospital, the start of 2021 has been as brutal as the first wave. The city began the year with the highest rate of Covid-19 in the region, leaving wards filled with Covid patients alongside the usual seasonal illnesses.

Dr Joe Carter, clinical lead for critical care at the hospital, said a meeting was held in the city last February after the first UK Covid case, and health leaders scrambled to respond to the new threat without knowing what the year would bring.

He said: “The provision of a new workforce to deal with the extra patients has been an enormous challenge. There aren’t ICU nurses just sitting around waiting to be called in in case there’s a pandemic. They’re highly trained specialist members of staff who don’t appear overnight or grow on trees, so that’s always been a huge challenge for us.”

The arrival of the Nightingale Hospital in Harrogate nine months ago brought no relief to senior doctors because it was clear there would not be enough ICU nurses to run it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“When all the intensive care units in the country are already stressed and don’t have staff to run their own units, that was always going to be a massive, massive problem,” he said.

Nurse James Bennett is manager of Ward 29 at the hospital, which was previously an elective orthopaedic surgical ward, looking after people recovering from hip or knee replacements. But at the start of the pandemic he found himself suddenly managing a Covid ward.

He said: “We were just told one day that we were going to be a Covid-19 ward, which some of us took in our stride and a lot of people were very anxious about, as you would be, since it was a very unknown quantity.

“It was a very steep learning curve. Nobody knew what we were dealing with, it was just learning on a day to day basis.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTreatments have improved dramatically as medics have learned that steroids and some anti-inflammatory drugs can help keep people alive while they fight the virus but it is still very unpredictable.

He said: “We've had 104-year-old patients who've come in and spent a couple of weeks in hospital and gone home and then you have young people, 30 years plus, that become really poorly and have to go to intensive care.”

In York, treatments like continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) which would have previously been delivered in the intensive care unit (ICU), are being facilitated on other wards and a parallel ICU has been set up for non-Covid patients.

Dr Carter said: “We wouldn’t have the capacity to admit everyone that goes on to CPAP, which is what we think the prime minister had. We wouldn’t have the capacity to deliver all of that in the intensive care unit.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe ICU is only for the patients who are the most critically ill and they typically spend weeks or months there. It is so serious that anyone who has spent time in intensive care will never regain the level of health they had before they were unwell.

“The reality of intensive care is that it takes in the region of a year to get to the level of function that you’re going to get to, and that level of function is never the same as before you got ill. How much less is variable but you’re never as good,” he said.

Tasmin Putt is one of the hospital’s physiotherapists treating Covid patients on the front line in a very hands-on role.

She said: “We get called in overnight to help with acutely unwell patients who are in respiratory distress. So obviously that involves going into ICU and to see very poorly patients out of hours and at the weekend.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We go in to help patients maintain their airways, help keep their chest clear and help with oxygen therapy. They say that we're the only people in the hospital encouraging Covid patients to cough.”

Alongside this emergency work, Ms Putt, and her colleague Mandy Goodman, an occupational therapist, are primarily responsible for getting patients well enough to leave hospital and free up beds for new patients coming in. But this can be a long process, which often takes months and even just getting patients to the point where they can video call relatives is a huge achievement.

Ms Goodman said: “I don't really think people fully understand what we do, and the fact that we have extremely close contact with all these patients.

“Patients are very poorly, generally, they're very, very fatigued. And they take a lot of encouragement and time to encourage them to sit on the edge of the bed when they're very poorly. That can take so long, and then they're just too tired to do anything else.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBoth women have been at the bedside of dying patients, a traumatic experience for all staff, no matter how well-trained or experienced they are.

Ms Putt said: “Holding the hand of someone as they die and you being a stranger and not a loved one, that’s very challenging.

“It definitely takes a huge emotional toll on us. It’s extremely upsetting watching people die on their own.”

Having got into healthcare to help people, both feel a responsibility to keep going whatever happens.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMs Putt said: “We’ve been at 100% for so long and there is no break. It's just you keep going and you keep going.

“I'm sure that my partner has definitely been worried about me on some occasions, because it's physically demanding and it's emotionally demanding and you have to pull through so that you can go in the next day.

“It's really hard to kind of get it over in words.”

Public support has dwindled as the pandemic has gone on, which has a knock on effect on healthcare staff.

Ms Putt said: “I think the morale is down. I think we felt in the first wave there was a huge amount of support from the public and you really notice the difference working here and having that support. It's not the same as it was, this time.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMs Goodman added: “I think I'm worried that, because the vaccine is out there now, I think people are going to relax too quickly. And we can't see any end to what's going on, really. So it's the not knowing that doesn't make anything easier.”

Simon Morritt, chief executive of York Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, said staff had “stepped up without question”, taking on extra shifts, working in unfamiliar areas and cancelling annual leave with their families.

He said: “In all my years in the NHS, I have never known such intense pressure on staff, shift after shift, day after day, month after month.

“Anyone who suggests that our hospitals are quiet, empty or we have nothing to do should walk a mile in their shoes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I am acutely aware of the impact this pandemic is having on all our staff, particularly those working on the frontline and with the rollout of the vaccine programme which is moving at pace, look forward to light at the end of the tunnel.”

But that light is still a long way off.

Mr Bennett said: “I think [the public] just need reminding that people are still coming into work and risking their lives every day.

“In the last month we've definitely seen the fallout over people relaxing over Christmas and New Year. A fortnight later the numbers in hospital just skyrocketed.

“People are still dying in hospital every day. The more people abide by the rules then the less people will be admitted to hospital and the sooner it will all go away.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDr Carter added: “It’s as bad now as I’ve ever been. And the reality is that there’s many more months of this to go for the people who work in the hospitals.

“The problem for the health service is, even when Covid is over, if we ever get to that stage, there’s now an enormous backlog of urgent work that needs to be done.”